End Games of Modernity – a Convergence of crises

By Karl North | January 18, 2022

As I have written earlier in this series, modern civilization has reached an end game[1]. I am defining modernity as a form of civilization that began in the West – let’s call it EurAnglia – 500 years ago and spread in different degrees to the rest of the planet by Western imperial conquest. This essay will focus on the Western and especially US end game, with which I am most familiar. Also, the crises that I will identify are hitting harder and sooner in the West for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. To help us understand how this process may play out, I think it will be useful to keep in mind five defining characteristics of the end game and explore their multiplier effects. In overview the characteristics are:

- The depletion of natural resources signals the end of abundance

- The ascendancy of capitalist values and the cult of the individual

- Financialization engulfs and consumes the productive economy

- The end of Western hegemony

- Totalitarian solutions emerge

In this essay I will explore their interaction and likely resultant scenarios. I will argue that their convergence brings human history to an unprecedented turning point.

The end of cheap resources

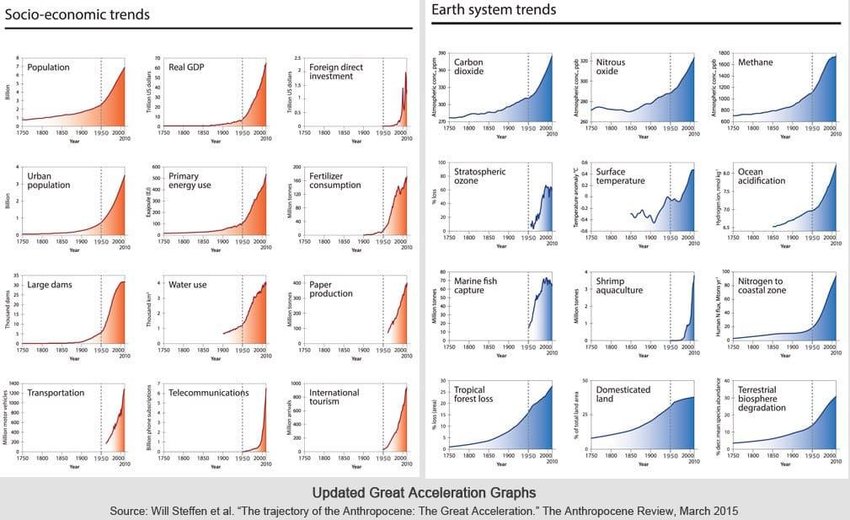

In recent times, human consumption of resources has experienced exponential growth, roughly along the line displayed in the graphs.

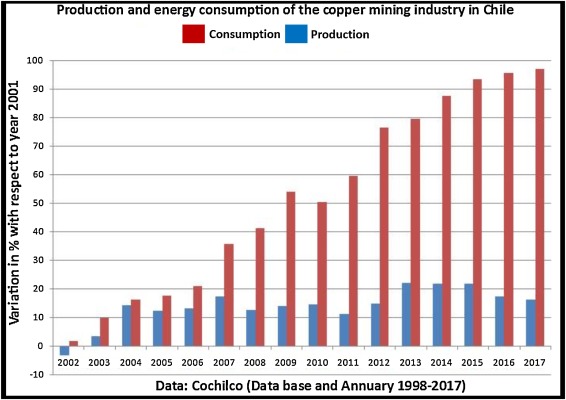

So far, the societies in the West that industrialized first have consumed the lion’s share. Hence, as resource depletion continues, the economies in Western modernity are now the first to experience shrinkage. Flush with oil, the US was the last to feel it. In the peak of net energy era of my childhood in the 1940s, gasoline was $0.25/gallon, but has always been $4-6/gallon in energy poor Europe. Now, the rising energy cost to maintain production of other resources adds to general energy depletion, as in this example for copper.[2]

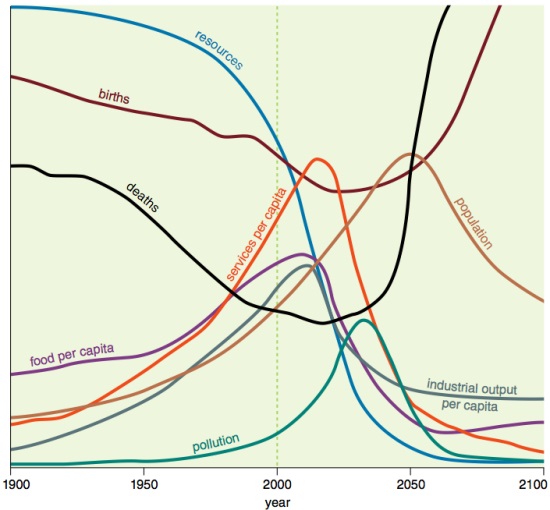

First published in 1972, the Limits to Growth world model showed how key variables change over time as erosion of the resource base occurred . Such simulation models can indicate only the general shape of change, not specific peak moments, so the time line on the graph exists only to suggest a rough time frame over which the changes will occur.

As these key variables peak and begin to fall, populations in the West, hooked on the relative prosperity that massive consumption of natural capital confers, will feel the most pain.

Capitalism and the cult of the individual

Ours has always been a social species. Hence, human society has always aimed at a balance between policies that favor the individual and those collective policies that guarantee the survival of society as a whole. As the advent of agriculture yielded a surplus above survival needs, a ruling minority appeared that had expropriated most of the surplus. Nonetheless, rulers recognized that social stability required some sort of social contract, however implicit, as in British common law, for example. Even under feudal frameworks, the peasant majority had permanent rights and the nobility had obligations to the social whole.

The rise of a capitalist class to become a ruling power over the last 500 years has brought with it a set of values that increasingly competes with the values inherent in the idea of a social contract. In its extreme expression it denies that society exists. According to the infamous formulation of Margaret Thatcher, there is no such thing as society, only individuals maximizing their self-interest.

A type of society where individual liberties trump collective goals was congenial to capitalists, who sought minimal constraints on enterprise. The Protestant Reformation gave individualism and therefore capitalism, a major boost in Western Europe. It liberated the individual from the controlling power of the Church, not only to choose an independent relationship with the deity, but also from the social and economic obligations of members of the community of the faithful to each other that Catholicism promoted.

The colonization of North America fostered a more extreme individualism for historical and geographical reasons. By 1600, a rigid social order had developed in Western Europe to deal with the scarcity of resources and their capture by privileged classes, leaving the individual little opportunity for self-improvement. Wood, the main energy source, had become so scarce as to create a firewood crisis. By contrast, North America offered a seeming endless frontier of natural capital to exploit. Moreover, more extreme versions of Protestantism escaping from persecution in Europe were prominent in early colonial America and put the stamp of their values on all later cultural development. In an apparent ‘land of opportunity’, once initial survival needs were met, everything was up for grabs. Whatever socio-economic problems that mindset generated could be ignored by moving away from them, following the western frontier. Thus, the values of self-reliance displaced the European legacy of a reliance on a communal ethic embodied in the notion of a commonwealth and the institution of the Commons.

Hence, the full flowering of an economic ethic of ‘laisser faire’, or anything goes, found its most fertile ground in what became US society. It became a cultural norm that the distribution of resources was an unrestrained dog-eat-dog competition where everyone was out for himself and ‘the devil take the hindmost’. Political conservatives were encouraged to become the guardians of laisser-faire – the police who in defense of individual liberty censured any government intervention that diminished the profits of business. Political liberals were assigned the role of upholding the illusion of government as caretaker of the common good, however poor the results. Economists, understanding their role as the ideologues of an economy where maximizing private profit trumps all other values, explained the resultant devastation of the natural resource base and the suffering of exploited classes as “externalities”.

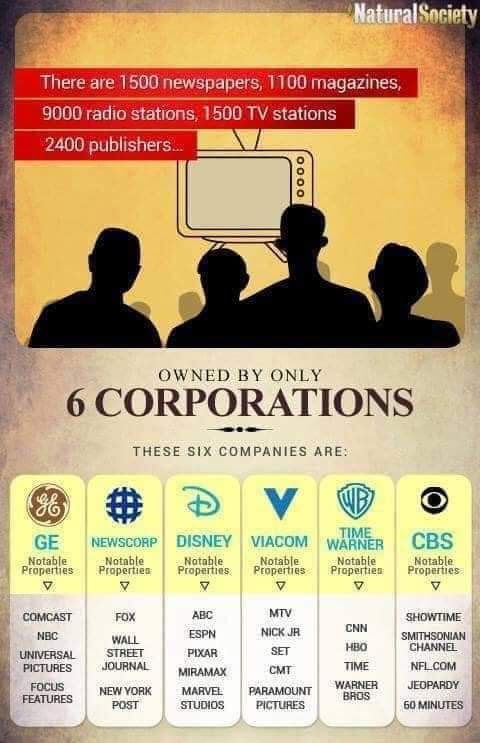

The logical result of such a well-defended system was a relatively orderly process of concentration of wealth in an ever-smaller minority class. Because this process concentrated power as well, the wealthy used that power to bend the main institutions of society to increasingly serve their interests. Government, already mainly a tool of the rich, became more so. Private control of research funding brought science under their control. As owners of the mass media and the public’s main source of information, they indoctrinated the masses with the illusion of democracy, which left the rich free to rule. Control of information allowed the manufacture of desire for goods and services, thus boosting production and profits. Discretionary consumption grew to be conspicuous among the many forms of waste generated by the system, all of course dismissed as externalities by the economic ideologues.

As the values of private profit über alles penetrate ever deeper into the body politic, the miraculous convenience of technologies, like the novocaine numbing the dentist’s drilling, keep us entranced until the inconvenient consequences downstream in time become too obvious to ignore. Some examples:

- A corrupt military-industrial cabal delivers expensive weaponry that cannot defend the country.

- Instead of health care for all, long the norm in Western Europe, in the US a big pharma cartel delivers expensive treatments that often cause more health problems than they solve.

- The junk food production system under monopoly control delivers obesity, cancer, and cardiac distress.

- Atomization of society breaks down communities.

- Social and ecological damage mounts while official narratives dismiss them as externalities.

These sorts of breakdowns will continue to accumulate as just the normal result of the system doing its thing, until perhaps communities across Western Civ become fed up, or are persuaded to accept them as the new normal. The ultimate outcome of laisser-faire playing itself out has been the gradual destruction of Western economies as their banker and corporate elites shipped whole industries out to more profitable locations.

Financialization and other foibles

The last three characteristics of modernity’s end game that I will discuss are effects of the two already described and attempts of ruling elites to deal with them. To summarize: 1) Modern industrial civilization has extracted the low hanging fruit of all resources essential to its survival. 2) The extreme penetration of laissez-faire capitalism has created an unsustainable form of civilization. Their total combined effect will be the catabolic collapse of modern societies. As this deterioration has already begun in the West, my account will focus there. Then I will consider what shadow economies and new civilizational forms might take root in the interstices of the collapse.

Aware of a collapse process that they could not prevent, Western ruling elites have devised strategies to achieve two goals:

- Keep the profits flowing to themselves as long as possible,

- Keep society from revolting in the course of its economic decline.

A partially effective pacification ploy has been the Walmartization of the economy – an avalanche of cheap consumer goods from foreign cheap labor nations financed by rising debt. Another is allowing the dilapidation of infrastructures, now many decades old – electric grid, highways, bridges, water and sewage systems –whose replacement would require tax increases that are politically toxic in an era of declining prosperity. Also, governments have systematically rigged key statistics – inflation, employment, production, etc. – to mask the shrinking economy.

Among the riskiest strategies, the one that appears likely to trigger the next bump down the economic stairway is financialization. The term refers to a progressive shift of power from corporate elites to banker elites, and a shift from an economy that produces real wealth to a speculative, casino economy.

In one sense, financialization is a normal outcome of concentration of wealth under capitalism. Bankers, as the lenders of last resort, gradually become more powerful throughout the modern age, adding risk-free brokerage fees to usury – rent producing placement of capital. However, to address the problem of sustaining consumption in an economy becoming deindustrialized, financial elites turned to fostering debt at all levels of society. The tool of choice was the Federal Reserve, which from its inception in 1913 had always been a cartel of self-serving top bankers masquerading as a monetary stabilization service of the US government. In the last twenty years, the Fed dumped cheap money at low interest rates into an economy actually in decline, creating bubbles of fake wealth in the stock and real estate markets. This enriched the financial class further while pacifying the masses by concocting a false impression of economic growth and briefly sustaining consumption. It also increased debt at all levels of society from individuals to the government, a process that could not last.

Viewed from another angle, the present combination of cheap money policy and increasing debt peonage is unprecedented in the modern age. As astute economic analysts have predicted for several years, it will lead to the mother of all financial crashes, and accelerate the current downward trend in Western economies. Of course, financial crashes have occurred before, even regularly, the last one in the Great Depression of the 1930s. They are inherent in a system that promotes unrestrained greed. And the spectacle of spreading debt has brought whole civilizations to a standstill until relieved from on high by across-the-board debt erasures, or ‘jubilees’ as they appeared in scriptural accounts of ancient times.[3] The most recent example occurred as part of the fall of the Roman Empire, and led to centuries of censure of the practice of usury – money lending at interest – by both major civilizations that arose from the ashes of the Empire – Christianity and Islam. But in the present situation there is no politically viable way out of money printing: more of it will cause hyperinflation, less of it causes interest rates on the massive debts to rise, which will make debts unpayable and crash the debt economy.

The End of Western hegemony

Because the globalized economy is closely interconnected by trade and financial ties, the coming financial crash will affect all societies. Most importantly, it will accelerate the end of Western hegemony, consisting of the US empire and its European vassals and underdeveloped colonial dependencies, and the rise, already well along, of a multi-polar world, centered around the Chinese economy, itself powered by Russian and Iranian oil.

After a 500-year hegemony in which the West saw itself as the pinnacle of progress and the US as the “exceptional” nation, the consequences we are already seeing of this unprecedented shift in dominance toward Asia are both cultural and economic.

Economic fallout

In expectation of the dollar losing its purchasing power, other nations are diminishing their dollar holdings. This signals the eventual end of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, and the end of its unfair commercial advantages and geopolitical benefits to US imperialism. China and Russia are already trading with each other and bilaterally with other nations in ways that avoid the petrodollar. For example, China is now the major consumer of Saudi and Iranian oil, much of it in direct trades. This trend sets the stage for the weakening of the dollar against other currencies, which will raise prices to US consumers of the many products the US now imports. The weakening of the dollar will add to the inflationary effect of years of financialization. And these troubles are happening at a time when decades of indoctrination to capitalist values, equating cooperation with communism, have destroyed communities as potentially viable local economies that could replace the failing national market and financial system.

The end of cheap domestic energy sources and increased reliance on foreign ones comes at a time when Western nations have been losing geopolitical control of major oil sources – Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Venezuela among others. This trend combined with the move away from the dollar will aggravate the downhill slide of Western economies.

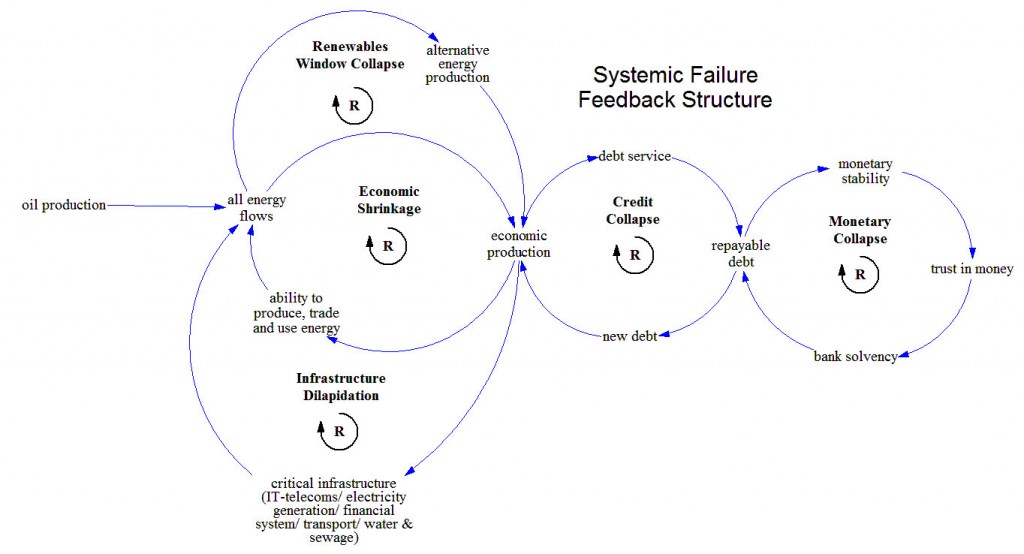

The convergence of all the end game crises that I outlined at the outset can easily trigger a cascading collapse as different feedback loops interact, as outlined in this diagram;

The convergence of crises and its implications are perceived only vaguely in Western societies, as elites have tried to disguise them in various ways. Unparalleled in our historical experience, they are bound to generate reactions that are both unique and unpredictable. How will the masses react to the acceleration of an already falling standard of living that for decades they have been led to believe would never happen? Under these conditions, how will ruling elites maintain social control?

Toward a creeping totalitarian agenda?

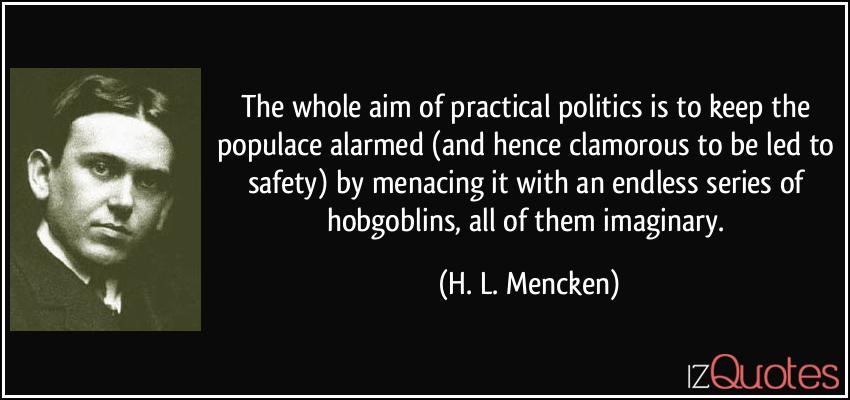

The mainstay of social control in the US has been the manufacture of consent since the rise of sophisticated advertising techniques drawing on subconscious drives, introduced early in the 20th century by Freud’s kinsman, Edward Bernays. Later, using the same techniques, Bernays added political and cultural manipulation to what had become an addiction to consumerism powered by the manufacture of desire.

The latest example of information manipulation for political and economic purposes was a psyop – a project to scare whole populations to accept a tyrannical and economically devastating set of lockdown policies and a dangerous and unneeded injection posing as a vaccine, which has reaped billions in profit to the pharmaceutical industry, all falsely justified as necessary against the spread of a virus that, for most people, posed no greater threat than a bad flu year. The policies included medical directives that contradicted empirically validated, reliable medical practices and suppressed the use of safe, effective therapies that could easily have controlled the disease. It was these policies, both medical and economic, that caused excess US deaths in the hundreds of thousands in the last two years, not the virus.

After two years, this project has revealed to astute observers the power, accumulated over decades, of the pharmaceutical industry to control by pressure or promise of benefit, a wide array of actors. This industry power enabled a small mafia of US health officials and industry billionaires to covertly create illegal genetically engineered biowarfare products – a virus and a gene therapy posing as a vaccine – and spring them on the world using a carefully orchestrated official narrative coordinated between government, mass media, internet social media platform monopolies, the research community, peer reviewed scientific journals and the vaccine industry, all delivering essentially identical messaging. The rollout of the pandemic narrative has been a spectacle of unprecedented information warfare against an unsuspecting public. The coordination and timing of the rollout reveal preparation and planning.

The unprecedented lockdown policies of the “pandemic” project achieved a secondary goal – to accelerate an already failing US economy – but deflect blame onto a virus rather than on ruling elites.

However, such an ambitious and elaborate project carries considerable risks. Incessant investigation has exposed the official narrative as a tissue of lies and forced medical authorities to backtrack on them one by one:

- In August, 2021, the WHO quietly reversed its directive for the PCR test, its primary weapon of deception in the official narrative, while allowing the false counting of Covid cases to continue until 2022 when the policy change would take effect.

- The deception that counted positive PCR results as cases of the disease was so blatant (because most of those who test positive are not sick) that medical authorities tried to cover it up by inventing a new category of Covid case – asymptomatics – people who are completely healthy but should somehow be counted as cases of Covid disease.

- The rigging of the count of hospitalizations and fatalities was finally admitted by the master of pandemic deception, Anthony Fauci himself, when he recently acknowledged the difference between cases with Covid and cases of Covid.

- Private investigation has also shown that the FDA’s language in the text of its emergency authorization of the injection carefully defines it as a “gene therapy” while falsely proclaiming it a vaccine to the public.

As the official pandemic narrative begins to lose traction with the public, ongoing economic consequences of its insane lockdown policies are combining to generate anger. Real inflation at retail for consumers has risen to around 16%, twice the official (rigged) rate, and producer inflation now at 21% promises higher future rates for consumers, even if current supply chain problems are solved.

Hence, as the convergence of crises accelerates the falling standard of living of most of the denizens of EurAnglia, elites are searching for new fear campaigns to keep order. The climate emergency scare campaign worked only on the Greta-like enviros. And another 9/11 type false flag to scare up a new foreign enemy has a poor chance to work again.

However, a society experiencing severe loss of trust in all major institutions is easy prey to totalitarian ideologies and policy solutions. The present such project of some elites is a centrally controlled digital technocracy. It is marketed as “smart technologies” that will solve all social and environmental problems. But it is so grandiose and global in scope that even if it gains some traction with the public, it will gradually spin out of control, as most totalitarian regimes have done in history.

Conclusion

Taken as a whole, the five convergent crises as they interact are unmatched in at least the last 500 years. The complexity of their ripple effects renders them unpredictable in detail in the short run, but due to resource exhaustion will at length end the industrial age. Elites appear ready to retain their privileges with authoritarian strategies.

The alternative of course is to resist in any possible way, distance oneself from mainstream institutions and economies, and build parallel structures. One can imagine it as a kind of shadow society in embryo that experiments with new civilizational forms – in expectation of the inevitable failure of totalitarian projects and the resultant disintegration and partition of large states. As elite projects experience confusion and disarray, their factional disputes will open crannies that provide opportunities for all sorts of resistance to emerge.

The irony in the situation is that the faster industrial civilization fades away the greater the suffering, but also the greater chance that a livable natural resource base will remain to support those who survive the descent.

[1] The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

End Games of Modern Civilization: false flag scare strategies and global cultural revolutions

More End Games of Modern Civilization: factional fractures in ruling elite policy

Clinging to the Titanic, or how to let go

[2] Hagens, N. J. 2020. “Economics for the future: Beyond the Superorganism”

[3] Excellent histories of financial mismanagement leading to crises of debt servitude are the works of anthropologist David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years and political economist Michael Hudson, …and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year.

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

Seasonal Greetings and State of the World

By Karl North | December 23, 2021

As the old Teutonic pagan rite approaches, we sally forth, hatchet in hand, seeking evergreens to deck the halls. O Tannenbaum! Conveniently, our mile-long track to the woodlot snakes through ten acres of clearcut logged by the previous owners in a vain attempt to cover their debts from a failed ‘back to the land’ venture. Wunderbar! Blossoming after 15 years with fragrant firs of all sizes, the clearcut is tannenbaum heaven.

So, Jane and I are still kicking, thankfully, cheerfully, albeit more slowly, still fattening a few lambs and growing a couple dozen fruits and vegetables, for us mainly, and the excess for the local food bank, and for bartering with neighbors.

Thanks to an unusual summer of rains, we enjoyed record harvests of most crops, much to the dismay of the Gretas of the world who,

unaware of the complexity of the earth system, assume that simulation modeling and its practitioners in the IPCC can predict the degree of human contribution to climate change.[1]

We are both experiencing the memory problems that come with age – difficulty dredging up words and phrases from deep memory, especially proper names, names of things and phenomena. (Jane says less with her). We each have somewhat different memory problems and can therefore help each other to trigger words and phrases otherwise lost to the archival cellar of the mind.

We are enjoying the active rural life despite increasing aches and pains, but also enjoy living in a kind of outback, on the geographical margin of the slow-moving disaster of a collapsing industrial civilization. That spectacle, however insufferable it will be for the victims, is a source of endless fascination, study and occasional writing for people like me trained and dedicated to the study of nature and its laws (systems ecology) and the study of the errant behaviors of its wholly owned subsidiary, human society (a subject sometimes known as political economy[2]). The many signs of collapse have been evident for decades, but are invisible to most people because conventional schooling provides little notion of how these complex systems work. Also, the mass media indoctrination machine constantly softens each gradual change into a new normal[3], affording an endless vista of safe spaces – hélas temporaire -

On the other hand, by now, a whole network of collapsists exists online across the planet with which I can discuss prospective scenarios, many of which I have written about for years. Unfortunately, allowed little access to the public, or disparaged as ‘chicken littles’, this network can only preach to the choir, at least when not yet censored by the Silicon Valley multi-billionaire moguls. An up-and-coming example of the genre, not yet deplatformed like many of its peers, is Titanic Lifeboat Academy.

An unusual proportion of these energy descent writers[4] are impressive polymaths, from the geologists who pioneered the warning of resource depletion, to systems ecologists and political economists, with whom I am grateful to learn. Most of the above are relatively rare in academia, because they are not made welcome. Some are good fiction writers who in my envious estimation are creating the most persuasive visions of likely futures. An example is James Kunstler’s World Made By Hand series. What follows is an attempt to put conspicuous short-term consequences of long-term collapse into some historical context.

The Decline of the West (and its Discontents)

The West claimed to be the civilization that embodied free expression. Now its censors run rampant.

The West once offered the world an example of prosperity and fairness, at least the best one available under a system of complete freedom of concentration of private capital – “A rising tide lifts all boats”. Now, the US and UK especially have become like banana republics, where a tiny obscenely rich elite exports the industrial economy to foreign shores and now presides over impoverished masses. Long ago The American Dream began to fade away.

As early as the 13th century in the Magna Carta, the West stood for the rights of individuals – to due process among others – and against dictatorship. Now after the various “patriot acts” and Corona virus decrees, anyone, including US citizens, can be held incognito in indefinite detention. Or simply be assassinated along with others on the white house extermination list.

The US proclaimed a system of government responsible to its people. Disasters of government negligence like Katrina, the Corona virus debacle, and now the grid failures across the plains states have repeatedly shown the world that its leaders don’t care for its citizens.

The West was the place where everything works. Now it is a picture of ghost towns and farm ruins in depressed rural economies and urban slums and dilapidation: the New York City subway is one of the worst in the world.

The gradual shrinkage of Western economies from global resource depletion is giving rise to a gradual increase in disorder of all sorts – military (resource wars), economic (the trap of massive debt financing and other shortsighted props), social (antifa/BLM/school shooting violence), political (Trump/Biden psychopathic governance), cultural (extreme ethnic polarization from extreme identity politics). The constituted authorities either cannot or dare not explain underlying causes, all to the increasing discredit of mainstream institutions – govt, mass media, medicine, academia – for Americans all across the political spectrum.

The dilemma of the elites[5]

Faced with a permanent decline of industrial civilization that they cannot prevent, and a narrative of endless progress with which they have indoctrinated the masses, ruling elites first sought props to give the illusion of prosperity-as-usual. An impressive one has been years of money printing to replace real wealth production, among whose consequences has been an obscenely overvalued stock market. As the crisis deepened, elites staged false flag episodes (9/11 and war on terror, Covid scamdemic) designed to scare the public into accepting increasingly tyrannical policies of social control (Patriot acts, strict media control of information, internet censorship, vax passports and mandates). One result is different forms of mass psychosis, a kind of collective hypnotism that persuades people to grasp at straws so outlandish that they would be ashamed of such behavior in normal times.

Meanwhile, our rulers are casting around for degrowth strategies, starting in the US and Western Europe – the first area to experience degrowth – a plan that will insure degrowth for us that preserves growth and prosperity for them. Evidence that at least one faction of transnational capital and national ruling elites realize the implications of inevitable degrowth and the need for an elite-orchestrated version is the “Great Reset” narrative promoted in Davos meetings of the World Economic Forum.[6] Such narratives are a marketing plan[7] that hides a more radical scheme by promoting a ‘reset’ as green, socially just and technologically cool. So far, this propaganda is aimed at political liberals who have tended to accept its implicit totalitarian aspects as a necessary ‘war economy’ (think WWII ration book). By rolling it out slowly like a slow-release drug, elites hope to avoid resistance.

The actual plan was quietly elaborated by the G7 central banker elite at its annual gathering in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and given a façade of public sponsorship as UN Agenda 2030[8]. The central hub of its many components is a scheme to solve the two looming global crises – the next financial crash and the end of the dollar as world’s reserve currency. Called Going Direct Reset[9], it resets global finance in a centrally controlled, universal digital currency, using 5G wireless to connect everyone, then uses control of money in combination with existing surveillance state technology to minutely regulate individual behavior with rewards and penalties, along the lines of the Chinese credit system. If this agenda is real and makes any headway, can it work? I address this question in the next section from my perspective as a holistic thinker.

The Great Unraveling

“The world functions in wholes; we must manage it as such, or court failure” – Alan Savory

The connectedness of the universe in which we live presents such a complexity of interactions and interdependencies that has never yielded completely to the efforts to understand and manage it.

Hence, what we call “science” has mostly retreated to laboratory conditions where reduced

interactions can generate predictable results. The trouble with that stratagem is that when the products of science are brought out into the real world and applied, albeit often in dazzling technologies, eventually all sorts of inconvenient consequences and long-term ripple effects occur. Our bodies, for example, present such complex wholes that medicine men (and women) often must resort to treating symptoms because we don’t know enough to do any better. We cover up the limitations of medical knowledge with fancy language – NSAIDs, non-steroid anti-inflammation drugs, for example, are just pain killers.

Likewise, the clusters of interacting species we call ecosystems and human societies are complex wholes that pose stumbling blocks to understanding how they work, and therefore to management efforts. Students of complexity observe that throughout history, elaborate attempts to shape whole societies eventually break down as events spin out of control. Apparently robust social constructs like the Roman Empire ultimately collapsed in chaos and disorder.

Applying the revelations of complexity science and its understanding of the limits of the advancement of knowledge, what can we say about the prospects of the extravagant plan of global private capital to address the breakdown of industrial civilization with a central banker controlled digital technocracy?

Many big picture thinkers like Catherine Austin Fitts, longtime relocalization advocates like myself, share my view, voiced in Who’s Afraid of the Great Reset? Fitts says the blueprint of the international banker elite is going to be too complicated, too outside the laws of nature, but extremely messy (think Iraq ever since the attempt at US subjugation began in the first Gulf War), and will therefore fail, perhaps not for the lack of trying. Fitts says (and I agree) that people should face this unprecedented situation squarely, and begin to build a relocalized economy, a parallel economy from the bottom up.

What is the evidence that the Great Reset will fail? First, regarding failures of such grandiose schemes, there are a lot to choose from. Consider the track record of the CIA, tasked, as agent of elite interests residing inside the US government, with interference in other nations, interventions that had to be clandestine because they violated international law, the UN Charter, and the US Constitution and proclaimed US ideals of foreign relations. Most of its so-called color revolutions either failed outright or turned the victim nations into economic, political and ethnic disasters. The list is long – Russia in the 1990s, the former Yugoslavia, the former Ukraine, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, Venezuela, and most recently Belarus, one that failed to even get off the ground. And yet the CIA is supposed to be the main US source of intelligence about world affairs.

Closer to home, another example of a power elite scheme going awry began with the attempt, starting already in the 2016 election campaign, to remove by fraudulent means the elected Trump administration. First, it fueled the existing standard divide-and-rule political polarization strategy by making the mass media into the attack dog of the Democratic Party. The result was a mass media that dropped all pretense of journalistic neutrality and became deeply discredited among political conservatives already prone to criticize it as a tool of liberalism.

Then, when medical authorities rolled out the ‘pandemic of fear’ narrative (whose crimes under the direction of Anthony Fauci[10] I have detailed elsewhere), the conservative pole, half the electorate, no longer disposed to believe anything coming from the mass media, was effectively immunized as it were, against the official pandemic narrative trumpeted from Washington and amplified faithfully by the mass media from CNN to NPR.

The result, ironically, was that conservatives, which liberals often disparaged as gullible, redneck illiterates, began to question the official pandemic story while liberals, now habituated to trusting the media as a political ally, bought the story without question. Courageous scientists and medical professionals, aware of the science-free nature of most of the policies decreed by corrupt government medical authorities, organized to fight back[11], but were allowed no access to the public via the mass media. When medical professionals were forced to turn to politically conservative websites and media platforms to expose the official narrative and to reveal cheap and effective therapies that can control Covid 19 as no worse than a bad flu year, conservatives actually became more knowledgeable about the virus and the real nature of the ‘pandemic’ than most liberals. Thus, when the Biden administration and European governments made the fatal mistake of trying to impose a vax mandate, a vigorous resistance took form.

Some critics claim that the goal of the pandemic policies was never merely to generate obscene profits in the pharmaceutical industry, but rather to generate fear of a supposed medical crisis as justification for imposing the next step in a process of habituating Western societies to a totalitarian order. If this were the goal, an open-ended vax mandate certainly fits into the plan. Discovery that what first looked like a botched response to a new virus has become an issue of individual freedom and human rights has caused a violent reaction in Europe, with mass protests occurring over many months. Indeed, the whole official pandemic narrative is unravelling in many directions[12]. Those who still can’t see it happening will no doubt have the opportunity in the near future. Thus, once again, a grandiose scheme of the powerful has encountered the unpredictable nature of our complex universe.

International Speakers Address Rallies in Europe Against the Global War on Freedom, in Medical Disguise

On November 12th and 13th 2021, experts from around the world attended rallies and press conferences in Switzerland and Italy, to support the worldwide resistance against the global war on freedom and democracy.

Blessed are the peasants….

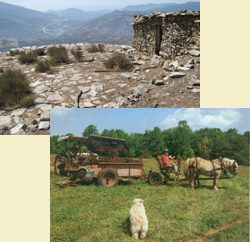

…for they shall inherit the earth. Ignored by elites as remnants of a primitive past, peasants, over fifty percent of humanity by some counts, represent a chance for survival of the species as industrial economies, costly luxuries of the fossil fuel age, gradually fade away. I have explored the potential of this scenario in “The quality of peasant life: a scenario for survival” and “The peasants shall inherit the earth”, as an option to explore by younger generations who might be looking for ways to navigate the energy descent.

Afterthoughts

I am grateful for having lived an incredibly full and exciting life by my rather strict and unusual standards, and enjoy memories of almost all of it, despite the stresses occasioned by constantly having to adapt to the conditions of life in each novel adventure that we embarked on. We engaged deeply with other cultures and worked with people in many places – Geneva, Paris, New York, Bamako, Havana, a Zapatista rebel village in Chiapas, six years in this mountain village in the Catalan Pyrenees:

Most of these locations were at the top of their game at the time we encountered them, but not so much now, according to reports. So, the global tourism that appeals to many retirees is not a temptation. I, for one, am content to live with excellent memories. Here is one from our farm in upstate NY, caught at full gallop by a farm apprentice, the intrepid cameraman Brian McKay, circa 1995, replete with sleighbells ringing.

And another, five years later, after horses and driver had aged to a more sedate trot.

With such adventures to look back on, I can safely say that I have achieved most of my great expectations, however strange they may seem to the average person.

May your new year be as satisfying as the last,

Karl

[1] Faced with the vast complexity of the earth-sun system, with all its cycles of variable time frame (such as solar maxima and minima, ice ages, etc.) and feedback loops, many unknown, most experienced practitioners in using the method are saying there is no way that system dynamics simulation modeling can show to what extent emissions from fossil fuel use are a significant factor in climate behavior. Sure, we can prove tiny pieces of the puzzle like the causal relation between fossil fuel burning and greenhouse gas production, but so what? Water vapor is a far more potent greenhouse gas, is constantly changing, and has very different effects in different layers of the atmosphere. There is enough complexity in that one variable alone to give one pause.

[2] Political economy is an approach to the study of human society grounded in an understanding of its power structure – including its locus and concentrations and its means and avenues of execution in end point decision making.

[3] See, for example, the latest by C J Hopkins, The Year of the New Normal Fascist

[4] An early example is The Limits to Growth project, originally published in 1972.

[5] See my End Games of Modern Civilization: false flag scare strategies and global cultural revolutions

for a more detailed view.

[6] https://www.weforum.org/great-reset,

[7] Agenda 2030/Great Reset marketing video for dummies – 8 predictions for the world in 2030

[8] Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

[9] https://home.solari.com/coming-thursday-2020-annual-wrap-up-theme-the-going-direct-reset-the-central-bankers-make-their-move/

[10] For the whole chilling story, see Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s just published The Real Anthony Fauci; Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health. If you’ve been buying the official Covid party line and scare campaign; the first 100 pages alone will knock your socks off. Most of the revelations have long been available in online alternative news sites, but Kennedy is the first to break through mass media censorship.

[11] https://americasfrontlinedoctors.org/, German Corona Investigative Committee,

https://covid19criticalcare.com/covid-19-protocols/math-plus-protocol/

[12] https://doctors4covidethics.org/

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

More End Games of Modern Civilization: factional fractures in ruling elite policy

By Karl North | December 16, 2021

Historical studies of civilizational collapse reveal a pattern that occurs at some point in the collapse process[1] – ruling elites begin to lose control, and policy disagreements arise. In this essay I will explore evidence that faultlines in pre-existing factions in the US ruling elite, once kept in the background, are emerging into the public view as conflicting policy choices across diverse areas of governance.

First, I will summarize key signposts of collapse and drivers of revolt that have elites concerned to the point of disagreement over policies of social control, as follows:

1. In August 2019, in a financial environment where the prime rate is near zero, the overnight loan rate, essential to keep global dollar transactions flowing, shot up to 10%. To meet this crisis, the Fed had to begin constantly dumping large amounts of new money (actually debt – formerly known as quantitative easing) into the money supply, and has been quietly doing so ever since. This can have only two outcomes. Because the money creation has far outstripped the production of real wealth, debts based on it will ultimately default, crashing the global economy starting in the Western world, the most highly leveraged economy. Or, money creation will eventually cause hyperinflation, thus reducing everyone’s bank account to zero.

2. A looming energy shortage has been forestalled by tight oil production, which temporarily made the US the swing producer and granting some control over oil price. US shale never grossed over $700 billion for about $1 trillion investment, so the nonviability of the industry at an oil price that allows the industrial economy to survive is now evident to ruling elites. The cost of oil has doubled in the last year to over $80/bbl (as of October 2021) despite an already depressed US economy, and will continue upward until it collapses the economy sufficiently to depress demand and price. Price depression will briefly revive the economy slightly, causing another price rise. This fluctuation will continue, each time causing wave of permanent shrinkage in the economy.

3. To meet the looming energy shortage, global elites have played a virus (whether intentionally so designed or not) in a way to shut down parts of the Western economies to bring energy consumption in line with declining production. Despite sharply different policies – say, in Sweden vs UK – the results have been similar across Europe, and apart from some specific complications, the overall death rates from the virus itself not significantly higher than the normal flu season. Hence, the “media pandemic” story is no longer viable (especially in Europe, less among the more submissive US population). The “dangerous new variant story” is not working well, so unless rulers can invent a new disaster, the coming energy shortage and the acceleration of the collapse process will make itself felt in many ways, and the path is clear toward hyperinflation and revolt. In the US, the Democratic Party has been used to weaponize the pandemic narrative to destroy the Trump presidential campaign.

4. “The Great Reset” is a way of getting people ready for hyperinflation that will wipe out current levels of production and consumption. Digital currency makes redenomination of currency easy. It facilitates control of prices and income, replacing lost income with a food stamp type of guaranteed minimum income in what becomes an austere, low-level economy. Combined with the existing surveillance technology, a digital currency paves the way for the roll out of a totalitarian state, which will be necessary to conserve diminishing resources and reallocate them to sustain an affluent elite and their managerial minions .

5. The digital revolution has made people docile and heavily reliant on their smart phones. Cut off the internet, or simply censor its alternate sources of information (as is now occurring), and people are helpless.

In reaction to this situation, ruling elites have split into factions promoting different policies in the following areas: foreign policy, the pandemic story, the use of political parties as a tool of divide-and-rule polarization, and the resource depletion that is bringing industrial civilization to a halt.

Foreign Policy

Suddenly, with the arrival of the Biden administration, signs are appearing that at least one faction of the ruling elites is reconsidering its aggressive foreign policy of hybrid war against Russia. One of the reasons is obviously a matter of domestic politics – the desire to take down the Trump presidency with a range of fraudulent claims linking Trump to Russian influence was no longer necessary. But a potentially more important reason is that hybrid war all along the border of the Russian federation (including its soft Islamic underbelly) has not been working well, and even backfiring. Here are some of its failures:

1. CIA color revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine using political extremists as a spearhead created regimes led by corrupt oligarchs (and in the Ukraine a neo-Nazi police state) who persecuted Russian populations in these former Soviet republics. Those populations declared independence and, with help from Russia, defeated Western supported attempts at reconquest, leaving those states in a mess that is an embarrassment to their Western backers. Attempts at color revolution in Belarus and Venezuela have failed at the outset.

2. The US invasion and occupation under cover of a Western “coalition of the willing” of Afghanistan and Iraq, and Syria, Libya and Somalia using Islamic extremist mercenary proxies, never achieved its goals of imperial control, and left partially destroyed, failing states. The official acknowledgement of defeat in Afghanistan and the ignominious retreat at the eleventh hour is but the latest in a long string of failures that have emboldened nations subject to US imperial control to reassert sovereignty. Another result is Arab hatred of the West that is leading even the medieval monarchies in the region who were reliant on US protection to reconsider that relationship.

3. The rise of a sovereigntist group of oligarchs in Russia led by V. Putin stalled the penetration of Russia by transnational capital that had been partly achieved in the decade of the 1990s. The “sanctions” strategy of economic warfare not only failed, but backfired as Russia seized on the opportunity to rebuild its domestic economy and strengthen its sovereignty. Moreover, Russia’s totally state controlled military industrial complex has achieved technological superiority (at one tenth the cost) over a US one that corruption and private control has reduced to a capitalist cash cow. The result, as the Pentagon admitted in its report to Congress, is that the US can no longer fight a major war.

A number of geopolitical analysts are describing the Putin-Biden summit, leading to a joint statement on strategic stability on June 16th, 2021 as the acknowledgement of the above regional defeats, a new configuration of power in the region, and thus the emergence to predominance of a ‘faction of caution’ (see here, here, here, and here). Thus, according to geopolitical military analyst The Saker,

Yet, what Biden did and said was quite clearly very deliberate and prepared. This is not the case of a senile President losing his focus and just spewing (defeatist) nonsense. Therefore, we must conclude that there are also those in the current US (real) power configuration who decided that Biden must follow a new, different, course or, at the very least, change rhetoric. I don’t know who/what this segment of the US power configuration is, but I submit that something has happened which forced at least a part of the US ruling class to decide that Obama’s war on Russia had failed and that a different approach was needed. At least that is the optimistic view.

Hence the request of a face-saving summit served to acknowledge all this and back off, at least for a while.

However, many continuing US contradictory words and actions against Russia and its geopolitical interests reveal that the faction fight inside transnational ruling elites is not in remission. Why did Biden personally attack the Russian president just before the summit, if he truly wanted more stable relations? Why the provocation of sending a warship into Russian waters off Crimea? Why two new US air strikes in Syria and Iraq recently – acts of war according to international law? Why did the deep state’s attack dogs in the US mainstream media denounce Biden’s diplomatic change of tone in the summit? International investigative journalist Maram Susli has revealed $350 million in Pentagon contracts to US companies to buy Eastern European made weapons, which cannot be used by US troops, just as PBS Frontline brought Al Qaeda terrorist head Al-Joulani on its show to give him a makeover as leader of the “good guys”. Is this all just for domestic consumption as The Saker suggests, or is it evidence of the hegemonist faction angling to retain skin in the game? Obedient to their deep state coaches, many in the mass media have crucified the Biden administration for the decision to end the war and occupation of Afghanistan. Now even Democratic Party leaders are calling for a package of sweeping new sanctions against Russia that undermines the spirit of improving relations that Biden attempted at the Geneva summit with Putin.

On the other hand, the US appears to have given up completely on its Ukraine color revolution, which has become a Nazi-occupied economic and political disaster. The coup de grace was to dump the Ukrainian debacle on Germany in a deal that included some vague German commitments to Ukrainian reconstruction.

Finally, a multitude of domestic crises and an increasingly polarized and contentious domestic population may be shifting Washington’s attention away from foreign hegemonist programs to suppression of domestic revolt.

Extreme polarization of party politics

For millennia, elites have successfully used the strategy of divide-and-rule to control their societies. In the modern age Western elites have accomplished this by creating a stage show they call “democracy” in which different political parties compete for the allegiance of the electorate with programs claiming to serve the public interest, but which rarely stop them from serving the interests of the ruling class, which is the main function of government.

In the US today, ruling elites seeking to divert attention from their role in collapse have encouraged the two parties to engage in such extreme measures against each other that they are gradually discrediting themselves into political impotence. One might ask: What good is a stage show that no longer fools anyone? In any case, the occasion for this more radical strategy was the appearance of a loose cannon presidential candidate, one who recognized that he could win by voicing verities and countering official narratives in a way that no president had done since John F. Kennedy:

- He denounced the serial wars, so lucrative to a corrupt military industrial complex and its investors, as failures that served no national security purpose, and called for the repatriation of the troops.

- He called for Europeans to shoulder the costs of NATO, the cover for US military occupation of its Western European vassal nations, which in effect questioned its very purpose.

- He denounced the progressive deindustrialization that ruling elites had carried out by moving their investment to cheap labor regions of the world, leaving impoverished a large population that became known as “the former middle class”, and called for a return of the nation to industrial greatness.

Deep state agents of the ruling class easily prevented the politically inexperienced president from achieving any of his program, but the rhetorical damage he caused to the official narrative endangered the social order and had to be neutralized. The chosen instruments were the Democratic Party, which in an election year was happy to oblige, in alliance with a corporate controlled mass media that gave up any pretense of journalistic integrity. Assisted by agents of the deep state, these institutions launched a campaign to destroy an elected sitting president by any means, however fraudulent and even treasonous, as it turned out.

What ensued? First, a campaign of identity politics starring BLM/Antifa attacks on police in cities across the nation, weaponized by corporate funds and supported by Dem Party mayors and governors, causing violence that destroyed whole neighborhoods, which the mass media called “peaceful demonstrations”.

The second part of the campaign to neutralize the Trump administration, again embraced by the Democratic Party, was an attempt to link it to alleged Russian interference in US politics, now exposed as fraudulent and involving the intel establishment and the FBI in criminal activity.

The third part of the campaign was to elevate a manageable virus into a purported pandemic, again heartily embraced by the Democratic Party. The official pandemic narrative, long subjected to massive protest in Europe, is now unravelling even in the US, further discrediting the Democratic Party.

The results?

- A demoralized and dysfunctional police leading to growing crime across the nation.

- A further discrediting of the Democratic Party among lower income populations whose neighborhoods were trashed by BLM/Antifa violence, and whose livelihood suffered under pandemic lockdown policies.

- A mass media who achieved further discredit to itself by dismissing all who objected to the campaign of violence as white male supremacists, by constantly broadcasting false Covid 19 case and fatality counts, and by suppressing and denouncing virus treatments proven to reduce the disease to below pandemic status.

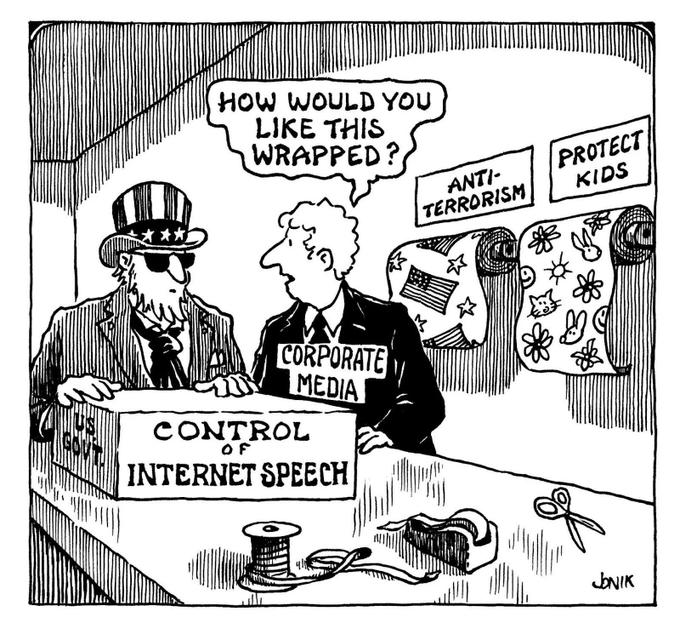

- A campaign to censor free speech, orchestrated by Silicon Valley billionaires, in one of the few places it still exists – on the internet.

The above list is far from complete, but must give pause to ruling elites as they see the very institutions, they count on to maintain the social order losing credibility and traction.

Revolt against the pandemic story and its lockdown agenda

Thousands of courageous medical professionals around the world[2] have united in organizations to expose the lies in the Covid narrative, as follows:

1. All the cheap therapies banned by authorities in the West and especially in the US, but used effectively in thirty other countries[3] have been proven to prevent or reduce the disease to a situation far less perilous than a pandemic, when used in a timely fashion. Despite the lies from the authorities and media, the therapies are completely safe and have been used effectively on many health problems for many decades. Used as both a preventive and a therapy in various cocktails, these cheap treatments almost eliminate the need for hospitalization in the very small at-risk population that can get sick from infection.

2. This virus does not, and did not cause a pandemic. Deliberate exaggeration of case counts using a test that as used in many countries according to WHO instructions generates at least 50% false positives. Although the test cannot diagnose disease, medical authorities such as Johns Hopkins are feeding the results to the media as counts of cases of Covid 19 disease. These greatly inflated case counts are used to scare and deceive the public. Moreover, fatality counts are rigged to count deaths by all sorts of causes. Most people under seventy infected or not, do not get sick, or get an easily treated mild version. Medical authorities like Fauci, CDC, NIH and WHO quietly admit that fatalities are no greater than the annual flu season, contradicting the scare message that they are trumpeting to the media. The official suppression of effective treatments and a media campaign to falsely claim that a vaccine is the only solution did cause a medical crisis, mainly in countries like the US with a large low-income at-risk population who get poor health care. NYC with its large population of inner-city poor thus becomes a hot spot, magnified in the media to scare the whole nation. These hot spot crises occur every year in the flu season due to poor health care systems.

3. In these ways authorities have stampeded the public into accepting draconian lockdown policies that are not only unnecessary but cause more suffering than the virus. Most of the lockdown policies have proven not only ineffective, but are not necessary, given all of the above. The collateral damage of the lockdown policies has caused more suffering than the virus.

4. The so-called vaccine available in the West is not a vaccine, it is a gene therapy. A long string of US patents over twenty years reveals the creation, mostly in US research laboratories, of a genetically engineered virus, not a natural mutation of a virus from an animal like a bat or a pangolin. In tandem with this virus, patents divulge the creation of a customized designer “vaccine”, This experimental, high-risk product that authorities and media are trying to scare everyone into injecting is totally unnecessary, given all of the above revelations. Moreover, the injection is producing adverse events that are orders of magnitude above those of any previous vaccine. Peer reviewed studies of its use in highly injected populations like Israel and the United Kingdom disclose a pattern of recurrence of the disease among the injected, which shows 1) that it was never designed to confer immunity, unlike a real vaccination, and 2) that booster shots don’t provide immunity either.

The above-described revelations are percolating into the collective consciousness, especially in Europe, despite almost complete suppression in the corporate media, censorship in the alternate online media and harsh condemnation of critics of the official “pandemic” narrative. In the US, the pandemic story has lost more credibility in politically conservative populations, partly because liberals politicized the issue by embracing the official narrative aggressively as a way to destroy the Trump administration. Attempts by authorities to pressure people into accepting injections, and stigmatizing the “unvaxxed” and punishing them with “vaccine passport” requirements have sparked references to parallels with the classification in Nazi Germany of a whole class of society as subhuman “Untermenschen”, and polarized society further.

As awareness spread of the false rationale for most of the elements of the lockdown policies, authorities began flipflopping in their support for the most unpopular, such as mask wearing, keeping social distance, and quarantining school children at home, thus suggesting a split in the ruling elites as to how to continue the “pandemic” as a scare campaign. The New York Times, after spreading the “pandemic of fear”[4] official policy narrative as certainties for over a year, is now running cover stories such as “Covid is a Mystery”, admitting sotto voce that most of those certainties may be untrue. The WHO has now admitted that its directive to use the PCR test – which became the tool for the scare campaign – was a mistake. The profit motives of the vaccine industry require fear mongering, but some authorities may be regarding the growing polarization and revolt as self-defeating. The Democratic Party and most political liberals, having embraced the pandemic story now unravelling as mass deception and lockdown policies now exposed as ineffective, are now saddled with a failing fear campaign.

Hence, as the fall 2021 college football season heats up, evidence appears among the young that the Covid scare story is unravelling in places and holding strong in others. In schools around the country, especially big ten schools, lockdown protocols are lax and stadiums are packed with maskless fans. In others, like SUNY Binghamton for example, injection is the rule if you want to go to school, and masks are required in classrooms. This is evidence in the college generation of how polarized and politicized the pandemic narrative has become. The fact that deep state controlled mass media like the New York Times are reporting on the mounting opposition to lockdown protocols suggests concern in at least some quarters of the ruling class that the Covid gambit may have been overplayed and that political polarization is getting out of hand..

Resource Depletion

Underlying all the convergent crises and attempted solutions already discussed is global resource depletion and its symptom – the long-term growth in the cost of everything as long as business continues as usual. Hence, elites are planning degrowth for us that preserves growth and prosperity for them. Evidence that at least one faction of transnational capital and national ruling elites realize the implications of inevitable degrowth and the need for an elite-orchestrated version is the “Great reset” narratives promoted in Davos meetings of the World Economic Forum. These narratives hide technocratic totalitarian degrowth plans behind propaganda that promotes the ‘reset’ as green and socially just. So far, this propaganda is aimed at political liberals who have tended to accept the totalitarian aspects as a necessary ‘war economy’. Conservatives, suspicious of anything promoted as liberal, are actually more sensitive to the ‘big government’/fascist nature of elite plans.

[1] See Dmitry Orlov’s Five Stages of Collapse

[2] https://covid19criticalcare.com/covid-19-protocols/math-plus-protocol/

https://covid19criticalcare.com/covid-19-protocols/i-mask-plus-protocol/

German Corona Investigative Committee

[3] https://americasfrontlinedoctors.org/

[4] https://de.rt.com/international/128471-yale-epidemiologe-corona-krise-ist-von-behoerden-erzeugte-pandemie-der-angst/

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

Who’s Afraid of the Great Reset?

By Karl North | November 6, 2021

In a recent piece I said, “Great Reset narratives reveal that transnational capital and national ruling elites realize the implications of degrowth. Hence, they are planning degrowth for us that preserves growth and prosperity for them.” Because their agenda calls for a major systemic shift in resource allocation, a centralized digital currency and other draconian policies that will be obvious to everyone, I see a number of reasons why such attempts could fail.

The limits of managing complexity

From the beginning of the scientific age in the 17th century, scientists found that achieving predictable results of experiments in the real world was impossible because the variable they wished to understand is usually emmeshed in a complex of causal relations.

So, they retreated to laboratory conditions where they could reduce the variables in play to manageable few. When even minor changes in complex systems like global society yield inevitable unexpected consequences (for example the many fizzled CIA-orchestrated color revolutions), major ones are likely to spin out of control in many directions. This is the predicament that attempts at systemic-level change agendas like The Great Reset plan cannot avoid.

False flags no longer work

As for the false flag scare campaigns they need to compel submission to a top-down system revolution, elites have worn out their usual options. The Mideast wars were profitable, but never popular, and the Islamic threat is less likely to work a second time.

The pandemic narrative did scare a lot of people into blind obedience because the threat it fabricated was a domestic one, but daily experience with “the virus” and its “solutions” is gradually exposing the lies of the official pandemic narrative. Like your three-week old bottle of milk, the covid campaign of fear and tyranny has passed its sell-by date, which its creators may not have thought through. People are beginning to smell a rat, or simply get tired of all the social shackles. Accelerating the unraveling of the official pandemic narrative are two powerful videos, Plandemic Part 1, the most viewed and banned documentary of all time, featuring Dr. Judith A. Mikovits, one of the leading medical professionals who are fighting back against the official covid narrative, and Plandemic 2/Indoctornation, with David Martin, a leading investigator of corruption in high places, which thoroughly documents the criminality that the covid phenomenon has exposed in the medical industrial establishment.[1]

China bashing is all noise

Constantly amplifying Washington imperial propaganda for years, the mass media have built up a reservoir of hostility toward China and Russia. But the latter, having great success simply waiting as the West self-destructs, are content to be patient and roll with the rhetorical punches and sabre rattling thrown their way. After years of failure to provoke aggressive behavior from Russia and China, the threat of foreign aggression is wearing thin in the Western world. And the US military is in such bad shape (as its high command is well aware) that a US attack on the sovereign territory of these nuclear powers is out of the question.

The clock is ticking

It may be too late for an elaborate reset plan to succeed. Several simultaneous deepening crises are each reinforcing the others and reaching tipping points in a global economy that unrestrained profit-seeking has pushed to the limits of fragility. The money printing and debt financing that is artificially keeping the system going has reached an end point where its ultimate negative consequences are now appearing. Meanwhile the economic damage that the covid caper created is still unfolding. Oil geologists say that the world is close to the point where energy production can no longer keep up with consumption; hence, the economic drag of resource depletion is becoming so visible that it cannot be ignored. The combined effect on domestic economic security – inflation, unemployment and supply chain failures – is building social unrest within nation states: waves of strikes and sick-outs, regular demonstrations in Europe against tyrannical policies, signs of sectoral and local rejection of central government policies, and individuals simply opting out of the system.

The explosion of counter narratives

Over the last few decades, the US mass media have been consolidated into a pyramid controlled from the top by a small cartel of corporations like CNN and NBC, themselves controlled by a few global investment corporations like Blackrock and Vanguard.[2] Because of monopoly control, different media could no longer scoop each other with the results of investigative journalism; thus the media cartel was able to deliver the same narrative throughout the media pyramid – a set of daily messages whose content serves the political interests of its class owners in the transnational elite. And from the beginning of the digital age, the dominant internet media platforms like Facebook and YouTube have been under monopoly control of digital technology billionaires.

However, growing awareness that the mass media is openly serving the political propaganda interests of its owners has discredited it as a source of reliable news, and stimulated a search for independent sources. On the internet, the growth of economical alternative media platforms to replace the Silicon Valley monopolies is rapidly spreading independent information sources and narratives that are eroding the credibility of all major societal institutions and their policies, not just mass media.[3] And the elites cannot easily shut down the internet – their power and profits depend on its existence.

In sum, any grandiose system restructuring that transnational elites are trying will likely be complicated by uncontrollable unrest within nation states. Short of declaring global dictatorship, what is a desperate ruling elite to do?

[1] https://sovren.media/video/plandemic-part-1-20.html

https://plandemicseries.com/plandemic-english-subtitles/

[2] See the well documented video documentary Monopoly: Who Owns the World

https://rumble.com/vmyx1n-monopoly-who-owns-the-world-documentary-by-tim-gielen.html

[3] Examples are https://www.peakprosperity.com/ and https://titaniclifeboatacademy.org/

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

What props up the delusion of growth paradigm?

By Karl North | September 19, 2021

The general trend in the global economy has been toward lower growth and productivity in the last half century. This trend is easily explained in biophysical economics as due to 1) increasing scarcity of finite resources due to depletion, itself the result of massive consumption in the modern age, and 2) erosion of carrying capacity due to many types of ecological damage from the era of massive consumption of natural resources. Conventional economists have nothing in their economic worldview to explain the trend, so they hide their failure with jargon words like ‘stagflation’ or ‘secular stagnation’, which don’t explain anything.

Faced with a trend, critical to the future of industrial society, that they cannot explain, economists have offered solutions that naturally don’t work, but appear to perpetuate growth by artificial means. A solid literature has developed to expose these solutions as illusory. This essay will summarize some of its conclusions, which may be particularly useful to those who may have been inclined to believe the illusions propagated by governments and the mass media.

Debt-based growth

Money printing, hiding under labels like bailouts of too-big-to-fail central banks and quantitative easing, which started with the financial crisis of 2008, accelerated recently as a policy response of a fabricated “pandemic”[1]. The policy response did habituate the public to house arrest under false pretenses and other violations of the Bill of Rights.

But money printing produced little growth in the US except briefly in economically nonviable enterprises like extraction of unconventional oil, or in the weapons economy where a decades-long fear campaign has sustained a bloated defense budget while driving the US government deeper into debt. Otherwise, the main effect has been to create dangerous bubbles in the rentier economy (an oxymoron), which consists primarily of the stock market, including speculative markets like currency and derivatives, and real estate. This process will continue until an inevitable crash brings about a new era of austerity.

Rigged statistics

Key government statistics like unemployment, inflation and gross domestic production (GDP) that mass media have taught the public to rely on as measures of the health of the economy have been defined in a way that deceives. This deception has been exposed in efforts like Shadowstats that have revealed unemployment and inflation that is relevant to the prosperity of most people to be 2-5 times greater than in government statistics. GDP includes bubble “production” in the rentier economy and derivatives, none of which measure growth in real wealth. Thus, GDP is useful to the investor class but has misled the public as an assessment of most people’s standard of living despite how it is represented in the mass media and government. The success of rigged statistics is declining along with credibility in all mainstream institutions.

Energy alternatives

Along with many others, elsewhere[2] I have argued the impossibility of building energy alternatives to a scale that would support an industrial society. However, to summarize:

- The energy return on energy invested (EROEI) of alternatives is too low to sustain industrial economies.

- Even if it were possible to significantly replace fossil fuels with other energy sources, that would perpetuate the industrial economy and its resource depletion, eventually bringing down the industrial economy.

- The cost of conversion of the economy and infrastructure to new sources of energy itself entails sacrifices that 1) the global economy in its present decline can no longer afford, and 2) that already impoverished masses could not survive.

For now, the official narrative of endless growth continues to persuade most of the public that some sort of energy will be available to sustain industrial society. Different subnarratives are promoted according to political persuasion. Liberals have been induced see planetary overshoot mostly in terms of climate change, and so tend to support energy alternatives. Conservatives have been convinced to distrust government plans, and so tend to count on private enterprise to deliver more oil. Some Western transnational elites appear to understand the resource depletion problem, hence are promoting a “great reset” (see a discussion of this phenomenon below).

Technocratic solutions

“Great reset” narratives reveal that transnational capital and national ruling elites realize the implications of degrowth. Hence, they are planning degrowth for us that preserves growth and prosperity for them. These narratives hide technocratic totalitarian degrowth plans behind propaganda that promotes the ‘reset’ as green and socially just. So far, this propaganda is aimed at political liberals who have tended to accept the totalitarian aspects as a necessary ‘war economy’. Conservatives, suspicious of anything promoted as liberal, are actually more sensitive to the ‘big government’/fascist nature of elite plans.

Conclusion

At this juncture, some stories of the official narrative are becoming increasingly discredited in some quarters of society, while the delusions are holding well in others. And original delusions are often replaced by equally illusory subnarratives. It should be remembered that the core narrative that veils the concentration of wealth and power in a transnational financial elite has penetrated Western culture for over a century, passed down from one generation to the next, and is therefore deeply embedded. At this point it is therefore an open question when the dominant social order will crumble, and what will replace it.

[1] https://www.unz.com/proberts/how-the-covid-pandemic-was-orchestrated/

[2] Energy and Sustainability in Late Modern Society (http://karlnorth.com/?p=1244)

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Recent Additions, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

End Games of Modern Civilization: false flag scare strategies and global cultural revolutions

By Karl North | May 10, 2021

Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it… – Santayana

…First as tragedy, then as farce. – Karl Marx

Modern civilization is an interactive and interdependent whole that ties together, however loosely, specific energy drivers, technologies, physical and social structures, ways of living and cultural beliefs and values. Elements distinctive of this whole are fossil energy sources, energy intensive technologies, large urban centers that feed on rural peripheries, global political economies, a reductionist way of knowing and related worldview and belief/value systems. As this whole begins to disappear and be replaced by other forms of civilization, those who hope to navigate this process need the holistic perspective to identify its end games and how to circumvent them.[1] This essay will describe key end games currently in progress, their interdependency and trajectory.

Because things in a whole hang together, most everything in modern civilization, because it is driven ultimately by energy and natural resource depletion, is entering or will enter an end game, although in local variations at different times, places and rates. For most people, the reigning worldview of endless resources and growth will obscure the dead-end nature of these processes until late in the game.

The Marxian caution to view the present as history appears to gain the least traction in the US. Here, history tends to reduce in the collective consciousness to what happened last week. No amount of exposé of last week’s bundle of lies in the corporate controlled media seems to cure Americans of the habit of acceptance of this week’s media stories as depictions of the real world. With that understanding, some of the end games and their historical antecedents recounted below may come as less of a surprise.

Resources

Oil is essential to run an industrial economy because it has functions – as in transportation – that are not replaceable with other energy sources in an affordable way. Momentarily, the use of cheap credit to spawn economically nonviable tight oil production in North America has disguised the decline of most planetary oil production. That “fracking” and tar sands game is now ending.