« The Achilles Heel of the Climate Change Warriors: The limits of complexity science | Home | Stories of my Life: A Swiss Scavenger Hunt »

Watering the Garrotxes: donkey farming in the French Pyrénées

By Karl North | March 7, 2024

A region of distinction in decline

French Catalonians commonly call their region Roussillon, but as one ascends from the coastal plain that stretches from the city of Narbonne to the Spanish border, first into the foothills, then into the narrow, steep-sided Tet river valley known as the Conflent, different landscapes take on different names. The last town with shops up the N116 national highway for 20 km. up a mountain gorge is Olette, population 600, where Larisa, my youngest child, received most of her elementary schooling. (Parenthetically, unhappy after her first exposure despite being ranked at the head of her class, Larisa quit school. After taking a year off playing in our mountain village with smaller kids, she reconsidered, and decided to return to her position as sole “étranger” in her class.)

A right turn off to the north from Olette takes one into the valley called Garrotxes, some of which borders on the township of Canaveilles, with its partly abandoned village perched at 3000’ along a ridge overlooking the Tet valley, where our family lived for most of the 1970s. Most of the rugged mountain terrain of the region had been under a variety of more or less intensive management until the end of subsistence farming communities circa 1960. But a decade later after the younger generation had left the mountains seeking an easier life, most of it had rewilded, and the locals called any wild place the garrotxes, which means “ the sticks” in Catalan.

Besides a school and a gendarmerie, Olette sports a restaurant, a café, a tabac, a pharmacy specializing in herbal cures and significantly, two dueling butcher shops. The family budget rarely allowed us to patronize either, even for “boudin”, or blood sausage, the cheapest next to tripe. However, the school sent its pupils to the restaurant, whose menu, created for the summer tourist trade, boasted local stream-grown trout and lamb chops, so my children ate meat daily.

Olette’s other distinctive landmark is its church, really a small cathedral, presumably because it was built to serve a wide region of mountain communities. Like most churches in a long-secularized France, it stood practically empty most days. Its young priest, Joseph, one of the three sons of the Flemish family Reymaakers (sp) who had relocated to the valley of the Garrotxes a generation before, was known locally as the hippy priest, for various reasons. One was his attractive assistant catechism teacher, who was rumored to be his girlfriend. Also, as young urban refugees began to filter in during France’s belated version of US sixties counterculture, Joseph, reduced mostly to circuit riding through the mountains, made several attempts, mostly rebuffed, to help the marginals, as they called themselves, settle in to mountain living. This put the priest in the unenviable position of mediator between the locals and the newcomers, who the remaining locals viewed as urban lightweights who would never last in a terrain so challenging that it had driven out most of their children.

Midnight mass on Christmas eve was one of the few times in a year when the Olette cathedral was packed to the gills, despite competition from the café, which held a rousing, inebriated bingo fest for the anti-clericals, a large population in southern France. Apparently, Joseph had learned that I had been studying classical guitar for several years, and decided to recruit me for a solo performance during the midnight mass. My little Bach prelude was reasonably successful, more because it was such a novelty at the annual midnight mass than for the quality of my playing.

Actually, my meager musical talents leaned toward choral singing and directing, so I offered to create a quartet to enhance midnight mass the next year with four-part harmony. In addition to my wife and myself, I recruited Helleke, a musician from Antwerp who lived in Llar, a hamlet in our township, in a house restored by one of Joseph’s brothers, whom she had married. I found a soprano to complete the quartet at the weekly farmers’ market in Prades, a meeting place of young newcomers to the region.

Looking to beef up the midnight mass that year, the priest was building what he hoped was an authentic Nativity Scene in the nave of the cathedral. I offered to lend my donkey, who was so old that some good hay next to the manger of the Christ Child would be enough to keep her stationary during the mass. The idea excited the priest at first, but then he backed away from the idea, fearing unexpected consequences.

Our quartet sang from the church gallery, hoping to sound like angels from the sky. The Reymaakers patriarch, a devout Christian who had built his own chapel on their farm, a promontory over looking the valley of the Garrotxes, voiced his approval of our choral performance as we exited the church after the mass. Hopefully this mitigated his unhappiness at the hippy priest reputation his son had gained, partly from fraternizing with us marginals.

A backstory

In the attempt to flee responsibilities of citizenship in a country that had used weapons of mass destruction to commit genocide and horrific environmental damage in poor, Third World countries of Southeast Asia, in 1973 I left an academic career path and moved with my wife and school-age children to begin an agrarian life in the small village of Canaveilles in the mountains of French Catalonia. The houses of the region, with their thick stone and clay walls and heavy slate roofs, are a testament to a bygone age of heroic struggle and tenacity in an intensely sunlit but difficult terrain, using primarily the simple materials that the mountain offered in abundance. Nearly abandoned after centuries of peasant subsistence farming, the village of Canaveilles, located at an altitude of 3500 ft, offered one of these houses and a barn, all attached to other houses in the clustered style of villages of old Europe. We bought the house and barn next door and began to rebuild it as we learned to farm the narrow terraces of the steep Mediterranean mountainside.

The irony of such a change of vocation was that my choice of social terrain, like the other dying peasant societies of the world, had become the intellectual focus of the anthropological discipline that four years of graduate school had trained me to study. However, having just escaped from an anthropological career, I was in no mood to consider the research possibilities of the remnants of Catalonian peasant life in my midst. Still, I suspect that the vignettes in this account cannot help but suffer from a residue of my previous intellectual life. Be advised, readers!

Canaveilles house and barn with solarized third floor and balcony

A first solar design experience

The house offered some ideal requisites of passive solar design. The front wall had full southern exposure to the intense sun of the region, but being two feet thick, kept out the both summer heat and the freezing temperatures of winter nights. The earth sheltered house has long been a favorite of energy efficient house designers. This house, in fact the whole street, was as if built to order. The north wall, chipped into the mountainside, provided the insulation equivalent of an endless earth berm. The side walls, shared with the neighbors, also supplied the high insulation values that are necessary to passive solar design. The mountainside behind the village sheltered it from the prevailing winds, including the Tramontane, a cousin to the dreaded Mistral, a three-day gale that often sweeps down the Rhone valley.

All these elements in combination with the forgiving Mediterranean climate – shirtsleeve temperatures on cloudless winter days – reduced the heat requirement and made our first solar design project easier. Compared to recommendations for thermal mass in the passive solar literature, the centuries-old, massive stone walls of this dwelling were overkill. And our rule of thumb learned in practice has been to cover as much of the south side of a house with glass as we could afford, then build in enough heat storage to handle the excess solar capture capacity of the south glass area.

Building on these advantages, we decided to raise the low garret third floor to become the main living space and glass in the front. Constructing the new living space was an exercise in the use of free and salvage materials, for our finances were no better than those of the remaining villagers. The river bank in the gorge below the village supplied free sand for the mortar to raise the walls. Wall stone came from ruins in the village. Rights as property owners gave us access to timber for beams and rafters in the village communal forest. Work parties of volunteers from around the region helped place the big beams, and helped with the heavy labor of removal of the old slate roof in exchange for room and board. In an abandoned commercial building in the region, we found windows at salvage prices, but large enough to be used as French doors, and installed them as the south wall of the living space. I include these details because they illustrate a low-cost approach to building (and to life) that will become increasingly necessary in the post-petroleum era.

The resulting passive solar renovation reduced firewood needs to less than a cord, which we could easily skid down behind a donkey from the forests above. We burned it in a small cookstove augmented by a fireplace I constructed in the local tradition, using a chestnut beam salvaged from the expansion of one of the Olette butcher shops. The chestnut was so old and dense that it struck sparks from the chainsaw.

Having been brought up in wooden houses, we found the experience of living within the permanence, security, and quiet of massive masonry walls unforgettable. Similarly, the feeling of being almost outdoors that the wall of French doors conveyed, in combination with the balcony just outside affording a spectacular panorama of a gorge rising to often snow-capped peaks, made living in the renovated house in Canaveilles a special experience. The 10000’ peak in the picture, eastern anchor of the Pyrénées range is visible from much of Roussillon. Called the Canigou, it still retains some of its sacred quality in the region. Houses and even whole villages orient themselves toward the it if they can, and when villages celebrate the summer solstice with bonfires throughout the region, volunteers climb the Canigou with firewood to celebrate the solstice there.

Donkey farming

To survive on the south face of a mountain in a Mediterranean climate, human communities had to initiate seemingly superhuman changes in the terrain: stone-walled terraces on which to build a village and grow food, and an irrigation canal cut into the mountainside for ten kilometers back along the ridge to meet the Tet river at 5000’ altitude at the city of Montlouis.

Flatlanders hoping to last long in this environment face a steep learning curve of physical conditioning, where almost every activity includes a stairway up or down. My survival plan started with growing gardens and animals for food, skills in which I had some elementary experience. After surviving the vicissitudes of cooperative projects with unreliable partners, we had learned enough to be mostly self-sufficient on our own. But growing anything required running up and down the mountain to direct irrigation water to fields and gardens, and to graze the dozen ewes and their annual lamb crop in pastures at different altitudes depending on the season. I needed to manure upper terraces, skid firewood and hay down to the village, and climb to the summer pastures.

I decided we needed a donkey. We also needed to acquire farmland to gain residential rights and benefits, both in the village and in France. As it happened, my friend the horse butcher, who held the second largest property in the township (after the mayor), managed to provide both. For $10 he offered me the aged donkey he had planned to slaughter, and for $75, annual rental of all his land, which gave me full irrigation rights.

The horse butcher delivered the rescued donkey, a coal-black animal, to me in the village at midnight, presumably after one of his regular drinking bouts, so I called her Mitjanit, ‘midnight’ in Catalan. I adapted some pieces of abandoned harness to allow Mitjanit to carry me, pull a travois (later fitted with wheels) and skid firewood tree trunks. At this point I thought we were equipped to begin to grow most of our food on the terraced mountainside, except for water.

Watering the Garotxe

Societies that depend on irrigation systems are so distinctive that some anthropologists have called them hydraulic civilizations. I discovered that this was true even at the small scale represented in the township of Canaveilles. Common to all such societies is a need for a water administration that maintains a complex man-made irrigation system and polices the sharing of water among the users. In our village it consisted of a committee elected by the land owners who had irrigation rights and a person hired each year to manage the canal and distribution of its water. The committee collects a tax from the users to pay for the annual cleaning and repairs, and to pay the canal manager. The cleaning crew often consists of users whose pay defrays the tax. Cleaning occurs in the early spring, after which the system is open for the growing season.

Like our village in the Pyrénées, small communities in the US south west created similar systems centuries ago. My wife and I once spent a month working on a farmstead on the side of the Sierra Nevada, a mountain range in Andalucia in southern Spain, watered from an irrigation system that dated back to Roman times, which the later Islamic civilization greatly refined.

Also characteristic of irrigation civilizations is the social bond the need for water creates, along with endless feuds over its management. This bond can be stronger than anything else that binds the community, including politics or religion. In Bali, religious control of water dropping through a series of rice paddy terraces has created a system that has lasted a thousand years, administered by priests in water temples erected at different levels of the irrigation system.

When our family settled in the village in 1973, the irrigation system suffered from lack of help. The year-round residents consisted of Parisian couple exiled to south of France as penance for having collaborated with the Nazis, a couple from the coastal plain who had fled a grocery scandal, and the only remaining local, an old woman who kept to herself. Both families included a married child and small goat herds. Until we arrived, only the Parisian actually needed the canal water for his gardens from the seasonal canal. Two spring developments with their troughs at each end of the village originally provided water for the residents. Now a cistern above town caught spring water and piped it to the houses. But without infiltrated water from the irrigation system all these springs dried up in summer. So everyone, including the summer people who still had ancestral abandoned irrigation land and paid the water tax, needed the canal to run.

The village water supply had not always depended so heavily on the canal. According to the Parisian, he was now the acting mayor because the elected mayor had sold the water rights to a hydroelectric company in return for a cottage and lifetime employment in the company down in Olette. The company had dug tunnels under the mountainside that drained the water, permanently lowering the water table. Another simmering scandal.

My first spring in the village found me learning to clean the canal with an unsatisfactorily small crew, most of whom were experienced locals who looked with disdain on the foreigner and chatted mostly in Catalan. The cleaning started at the head of the canal, which at 5000’ was still in wintry weather. As we worked for a week along it toward the end at 4500’ over the village we thus experienced an enjoyable rapid change of season. Half way along a shelter had been built shaped like an igloo of rocks gradually closing in at the top. Built on a promontory jutting out from the ridge, it offered a beautiful view of the Tet valley in both directions. The day the work party neared the shelter, I decided to bring bedding to camp out. The locals tried to scare me, saying the rock cabin was infested with vipers. I said I would take my chances, since unlike the rest I would not have to hike in and out for the next two day’s work.

Water wars

After its long, perilous itinerary cut into the side of a steep ridge, the canal proper ends far above the village in the summer pastures. Then a branching system of “rigoles” descends to eventually serve every property holding irrigation rights. A main split occurs where a large piece of shale with two equal holes set vertically across the rigole sends water into separate watersheds. Stories abound of blood shed at this location when angry irrigants hiked up, only to find one hole unlawfully blocked. Indeed, early in my adventure in learning irrigated agriculture I encountered a blocked hole at the fateful site. When I confronted the Parisian, who was the only other irrigant in the village at the time, he blithely suggested that debris floating down from the canal must have blocked the hole. Later, a water feud erupted between Canaveilles and Llar, its sister hamlet upstream, when the gardeners at Llar diverted the whole canal into their fields for a week. This provoked heated phone talks from the Parisian, who was the canal manager that year, to culprits at Llar.

Water supply was only one of the challenges encountered in the attempt to feed our family from our crops. A large planting of potatoes destined to feed ourselves and a couple of pigs as well suffered a heavy infestation of potato beetles despite good irrigation that year. The problem was that the soil was too depleted to grow a crop that could protect itself from the predators. I was to encounter the same worn-out soil later while reclaiming abandoned fields in upstate New York, and again when I restored a small farm to retire on in the state of Maine. (Eventually I developed a soil regeneration complex that integrated management-intensive grazing to maximize grass productivity and soil organic matter, and careful manure management with a bedding pack and composting to retain nutrients. The system I evolved is described in Illustrations and Challenges of Progress Toward Sustainability in the Northland Sheep Dairy Experience).

A number of other growing experiments failed or suffered from an unreliable water supply or predators ranging from insects to wild boars. My most successful food source became the gardens in the terrace just below our house and adjoined sheep barn. They benefitted from a compost pile from manure dug out of the barn and thrown over the wall, and from water I diverted from a rigole just above the village, using a garden hose and a filtered funnel. One of the gardens, located in a barnyard manured for centuries, well-watered in the hot Mediterranean sun, grew the largest yield of potatoes that I have ever produced. Crops in upper fields occasionally did well, but required the donkey Mitjanit to climb up through the terraced fields transporting compost, a job she knew well but did not relish at her advanced age.

Marginals and their Discontents

Like most of their counterparts in the US, European back-to-the-landers that I encountered arriving in numbers in the South of France in the 1970s were ill-equipped for life on the lam from urban civilization. Attracted to the sunny Mediterranean and its abandoned villages, a few with manual skills set to work restoring crumbling houses and barns. Even fewer had any notion of how to grow their own food. Others just sat in the sun until their cash ran out.

Two enterprising marginals I befriended succeeded for a while. One couple, after bouncing around living in caves and borrowed municipal buildings, purchased a property high above Canaveilles that provided a year-round spring and easy access to the road from the village up to the summer pastures. They built a little cabin and created a small grass-fed rabbit project selling dressed rabbit to the butchers at Olette. We shared machines – they borrowed the tiller the horse butcher had loaned me and I used their chainsaw. As we both were on a steep learning curve in machine maintenance, the implements suffered considerable damage at first. Then, wanting to enjoy aged pork, a delicacy of the Mediterranean that I had discovered on a student year in France, but little known to most Americans, Bernard, the husband, and I began a cooperative pig project. When we drove down to the seacoast to buy two sows, sensing something amiss, I asked Bernard if he had brought cash for his half of the deal. No, he confessed he expected me to pay for both, then agreed reluctantly to reimburse me. After a few days he abandoned the project altogether, leaving me with two big sows to feed. The pitfalls and joys of my pig project warrants its own story that I will tackle later in this tale.

The other couple, well capitalized Parisians, built a goat dairy lower in the Tet valley on relatively flat terrain, acquired hay lands and machinery, and made excellent cheese, all of which sold well at the weekly farmers market in Prades. They were gregarious, getting to know many people in the region, and hiring other marginals to help with haying and other chores, They introduced me to people at the local monastery, which was hosting several artist refugees from fascist Spain. One, a muralist, gave me my first sheep dog, a half-breed that we named Milou. The daughter of another refugee became my student when I had started giving introductory lessons in classical guitar. Eventually we began trading whole wheat bread my wife baked for gallons of milk from the goat dairy, thus adding a relatively cheap source of dairy to our diet. Their goat dairy, while successful for a while, languished when the husband got bored, retreated into his cannabis oil heaven and left all the work to his wife.

Cattle Wars

French fascination with the life and legends of the American far west – its cowboys and Indians, its cattle rustling gangs and the posses formed to fight them – has outlasted anything surviving in the US itself. An investor group in the north of France saw the chance for a low-cost cattle ranching scheme. Calling itself La Compagnie de la Californie, it made a deal with the mayors of our village and a neighboring township to put hundreds of cattle on our mountains under the management of a single, low-paid herdsman. Since the cattle were pastured on private property as well as municipal commons, the company sent letters with paltry rental payments to the land owners. The barely managed herd ranged far and wide, breaking down centuries-old terrace walls, rampaging through our crops and village streets, and many dying from brucellosis, which was still endemic in the region. The scam was justified as forest fire management, a legitimate concern in the no longer grazed grasslands and forest of the mostly abandoned townships.

As it happened, recent fire had occurred in our township. Presumably from the cigarette of a passing motorist, the fire raced up the steep forested mountain, burning mostly understory brushwood. The Parisian and I were able to stop it where the forest joined the summer pasture, and little was left to do but stamp out small fires in patches of thicker underbrush. The local fire brigade arrived in their elegant uniforms just in time see the last of our fire fight in the now smoking hillside.

Meanwhile, along with arrival of the cattle herd, our village and the whole region had seen an influx of marginals, including several households just in our village, who had begun to use the land for their crops and livestock. I was growing crops and pasturing sheep on property I rented from the horse butcher, second only to the mayor in the size of his holdings. The local gendarmes, regarding the marginals as rootless riffraff prone to cause trouble, were slow to respond to our repeated complaints of cattle damage. The mayors, fearing the loss of their cut of the cattle profits, fought back.

The chosen setting was the secluded little hot spring at the edge of the Tet, a quiet stream at that location. Offering both hot and cold bathing, it saw frequent visits by marginals, whose restored peasant dwellings had never included bathrooms. One day when a large group of us from the village hiked down to the hot spring, someone alerted the police, who appeared suddenly on the other side of the river to announce that our group, which included mothers and babies undressed for the bath, were under arrest for “atteinte à la pudeur publique”, or assault on the public’s chastity, a difficult crime to pull off in an isolated location never visited by any but a rare passing trout fisherman. The immediate outcome of this comic caper was a day the group had to spend at the Gendarmerie d’Olette, while embarrassed police watched mothers nursing and changing diapers on office desks. Finally, they dismissed us to await trial at the regional capital, Perpignan near the seacoast.

Convoked to stand trial many months later, the group discovered that the father of one of the young mothers, a successful apple orchardist in our vicinity, had engaged a lawyer. In our defense he exposed the hypocrisy of a justice system that prosecutes bathers in a secluded gorge while allowing Scandinavian vacationers to cavort naked on the beaches of Roussillon, presumably because they benefit the local tourist economy. The judge ruled us guilty with suspended punishment.

The cattle war accelerated, gaining the attention of local leftists who, to my surprise, often dominated politics in rural towns in the south of France. In our support they organized an attack on the government agency that had sold land to the cattle cartel, thus giving the cartel a foothold in our township. Government hearings revealed gross mismanagement, which weakened the Compagnie de la Californie and forced some reforms. Twenty years later when we returned to Canaveilles for a visit, the cattle cartel had disappeared.

Adventures in Jambon Land

Any farmer who manages to produce more than his family’s bare subsistence knows the value of a pig. Beyond its value as food and cooking fat, this omnivore exists to conserve in its body anything the farm produces that cannot be immediately consumed or sold. The same way livestock of all kinds have functioned for pastoralists for thousands of years, a pig serves as a living piggy bank, a savings account to draw on in times of need. And like the interest rate in a bank account, a sow can make piglets.

Even more important, almost all parts of the pig can be preserved without refrigeration, by salt curing and ageing for as much as a year or two, and whose flavor in my view is superior to cooked pork. Because the process cures the meat of trichinosis, the parasite that has caused Islam and Judaism to prohibit pork, aged ham has long been the cornerstone of good eating in the Christianized areas of the Mediterranean.

Having experienced the fine flavor of aged, uncooked ham during previous trips to the region, I decided to learn how to process a pig. Francis and Francoise, a younger couple who we helped construct makeshift living quarters next to our donkey shed, eagerly agreed to split the cost of a pig, as Francis’ family had relocated to France from Spain, reputed to produce the highest quality cured ham.

An expedition up the valley to La Cerdagne, a hanging valley at 5000’ whose large farms could afford to grow extra pork, netted us a 250 lb. animal. As luck would have it, the Figuères, an elderly couple who spent their weekends and summers down the street in their ancestral home, agreed to teach us the processing skills. Monsieur Figuère’s trade as a driver often included pig slaughter as a side enterprise. On the appointed day we gathered the specialized tools, all of which had come with the purchase of our property – a wooden trough in which to scald the pig and loosen the bristles, a cast iron cauldron to boil the water for scalding and later to cook the blood and white sausages, scrapers made from pieces of a broken scythe blade. We had been instructed to get up early to build a fire under the cauldron.

Monsieur Figuère brought a crucial implement – a wood handled steel rod with an arrow shaped end bent around into a hook. Inserted under the jaw, the pig was under complete control, and was quickly placed on the upturned trough for bleeding. My wife then received instruction in the wife’s traditional duty, which was to catch the blood in a bowl and stir it to prevent coagulation. The bled pig was placed in the trough with boiling water, scraped clean of bristles and dehooved with the hook. Then it was hung, gutted and split along the backbone. While the carcass was cooling for butchering, Mme Figuère fed everyone a lunch of the organ meats and aioli, the local garlic mayonnaise.

We spent the afternoon cutting and preparing fatback, hams and sides of bacon for salting, cutting the rest for grinding into sausage, and cleaning and soaking the intestines in the upper spring (la Fontaine) for stuffing. The next day the horse butcher ground the sausage and lent us his stuffer, and we spent the rest of the day salting and stuffing. After curing time, which varied from two weeks to a month, we enjoyed months of home processed animal protein.

Now we knew how to make ‘jambon de montagne’, the next project was to grow our own pork. Left with two large, hungry sows from the fiasco of the pig cooperative, the extra potatoes, mangles and wheat that I had grown began to disappear quickly as we boiled it into pig feed in the cauldron, a traditional way of making pig feed in the region. I tried to add garbage from the tourist restaurant and spa down next to the main highway, but separating the edible from other trash was soon too much work.

The butcher I knew as a customer for my lambs was slaughtering over a dozen lambs twice a week at the municipal slaughterhouse in Prades and throwing away most of the guts, so he let me spend the morning cleaning them in the stream running through the building and take a trash can of tripe home to add to the pig cauldron. A delicious aroma from the resultant stew permeated our end of the village. We even fished out some of the tripe to try ourselves. The carnivorous diet made the sows begin to eye us as food, and we were reduced to quickly throwing their feed into the trough and making an escape.

Our next project was to make piglets. I loaded Virginia Slim, the more friendly sow into our truck and drove her down the valley for a couple of weeks of mating with a boar. The eventual result was an oversize litter of 11 piglets, from which we were able to save only enough for the sow’s 9 spigots. The sale of weaned pigs at a livestock market day in Olette was a net loss except for the two the goat dairy bought, deciding us to end the pig project and convert the sows to jambon de montagne.

Liberated Ecclesiastics

In a Europe where a secular age had emptied the churches, ecclesiastics at loose ends cast about for new flocks with which to ply their trade. The challenge of the unemployed ecclesiastics expressed itself in our locale in two ways. Joseph, ‘the hippy priest of Olette’ who I introduced earlier in this account, tried convoking local marginals to a dinner get-together where he hoped to give some direction to their sudden appearance in his Parrish. The marginals rebuffed his efforts with reactions that ranged from amusement to anticlerical disdain. Joseph also rounded up budding juvenile delinquents and other street kids from the coastal towns for a day trip in the mountains to assist our spring canal cleaning. The locals on the cleaning crew, even more anticlerical than the marginals, were openly sarcastic all day. As one remarked in an aside, priests are the people who wear skirts (at least still when saying mass) and don’t work for a living.

The other manifestation of clerical liberation struck closer to home. On settling our family in Canaveilles we discovered that the meager village population included a resident nun. Frustrated with quiet convent life, Sister Marie-Christella had ventured out into the fast-changing world. She had adopted our village as her terrain of battle and launched a project to bring it back to life. As one of her first ventures, she obtained our use of an empty house and barn as temporary living quarters and midwifed negotiations with the distant owner for its eventual purchase.

As the village marginal population swelled, she focused on its children, first bringing them clothing from church charity donations. Then, to celebrate the village’s annual saint’s day, she trained them along with others from Olette for a grand performance in the village plaza of dances from different French folk traditions, replete with traditional costumes. She even dragooned me into organizing the kids to perform Catalan folk tunes.

Living her role to the hilt, Marie-Christella inhabited a tiny hermitage apart from the village, acquired a donkey to haul water to it, and wore sandals on bare feet year-round, presumably to symbolize her ascetic lifestyle. The Parisian complained that she was usurping his role as acting mayor, and accused her of being independently wealthy.

Staked alone in her pasture for any length of time, my donkey was pining away. Silent for days, she eventually let loose with a long and loud complaint of heehaws that reverberated through the mountains. I offered to stake the nun’s donkey with my Mitjanit, so that she would have company. In exchange, I had the use of her younger animal for fast trips up the mountain when I started milking ewes stationed to graze the summer pastures.

Afterword

Our séjour in the Eastern Pyrénées lasted nearly seven years and included many adventures that I have not recounted here. Our children continued reading and writing in two languages and performed song and dance in several French folk traditions. René learned to bake cakes and become a soccer star. Larisa learned to tolerate school as a foreigner at the top of her class.We learned a set of low-tech subsistence farming and homesteading skills whose integration into a low input farm design enabled us eventually to make a living at small scale farming later in the US. The memories of living in stone houses with long mountain vistas marked our attempts to build a farmstead on a hilltop in the rolling hills of upstate New York.

Watering the Garrotxes: donkey farming in the French Pyrénées

Karl North February 6, 2024

A region of distinction in decline

French Catalonians commonly call their region Roussillon, but as one ascends from the coastal plain that stretches from the city of Narbonne to the Spanish border, first into the foothills, then into the narrow, steep-sided Tet river valley known as the Conflent, different landscapes take on different names. The last town with shops up the N116 national highway for 20 km. up a mountain gorge is Olette, population 600, where Larisa, my youngest child, received most of her elementary schooling. (Parenthetically, unhappy after her first exposure despite being ranked at the head of her class, Larisa quit school. After taking a year off playing in our mountain village with smaller kids, she reconsidered, and decided to return to her position as sole “étranger” in her class.)

A right turn off to the north from Olette takes one into the valley called Garrotxes, some of which borders on the township of Canaveilles, with its partly abandoned village perched at 3000’ along a ridge overlooking the Tet valley, where our family lived for most of the 1970s. Most of the rugged mountain terrain of the region had been under a variety of more or less intensive management until the end of subsistence farming communities circa 1960. But a decade later after the younger generation had left the mountains seeking an easier life, most of it had rewilded, and the locals called any wild place the garrotxes, which means “ the sticks” in Catalan.

Besides a school and a gendarmerie, Olette sports a restaurant, a café, a tabac, a pharmacy specializing in herbal cures and significantly, two dueling butcher shops. The family budget rarely allowed us to patronize either, even for “boudin”, or blood sausage, the cheapest next to tripe. However, the school sent its pupils to the restaurant, whose menu, created for the summer tourist trade, boasted local stream-grown trout and lamb chops, so my children ate meat daily.

Olette’s other distinctive landmark is its church, really a small cathedral, presumably because it was built to serve a wide region of mountain communities. Like most churches in a long-secularized France, it stood practically empty most days. Its young priest, Joseph, one of the three sons of the Flemish family Reymaakers (sp) who had relocated to the valley of the Garrotxes a generation before, was known locally as the hippy priest, for various reasons. One was his attractive assistant catechism teacher, who was rumored to be his girlfriend. Also, as young urban refugees began to filter in during France’s belated version of US sixties counterculture, Joseph, reduced mostly to circuit riding through the mountains, made several attempts, mostly rebuffed, to help the marginals, as they called themselves, settle in to mountain living. This put the priest in the unenviable position of mediator between the locals and the newcomers, who the remaining locals viewed as urban lightweights who would never last in a terrain so challenging that it had driven out most of their children.

Midnight mass on Christmas eve was one of the few times in a year when the Olette cathedral was packed to the gills, despite competition from the café, which held a rousing, inebriated bingo fest for the anti-clericals, a large population in southern France. Apparently, Joseph had learned that I had been studying classical guitar for several years, and decided to recruit me for a solo performance during the midnight mass. My little Bach prelude was reasonably successful, more because it was such a novelty at the annual midnight mass than for the quality of my playing.

Actually, my meager musical talents leaned toward choral singing and directing, so I offered to create a quartet to enhance midnight mass the next year with four-part harmony. In addition to my wife and myself, I recruited Helleke, a musician who lived in Llar, a hamlet in our township, in a house restored by one of Joseph’s brothers. Who she had married. I found a soprano to complete the quartet at the weekly farmers’ market in Prades, a meeting place of young newcomers to the region.

Looking to beef up the midnight mass that year, the priest was building what he hoped was an authentic Nativity Scene in the nave of the cathedral. I offered to lend my donkey, who was so old that some good hay next to the manger of the Christ Child would be enough to keep her stationary during the mass. The idea excited the priest at first, but then he backed away from the idea, fearing unexpected consequences.

Our quartet sang from the church gallery, hoping to sound like angels from the sky. The Reymaakers patriarch, a devout Christian who had built his own chapel on their farm, a promontory over looking the valley of the Garrotxe, voiced his approval of our choral performance as we exited the church after the mass. Hopefully this mitigated his unhappiness at the hippy priest reputation his son had gained, partly from fraternizing with us marginals.

A backstory

In the attempt to flee responsibilities of citizenship in a country that had used weapons of mass destruction to commit genocide and horrific environmental damage in poor, Third World countries of Southeast Asia, in 1973 I left an academic career path and moved with my wife and school-age children to begin an agrarian life in the small village of Canaveilles in the mountains of French Catalonia. The houses of the region, with their thick stone and clay walls and heavy slate roofs, are a testament to a bygone age of heroic struggle and tenacity in an intensely sunlit but difficult terrain, using primarily the simple materials that the mountain offered in abundance. Nearly abandoned after centuries of peasant subsistence farming, the village of Canaveilles, located at an altitude of 3500 ft, offered one of these houses and a barn, all attached to other houses in the clustered style of villages of old Europe. We bought the house and barn next door and began to rebuild it as we learned to farm the narrow terraces of the steep Mediterranean mountainside.

Canaveilles house and barn with solarized third floor and balcony

A first solar design experience

The house offered some ideal requisites of passive solar design. The front wall had full southern exposure to the intense sun of the region, but being two feet thick, kept out the both summer heat and the freezing temperatures of winter nights. The earth sheltered house has long been a favorite of energy efficient house designers. This house, in fact the whole street, was as if built to order. The north wall, chipped into the mountainside, provided the insulation equivalent of an endless earth berm. The side walls, shared with the neighbors, also supplied the high insulation values that are necessary to passive solar design. The mountainside behind the village sheltered it from the prevailing winds, including the Tramontane, a cousin to the dreaded Mistral, a three-day gale that often sweeps down the Rhone valley.

All these elements in combination with the forgiving Mediterranean climate – shirtsleeve temperatures on cloudless winter days – reduced the heat requirement and made our first solar design project easier. Compared to recommendations for thermal mass in the passive solar literature, the centuries-old, massive stone walls of this dwelling were overkill. And our rule of thumb learned in practice has been to cover as much of the south side of a house with glass as we could afford, then build in enough heat storage to handle the excess solar capture capacity of the south glass area.

Building on these advantages, we decided to raise the low garret third floor to become the main living space and glass in the front. Constructing the new living space was an exercise in the use of free and salvage materials, for our finances were no better than those of the remaining villagers. The river bank in the gorge below the village supplied free sand for the mortar to raise the walls. Wall stone came from ruins in the village. Rights as property owners gave us access to timber for beams and rafters in the village communal forest. Work parties of volunteers from around the region helped place the big beams, and helped with the heavy labor of removal of the old slate roof in exchange for room and board. In an abandoned commercial building in the region, we found windows at salvage prices, but large enough to be used as French doors, and installed them as the south wall of the living space. I include these details because they illustrate a low-cost approach to building (and to life) that will become increasingly necessary in the post-petroleum era.

|

The resulting passive solar renovation reduced firewood needs to less than a cord, which we could easily skid down behind a donkey from the forests above. We burned it in a small cookstove augmented by a fireplace I constructed in the local tradition, using a chestnut beam salvaged from the expansion of one of the Olette butcher shops. The chestnut was so old and dense that it struck sparks from the chainsaw.

Having been brought up in wooden houses, we found the experience of living within the permanence, security, and quiet of massive masonry walls unforgettable. Similarly, the feeling of being almost outdoors that the wall of French doors conveyed, in combination with the balcony just outside affording a spectacular panorama of a gorge rising to often snow-capped peaks, made living in the renovated house in Canaveilles a special experience. The 10000’ peak in the picture, eastern anchor of the Pyrenees range is visible from much of Roussillon. Called the Canigou, it still retains some of its sacred quality in the region. Villages and even house orient themselves toward the it if they can, and when villages celebrate the summer solstice with bonfires throughout the region, volunteers climb the Canigou with firewood to celebrate the solstice there.

Donkey farming

To survive on the south face of a mountain in a Mediterranean climate, human communities had to initiate seemingly superhuman changes in the terrain: stone-walled terraces on which to build a village and grow food, and an irrigation canal cut into the mountainside for ten kilometers back along the ridge to meet the Tet river at 5000’ altitude at the city of Montlouis.

Flatlanders hoping to last long in this environment face a steep learning curve of physical conditioning, where almost every activity includes a stairway up or down. My survival plan started with growing gardens and animals for food, skills in which I had some elementary experience. After surviving the vicissitudes of cooperative projects with unreliable partners, we had learned enough to be mostly self-sufficient on our own. But growing anything required running up and down the mountain to bring irrigation water to fields and gardens, and to graze the dozen ewes and their annual lamb crop in many different pastures depending on the season. I needed to manure upper terraces, skid firewood and hay down to the village, and climb to the summer pastures.

I decided we needed a donkey. We also needed to acquire farmland to gain residential rights and benefits, both in the village and in France. As it happened, my friend the horse butcher, who held the second largest property in the township (after the mayor), managed to provide both. For $10 he offered me the aged donkey he had planned to slaughter, and for $75, annual rental of all his land, which gave me full irrigation rights.

The horse butcher delivered the rescued donkey, a coal-black animal, to me in the village at midnight, presumably after one of his regular drinking bouts, so I called her Mitjanit, ‘midnight’ in Catalan. I adapted some pieces of abandoned harness to allow Mitjanit to carry me, pull a travois (later fitted with wheels) and skid firewood tree trunks. At this point I thought we were equipped to begin to grow most of our food on the terraced mountainside, except for water.

Watering the Garotxe

Societies that depend on irrigation systems are so distinctive that some anthropologists have called them hydraulic civilizations. I discovered that this was true even at the small scale represented in the township of Canaveilles. Common to all such societies is a need for a water administration that maintains a complex man-made irrigation system and polices the sharing of water among the users. In our village it consisted of a committee elected by the land owners who had irrigation rights and a person hired each year to manage the canal and distribution of its water. The committee collects a tax from the users to pay for the annual cleaning and repairs, and to pay the canal manager. The cleaning crew often consists of users whose pay defrays the tax. Cleaning occurs in the early spring, after which the system is open for the growing season.

Like our village in the Pryenees, small communities in the US south west created similar systems centuries ago. My wife and I once spent a month working on a farmstead on the side of the Sierra Nevada, a mountain range in Andalucia in southern Spain, watered from an irrigation system that dated back to Roman times, which the later Islamic civilization greatly refined.

Also characteristic of irrigation civilizations is the social bond the need for water creates, along with endless feuds over its management. This bond can be stronger than anything else that binds the community, including politics or religion. In Bali, religious control of water dropping through a series of rice paddy terraces has created a system that has lasted a thousand years, administered by priests in water temples erected at different levels of the irrigation system.

When our family settled in the village in 1973, the irrigation system suffered from lack of help. The year-round residents consisted of Parisian couple exiled to south of France as penance for having collaborated with the Nazis, a couple from the coastal plain who had fled a grocery scandal, and the only remaining local, an old woman who kept to herself. Both families included a married child and small goat herds. Until we arrived, only the Parisian actually needed the canal water for his gardens from the seasonal canal. Two spring developments with their troughs at each end of the village originally provided water for the residents. Now a cistern above town caught spring water and piped it to the houses. But without infiltrated water from the irrigation system all these springs dried up in summer. So everyone, including the summer people who still had ancestral abandoned irrigation land and paid the water tax, needed the canal to run.

The village water supply had not always depended so heavily on the canal. According to the Parisian, he was now the acting mayor because the elected mayor had sold the water rights to a hydroelectric company in return for a cottage and lifetime employment in the company down in Olette. The company had dug tunnels under the mountainside that drained the water, permanently lowering the water table. Another simmering scandal.

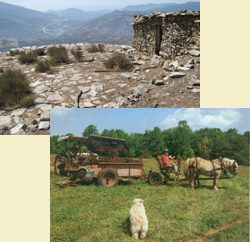

My first spring in the village found me learning to clean the canal with an unsatisfactorily small crew, most of whom were experienced locals who looked with disdain on the foreigner and chatted mostly in Catalan. The cleaning started at the head of the canal, which at 5000’ was still in wintry weather. As we worked for a week along it toward the end at 4500’ over the village we thus experienced an enjoyable rapid change of season. Half way along a shelter had been built shaped like an igloo of rocks gradually closing in at the top. Built on a promontory jutting out from the ridge, it offered a beautiful view of the Tet valley in both directions. The day the work party neared the shelter, I decided to bring bedding to camp out. The locals tried to scare me, saying the rock cabin was infested with vipers. I said I would take my chances, since unlike the rest I would not have to hike in and out for the next two day’s work.

View from the canal

Water wars

After its long fragile itinerary cut into the side of a steep ridge, the canal proper ends far above the village in the summer pastures. Then a branching system of “rigoles” descends to eventually serve every property holding irrigation rights. A main split occurs where a large piece of shale with two equal holes set vertically across the rigole sends water into separate watersheds. Stories abound of blood shed at this location when angry irrigants hiked up, only to find one hole unlawfully blocked. Indeed, early in my adventure in learning irrigated agriculture I encountered a blocked hole at the fateful site. When I confronted the Parisian, who was the only other irrigant in the village at the time, he blithely suggested that debris floating down from the canal must have blocked the hole. Later, a water feud erupted between Canaveilles and Llar, its sister hamlet upstream, when the gardeners at Llar diverted the whole canal into their fields for a week. This provoked heated phone talks from the Parisian, who was the canal manager that year, to culprits at Llar.

Water supply was only one of the challenges encountered in the attempt to feed our family from our crops. A large planting of potatoes destined to feed ourselves and a couple of pigs as well suffered a heavy infestation of potato beetles despite good irrigation that year. The problem was that the soil was too depleted to grow a crop that could protect itself from the predators. I was to encounter the same worn-out soil later while reclaiming abandoned fields in upstate New York, and again when I rebuilt a small farm to retire on in the state of Maine. (Eventually I developed a soil regeneration complex that integrated management-intensive grazing to maximize grass productivity and soil organic matter, and careful manure management with a bedding pack and composting to retain nutrients. The system I evolved is described in Illustrations and Challenges of Progress Toward Sustainability in the Northland Sheep Dairy Experience).

A number of other growing experiments failed or suffered from an unreliable water supply or predators ranging from insects to wild boars. My most successful food source became the gardens in the terrace just below our house and adjoined sheep barn. They benefitted from a compost pile from manure dug out of the barn and thrown over the wall, and from water I tapped from a rigole just above the village, using a garden hose and a filtered funnel. One of the gardens, located in a barnyard manured for centuries, well-watered in the hot Mediterranean sun, grew the largest yield of potatoes that I have ever produced. Crops in upper fields occasionally did well, but required the donkey Mitjanit to climb up through the terraced fields transporting compost, a job she knew well but did not relish at her advanced age.

Marginals and their Discontents

Like most of their counterparts in the US, European back-to-the-landers that I encountered arriving in numbers in the South of France in the 1970s were ill-equipped for life on the lam from urban civilization. Attracted to the sunny Mediterranean and its abandoned villages, a few with manual skills set to work restoring crumbling houses and barns. Even fewer had any notion of how to grow their own food. Others just sat in the sun until their cash ran out.

Two enterprising marginals I befriended succeeded for a while. One couple, after bouncing around living in caves and borrowed municipal buildings, purchased a property high above Canaveilles that provided a year-round spring and easy access to the road from the village up to the summer pastures. They built a little cabin and created a small grass-fed rabbit project selling dressed rabbit to the butchers at Olette. We shared machines – they borrowed the tiller the horse butcher had loaned me and I used their chainsaw. As we both were on a steep learning curve in machine maintenance, the implements suffered considerable damage at first. Then, wanting to enjoy aged pork, a delicacy of the Mediterranean that I had discovered on a student year in France, but little known to most Americans, Bernard, the husband, and I began a cooperative pig project. When we drove down to the seacoast to buy two sows, sensing something amiss, I asked Bernard if he had brought cash for his half of the deal. No, he confessed he expected me to pay for both, then agreed reluctantly to reimburse me. After a few days he abandoned the project altogether, leaving me with two big sows to feed. The pitfalls and joys of my pig project warrants its own story that I will tackle later in this tale.

The other couple, well capitalized Parisians, built a goat dairy lower in the Tet valley on relatively flat terrain, acquired hay lands and machinery, and made excellent cheese, all of which sold well at the weekly farmers market in Prades. They were gregarious, getting to know many people in the region, and hiring other marginals to help with haying and other chores, They introduced me to people at the local monastery, which was hosting several artist refugees from fascist Spain. One, a muralist, gave me my first sheep dog, a half-breed that we named Milou. The daughter of another refugee became my student when I had started giving introductory lessons in classical guitar. Eventually we began trading whole wheat bread my wife baked for gallons of milk from the goat dairy, thus adding a relatively cheap source of dairy to our diet. Their goat dairy, while successful for a while, languished when the husband got bored, retreated into his cannabis oil heaven and left all the work to his wife.

Cattle Wars

French fascination with the life and legends of the American far west – its cowboys and Indians, its cattle rustling gangs and the posses formed to fight them – has outlasted anything surviving in the US itself. An investor group in the north of France saw the chance for a low-cost cattle ranching scheme. Calling itself La Compagnie de la Californie, it made a deal with the mayors of our village and a neighboring township to put hundreds of cattle on our mountains under the management of a single, low-paid herdsman. Since the cattle were pastured on private property as well as municipal commons, the company sent letters with paltry payments to the land owners. The barely managed herd ranged far and wide, breaking down centuries-old terrace walls, rampaging through crops and village streets, and many dying from brucellosis, which was still endemic in the region. The scam was justified as forest fire management, a legitimate concern in the no longer grazed grasslands and forest of the mostly abandoned townships.

As it happened, recent fire had occurred in our township. Presumably from the cigarette of a passing motorist, the fire raced up the steep forested mountain, burning mostly understory brushwood. The Parisian and I were able to stop it where the forest joined the summer pasture, and little was left but small fires from patches of thicker underbrush. The local firemen arrived in their elegant uniforms just in time see the last of our fire fight in the now smoking hillside.

Meanwhile, along with arrival of the cattle herd, our village and the whole region had seen an influx of marginals, including several households just in our village, who had begun to use the land for their crops and livestock. I was growing crops and pasturing sheep on property I rented from the horse butcher, second only to the mayor in the size of his holdings. The local gendarmes, regarding the marginals as rootless riffraff prone to cause trouble, were slow to respond to our repeated complaints of cattle damage. The mayors, fearing the loss of their cut of the cattle profits, fought back.

The chosen setting was the secluded little hot spring at the edge of the Tet, a quiet stream at that location. Offering both hot and cold bathing, it saw frequent visits by marginals, whose restored peasant dwellings had never included bathrooms. One day when a large group of us from the village hiked down to the hot spring, someone alerted the police, who appeared suddenly on the other side of the river to announce that our group, which included mothers and babies undressed for the bath, were under arrest for “atteinte à la pudeur publique”, or assault on the public’s chastity, a difficult crime to pull off in an isolated location never visited by any but a rare passing trout fisherman. The immediate outcome of this comic caper was a day the group had to spend at the Gendarmerie d’Olette, while embarrassed police watched mothers nursing and changing diapers on office desks. Finally, they dismissed us to await trial at the regional capital, Perpignan near the seacoast.

Convoked to stand trial many months later, the group discovered that the father of one of the young mothers, a successful apple orchardist in our vicinity, had engaged a lawyer. In our defense he exposed the hypocrisy of a justice system that prosecutes bathers in a secluded gorge while allowing Scandinavian vacationers to cavort naked on the beaches of Roussillon, presumably because they benefit the local tourist economy. The judge ruled us guilty with suspended punishment.

The cattle war accelerated, gaining the attention of local leftists who, to my surprise, often dominated politics in rural towns in the south of France. In our support they organized an attack on the government agency that had sold land to the cattle cartel, thus giving the cartel a foothold in our township. Government hearings revealed gross mismanagement, which weakened the Companie de la Californie and forced some reforms. Twenty years later when we returned to Canaveilles for a visit, the cattle cartel had disappeared.

Adventures in Jambon Land

Liberated Ecclesiastics

In a Europe where a secular age had emptied the churches, ecclesiastics at loose ends cast about for new flocks with which to ply their trade. The challenge of the unemployed ecclesiastics expressed itself in our locale in two ways. Joseph, ‘the hippy priest of Olette’ who I introduced earlier in this account, tried convoking local marginals to a dinner get-together where he hoped to give some direction to their sudden appearance in his Parrish. The marginals rebuffed his efforts with reactions that ranged from amusement to anticlerical disdain. He also rounded up budding juvenile delinquents and other street kids from the coastal towns for a day trip in the mountains to assist our spring canal cleaning. The locals on the cleaning crew, even more anticlerical than the marginals, were openly sarcastic all day. As one remarked in an aside, priests are the people who wear skirts (at least still when saying mass) and don’t work for a living.

The other manifestation of clerical liberation struck closer to home. On settling our family in Canaveilles we discovered that the meager village population included a resident nun. Frustrated with quiet convent life, Sister Marie-Christella had ventured out into the fast-changing world. She had adopted our village as her terrain of battle and launched a project to bring it back to life. As one of her first ventures, she obtained our use of an empty house and barn as temporary living quarters and midwifed negotiations with the distant owner for its eventual purchase.

As the village marginal population swelled, she focused on its children, first bringing them clothing from church charity donations. Then, to celebrate the village’s annual saint’s day, she trained them along with others from Olette for a grand performance in the village plaza of dances from different French folk traditions, replete with traditional costumes. She even dragooned me into organizing the kids to perform Catalan folk tunes.

Living her role to the hilt, Marie-Christella inhabited a tiny hermitage apart from the village, acquired a donkey to haul water to it, and wore sandals on bare feet year-round, presumably to symbolize her ascetic lifestyle. The Parisian complained that she was usurping his role as acting mayor, and accused her of being independently wealthy.

Afterword

Our séjour in the Eastern Pyrénées lasted nearly seven years and including many adventures that I have not recounted here. We learned a set of low-tech subsistence farming and homesteading skills whose integration into a low input farm design enabled us eventually to make a living at small scale farming later in the US. The memories of living in stone houses with long mountain vistas marked our attempts to build a farmstead on a hilltop in the rolling hills of upstate New York.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Memoires, Uncategorized | No Comments »