The Orange Revolution Comes Home to Roost?

By Karl North | August 30, 2020

The orange revolution, sometimes labeled simply ‘color revolution’, is a project of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), an organization set up to facilitate the penetration of Western private capital in every part of the world.[1] As such, one of the tasks of the CIA is to destroy revolts against compliant governments, and to destabilize and eventually overthrow governments that resist Western imperial penetration in any way. The orange revolution is one of the CIA projects designed to achieve these goals. This essay explores the thesis that the current violence in the US against property and police, piggy-backed on the Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations, is an attempt at an orange revolution.

The orange revolution is rooted in attempts to block anti-capitalist movements in Western Europe spawned by the crisis of capitalist economies in the 1930s and just after WWII. The first attempt was called Operation Gladio, which carried out assassinations of conservative political leaders in Italy and blamed them on the leftist parties, successfully decimating the Italian left.[2] The success of Operation Gladio led the CIA to expand it into a diversity of subversive Cold War operations in Europe and other parts of the world.[3]

Attempts to overthrow governments in Eastern Europe after the fall of the USSR, in Afghanistan in the 1980s, and more recently in the Arab world became known as orange revolutions. One of their trademarks is to piggyback violent extremist groups on peaceful protest demonstrations, to destabilize and spearhead the overthrow of elected governments. If this goal is not achieved, the back-up plan is to split a nation into separate parts and thus facilitate eventual capitalist penetration. Examples to date are Yugoslavia, Georgia, Ukraine, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria. The risk of blowback in the use of extremists has led to loss of control in all these cases and others as well. As we will see, if there is an attempt to foment a US orange revolution against the current Trump administration, the same loss of control is occurring.

When the candidate of the ruling elites failed to capture the US presidency in 2016, they managed to harass the winner into continuing to follow their chosen foreign policies. The elite controlled mainstream media (MSM) , always a tool of mass deception, was ramped up to become the weapon of the opposing Democratic Party in a series of attempts to impeach the president, using false evidence. This succeeded in keeping the sitting administration off balance and more or less subservient to ruling class interests, but the president, emotionally unstable and incompetent to govern but expert at playing the MSM, remained a loose cannon. As the next election approached, the death of a black man at the hands of the police provided an opportunity to block the re-election of the Trump administration, or at least cause enough destruction of the social order to justify imposition of martial law.

Heavily funded by US corporations[4] and George Soros[5], the sponsor of orange revolution projects in Europe, the BLM umbrella organization fielded demonstrations around the nation against racist police violence. The MSM went into attack mode, encouraging the budding protest, and focusing on the peaceful demonstrations while minimizing reportage of the widespread violence to commercial and government property. The extremist fringe of white liberalism piggybacked on the demonstrations against racism, calling for revolution, trashing commercial property, pulling down statues of historical figures, and using the peaceful demonstrations as a cover for violent attacks on police stations, federal buildings and other symbols of law and order. Democratic politicians at city and state level supported the violence by allowing activists to declare “police-free zones”[6] and making vague calls for defunding the police. All this occurred against the backdrop of a collapsing economy and an out of control virus epidemic that is accelerating the collapse. Conditions are building that might support an insurrection.

What are the indications from these events that a budding orange revolution is taking place in the US? The CIA playbook of orange revolutions in other countries has sought regime change, or barring that, weakening states so that they partition into mini-fiefdoms that transnational capital can more easily manipulate. In the US, no highly organized movement with popular support exists on which to graft a violent, extremist spearhead such as occurred, for example, in Afghanistan, Syria, or the former Yugoslavia. US ruling elites have seized on BLM as pawns in an effort to discredit the Trump administration, using the MSM and the Democratic Party to magnify its effect, but much of the white working class and even parts of lower class minorities are either politically hostile to BLM, or are reacting negatively to the effects of the protest demonstrations across the country, as the following synopsis of investigative reporting will show.

Investigative reporter Michael Tracey crisscrossed the country talking to residents of neighborhoods trashed by extremist activists. His long interview and photo essay reveals interesting patterns that suggest a situation out of control from the perspective of orange revolution goals.[7] Tracey found that most of the destruction of commercial property occurred in low income neighborhoods, often to businesses owned by minorities residing in those neighborhoods. Local residents reported that the riot damage aggravated a local economic situation already in crisis. Tracey discovered a common pattern across the country where according to locals interviewed, mostly white activists from outside the neighborhoods carried out the initial destruction. Then, profiting from the weakened police protection, low income locals looted the trashed businesses. Interviews show that, far from supporting the demonstrations, local residents deplored the destruction and the lack of police protection. Many locally owned businesses had to put up “black owned” or “minority owned” signs to protect them from rioters:

Anecdotally, a retired academic friend in Minneapolis, one of the hardest hit cities, reports that due to the absence of police protection, burglars have initiated a crime wave in his upper middle class residential district. It shows how far the breakdown of law and order can spread.

If the immediate goal was to provoke a reaction from the Trump administration that could potentially be used against him in the electoral campaign, it succeeded. Federal agents were deployed, both overtly and covertly, to fight rioters in cities where local police had been enfeebled by BLM anti-police demonstrations backed by local authorities. But apart from an enraged outcry in the MSM, supported by liberals from neighborhoods not hurt by the violence, much of the lower income populace, including minorities, seems to support law and order more than they deplore police violence. This could work in favor of a Trump administration victory in November. To the extent that a BLM orchestrated uprising has gotten out of control and could backfire in the short run, it fits the pattern of blowback that has characterized orange revolutions elsewhere.

A long-term strategy of ruling elites has been divide-and-rule: in the case of the US to polarize the country racially or ethnically. The secondary goal is to divert attention from the deepening economic crisis caused by de-industrialization and by an underlying predicament: the depletion of the industrial resource base worldwide. If the immediate goal is to provoke enough disorder to justify a martial law or police state solution, that may succeed, but in ways that are impossible to predict, given the loss of control of the current unrest. One likely result, the US descending into a civil war, might backfire against a ruling class that needs a state sufficiently in control to continue funding the military industrial complex that defends financial class investments in the imperial periphery.

In conclusion, the success of ruling elites at polarizing the country and diverting attention from its deepening class warfare ironically make the success of a putative orange revolution hard to achieve in the short run. However, one characteristic of the CIA orange revolution playbook is a long gestation period of hybrid warfare leading up to a coup d’état intended to achieve its goals. The use of the BLM may be a trial balloon to develop strategy for the long haul.

[1] Prouty, L. Fletcher, The Secret Team: The CIA and its Allies in Control of the United States and the World. Prouty is a former CIA officer who held a key position in the organization.

[2] Williams, Paul L., Operation Gladio: The Unholy Alliance between the Vatican, the CIA, and the Mafia.

[3] Cottrell, Richard, Gladii, NATO’s Dagger at the Heart of Europe: The Pentagon-Nazi-Mafia Terror Axis.

[4] Corporate America Pledges $1.7 Billion to Black Lives Matter

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/13/us/politics/george-soros-racial-justice-organizations.html

http://www.informationliberation.com/?id=61533

[6] https://townhall.com/tipsheet/mattvespa/2020/07/31/insane-seattle-moves-to-abolish-police-force-n2573513

[7] https://medium.com/@mtracey/two-months-since-the-riots-and-still-no-national-conversation-12a7e3e4e006

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

The Making of a Radical Worldview

By Karl North | July 20, 2020

Recently I was contacted by someone who had been drawn into the life of the alternative high school, Rochester Educational Alternatives, an experiment I attempted during our time in Rochester. A conversation ensued in which he wondered what in my background was responsible for my decision to create a radical alternative to public schooling. This slice of autobiography was my answer.

At about age 16-18 I began to question what I call the official narrative about how our society works – a narrative that comes all our lives in an endless flood from US leaders, mainstream media and most school education right up through doctoral level degree programs, especially in sensitive fields like economics, political science and history. For me, first questions revealed myths, generated more questions and revealed more myths in a domino effect. Spurred by experiences that I will describe in this essay, my disillusionment with the official narrative suffered exponential growth. Not immediately clear was why this occurred in my case, and so rarely in others. My parents were scientists, apparently vaguely liberal, and rarely talked politics or social issues.

However, although I did not reflect on it until much later, my early childhood was unusual, partly due to deliberate parental choices. They were outdoors people in their free time, gardeners and tent campers, and unlike most of their professional class, elected to raise their children on a farm as the best chance of a healthy upbringing. In those war years they rented the ageing Victorian farmhouse on a working farm in New Jersey that produced a rotation of potatoes, wheat and alfalfa, managed and worked completely by a black farmer who was paid a pittance by the absent property owner and had to work with dilapidated machinery. South Jersey at that time was Dixieland. This black farm manager and his family lived in a shack with no plumbing or electricity behind the farm buildings. I followed him around everywhere as a 6-12-year-old, and he indulged my interest in all the exciting farm activities, letting me ride the machinery. He deliberately taught me things like how to cut seed potatoes properly, and a quick trick to tie off a sack of wheat or potatoes, and inadvertently taught me about living while black. As far as I know, I was the only white person to spend time with his family in their shack. He was my closest adult friend beyond my parents.

My parents were frugal New Englanders and did not go for the frills their income could have provided us, but we enjoyed some version of the upper middle-class standard of living. Hence the contrast between our farmhouse and the shack out back was stark, but I had no framework for understanding it for many years, not from my parents or school teachers or anyone else. The closest neighboring children my age were poor or working-class whites. The farm across the road produced that same crops with good machinery but were prosperous and wintered in Florida. I followed their teenager in his chores: milking the family cow, feeding their handful of pigs, collecting eggs for a side business for sale to us and the nearest general store. He and his older sister had riding horses. I think this unusual environment in early life began to color, much later, how I saw the world in later life.

My parents taught me how physical and biological things worked, and enough reading and numbers to feed my interest in building and growing things. As little of that hands-on activity was offered in school, I did well grade-wise and the school once considered having me skip a grade, but I quickly got bored. “Karl spends class time looking out the window” was the first-grade teacher’s explanation for flunking me in “citizenship” on my report card. I began to get a dim view of formal schooling. I was sustained in school luckily by excellent music teachers right up through high school.

Starting in my last year in high school, a series of experiences began to deepen my educational disillusionment and changed my perspective on US society. My father was given a sabbatical year off and decided to spend it interacting with colleagues in his field in Germany. The whole family went to Europe to take advantage of the experience. I spent the year as a boarding student at the Ecole Internationale de Genève. Joe Dassin, later to become a famous French pop singer, lived across the hall. The McCarthy witch hunts had destroyed his father Jules’ successful US career as a film maker, and the family moved to France where his films as a US expatriate made him famous again. In my ignorance of both US politics and European culture, I knew nothing of Joe’s family history until much later. We were both musically inclined, however, and created a quartet that performed black spirituals at a school event. An Ecolint tradition was to organize a mock UN session, for which the Geneva UN conference hall and its language translators were put at our disposal. Students each chose to represent a particular country. Joe captured the coveted role of Soviet representative, and played the role to the hilt.

Another innovative tradition at Ecolint was a kind of scavenger hunt competition. It sent teams of senior boys on their own with a small budget and a free rail pass all over Switzerland, solving problems set to us by the organizers at each stop to gain intelligence on where to go next. Joe, the cosmopolitan European, was disgusted to find himself teamed up with three naïve Americans including myself, but I learned a lot from him as we traveled together. The breadth of perspective and self-confidence achieved in those four days was dramatic, one that I have always tried to reproduce in designing learning projects as a teacher. That event is an example of the capacity for independent action and self-motivation expected of secondary and college age students in Europe, very different from the ‘in loco parentis’ approach common in the US.

Another example of the European approach that became a major learning event for me was the school’s decision on what to do with a few students like me left at school during spring vacation, when parents had signed up most students for expensive group tours. The school asked an Ecolint alumnus who was attending Geneva University to design a low-cost vacation for the remnant. His plan, which the school administration accepted without hesitation, was to lead the half dozen students, all from different national backgrounds and some barely acquainted with one another, on a walking tour around the coast of Corsica, camping out along the way on beaches or in barns in case of rain, and eating bread, cheese and other foods we might purchase in villages and from local peasant farmers. Like the scavenger hunt, this trip was a highly memorable experience. It put me in constant contact with another rural European landscape and people in a beautiful Mediterranean setting, and a wonderful daily group learning challenge in a deliberately unstructured way.

I came away from that year highly impressed with the much longer historical depth of European society and culture, evident in its landscapes and centuries-old architecture, and in its approach to education, compared to the US. I was intent on returning to Europe as soon as possible for more learning from living in foreign places.

My undergraduate years were marked by two interruptions that gradually made me a critic of what was called the ‘liberal arts education’. I came to view it as a smorgasbord taught by specialists who mostly had not the breadth of enough general education to help students connect the dots into the holistic approach that I was beginning to see was a necessary tool for learning about the world and navigating intelligently through life.

The first interruption came at the end of my freshman year when a combination of poor course counseling, a broken leg in a skiing accident and my own misjudgment of my intellecual talents led the school to require a leave of absence to gain a better grip on my educational goals. At that point all I wanted to do was return to Europe, but was not enterprising enough to find a way to support myself. Instead, because by leaving college I automatically became eligible for the draft, I was pressured into volunteering for two years in the army. This turned into a major educational event, for I was thrown in daily association with the very lower class with whom I had lived my early childhood, but had been separated from in college tracking in secondary school, and in the prestigious liberal arts college itself, full of students from affluent classes. Moreover, of the three radio operators in our unit beside myself, the black one was by far the best, reputed to be the fastest Morse code guy in the regiment. He was the first black person I had contact with since early childhood, and became friends despite the racial tensions kept barely under control by the army discipline and regimentation. One time he and I were asked to take a jeep to the regimental field camp deep into the state of Virginia, a hundred miles south of the main army base in Maryland. I was still so naïve that when we stopped at a restaurant for lunch he laughed when I asked why he refused to enter. We were traveling in Dixieland in 1959 – and in restaurants, no niggers allowed.

Because of my unusual childhood, I discovered that blacks sensed that I was approachable, at least enough to be engaged in conversation. The other black in our communications platoon, who inhabited a neighboring cubicle in the dormitory, liked to tell me about his career strategy for moving up in the service, and leaving ghetto life behind. He had invested in tailored versions of army fatigues or work clothes, starched laundering, and had become the spiffiest dresser in the platoon, with boots spit-shined like mirrors.

I was a good radio operator but a lackadaisical soldier, and the army was so relieved that the end of my service approached that they let me out a month early “to readapt to college life”. Actually, after two years of rubbing shoulders with a class of people for whom army life was an improvement, the general run of students back in my prestigious liberal arts college struck me as incredibly insensible to how most of the world lives.

I now had a better plan for weathering higher education, this time with an interruption of my own design. I had taken courses in French Literature and European history in the army, and was the only French major who spoke passable French, with which I persuaded the department and Wesleyan University to let me enter a Junior year in Paris program, for credit.

Meanwhile as a sophomore I had discovered Norman O. Brown, later to emerge for some as a sixties counter-culture hero, and perhaps the only transdisciplinary polymath on the faculty. He had sallied forth from his obscure position in the classics department to teach a course that delivered a resounding critique of Western Civilization, bringing to bear history, Marxian political economy, Freudian depth psychology, anthropology, and of course Greco-Roman classical literature and mythology, a course based on his most well-known book, Life Against Death. Loathed by all the faculty whose fields he had invaded, he eventually left for Berkeley, and thence to Rochester University, where I reconnected with him as an anthropology graduate student there, and sat in on his course (again).

The Paris of 1960 was perfect for the making of a US radical. The culture available ranged from Lolita and Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the bookstalls by the Seine to large academic bookstores devoted to leftist literature, to a broad spectrum of journalism unknown in the United States. One eye opener was that the European editions of even Time and Newsweek were markedly different from the US editions my parents subscribed to back home. The tone and substance in the latter generally conformed to the values and beliefs of the official narrative, a set of fairy tales that most Americans who lived in foreign countries for any length of time would no longer swallow.

I enrolled in a course on Marx at the Institute des Sciences Politiques. The French colonies were declaring independence, Algeria was winning its war of liberation, and that fall an alliance of students and labor unions organized a huge demonstration in Paris for Algerian independence. The demonstration was brutally crushed by the Paris police whose head had been a Nazi collaborator during the war. The De Gaulle government had declared in favor of Algerian independence, so the right-wing army officer faction leading the fight in Algeria to keep it French threatened to overthrow the French government. Every morning for a while I walked past machine gun emplacements at street corners, to protect the prime minister’s residence, whose back garden opened on the block where I lived.

I was fluent in French, but the Sorbonne was overrun with foreign students, so the French students mostly ignored us. Instead I found French acquaintances in low income retail workers who lunched by the Seine on nice days – midinettes they were called. One invited me to fancy Sunday dinner with her family. They got me drunk on many different wines and took me on a tour of the palace of Versailles. A gay French arts student once tried to pick me up, but eventually gave up and introduced me to a female friend of his, also a student at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. They got me accepted at the student restaurant at their school, a rollicking place with better food than the gloomy student restaurant I had been assigned to as a foreigner. In the Spring I met an unemployed film crew worker from Avignon. We hitched a produce truck heading back south at midnight from the main Paris Market, borrowed his brother’s Lambretta in Avignon, and rode on it through Spain for a month living on a shoestring, staying mostly in youth hostels or beaches. Hitch hiking back from Avignon after the trip, I traveled with a nun for the whole two-day ride to Paris. At night she dropped me off at the local youth hostel and picked me up in the morning.

By the time I returned to the US from France, I saw a senior year in college as a distinct anticlimax, an ordeal to be endured. My fiancé and I already had decided to seek a teaching job in Africa that avoided the Peace Corps. My regular college work suffered because my time was taken with studying African affairs at night with a visiting professor for no credit, because the college did not offer such courses. I almost flunked out (again) because I failed to finish an assigned paper for an independent study course, run by the only other Marxist on the faculty, an old guy hidden away in the French department. It was actually an interesting project, studying the Paris Commune of 1870 via one of its newspapers, but my focus of study had already become Africa. I had learned that the better one is prepared for living in a foreign society, the deeper the experience.

By the time we reached our jobs teaching secondary school English as a foreign language in the left-leaning Republique du Mali, I was conversant enough with French culture and with the political economy of the decolonization process in which we were immersed to make the two years in Africa a valuable learning process. Occasional close encounters with the US diplomatic community in Mali sharpened my critique of US foreign policy. The bloated staff running a small USAID program made the Malians suspicious that they were all CIA. So, the Malians banned all unchaperoned US diplomatic community travel beyond the capital city and closed down the USIA library. As employees of the Malian Ministry of Education, Jane and I were almost the only Americans who had the run of the country. On breaks from teaching we visited Malian teachers we had met in a summer intensive language program and the family homes of our students, who came from all over the country as far as Timbuktu. We explored other countries in West Africa. On close inspection I saw most formal political decolonization as a cover for continuation of the previous colonial economy and its pillage. Once a USAID guy I did not know learned of our travels, invited us to dinner and tried to interrogate us.

The culture shock of every return to the US from living abroad had a radicalizing effect from which I never really recovered. On our return to the US this time I had enrolled for a degree in anthropology at Indiana University, the only department that accepted me after my lackluster undergraduate performance. The school had one of the best African Studies programs in the US, however, with old Africa hands from Europe and elsewhere among the visiting faculty. I met a Belgian who had lived through the “independence” of the Belgian Congo. He regaled me with stories of US interference and the CIA orchestrated assassination of its first president, Patrice Lumumba. I joined the campus SDS chapter, a ragtag ‘new left’ group of ‘expatriates’ from the West and East coasts, and was asked to organize its first local antiwar demonstration, on Hiroshima Day. I started writing articles for our chapter newsletter, and for the publication of the SDS national organization. I wanted to bring to the New Left an appreciation of the African decolonization experience and its impact on Black organizations in the US like the Black Panthers.

In a course I took in applied anthropology the teacher described at length his experience attached to a USAID project in Peru that was rebuilding a community after an earthquake. Based on his knowledge of the local Quechuan language and peasant culture, he had warned USAID that everything they built would be of little use to the Peruvian peasants because it was so ignorant of their needs and the environmental challenges of tropical life. USAID built it anyway and the peasants either ignored the results or adapted them to other purposes than what the project leaders had intended. I was impressed with this teacher’s critique and got him to back me in an independent study: an attempt at an ethnography of a low income white community on the edge of town in a low partly swampy hollow full of trailers, shabby dwellings and fundamentalist churches, overshadowed by a couple of smoky electronics factories on higher ground that employed some of the residents. We moved into the neighborhood to better practice ‘participant-observation’ ethnography. Parallel to that project, I engaged some SDS people in a community development project in the same neighborhood. Neither project got very far, but we all discovered the challenges and pitfalls of such endeavors. The white ghetto community mostly treated us like the foreigners that we were in a real sense, and either ripped us off or ignored us. The congregation of the fundamentalist church service that I attended was friendly and welcomed my presence. Otherwise we might as well have been from Africa, or Mars. More naivete lost.

For an easterner like myself, the Midwest working class encountered during the two years in Indiana increasingly confronted us radicals with a wall of indoctrination to the super-patriotism of the official narrative, which it seemed that an antiwar or anti-capitalist movement would continually fail to penetrate. More generally, in the face of a highly successful ability of ruling elites to control the information most of the public receives, I began to be disillusioned with the prospects of raising class consciousness in regard to any national policy goals whatsoever, and started to focus more on the discovery of constituencies disaffected enough to want to build local, alternative institutions, like intentional communities, schools or news media. The academia in which I had planned to make a career came under intense critical scrutiny during the student uprisings of the Sixties, leading me to finally decide to leave it.

Up to the end of the 1960s my radicalism had been mostly limited to a critique of US society, inspired intellectually by the systemic methods of Marxian political economy, and stimulated in practice by the life experiences related above. At that point my critique began to expand, encouraged by an increasingly serious devotion to the study of the science of ecosystems, and by a decision to become a farmer.

Ecosystem science taught me that our species is governed by the same rules of nature as all others, the implications of which for the future of industrial society I began to realize are so momentous that few people have dared contemplate them. Most critical political economy and in fact most conventional social science still fails to fully realize the limitations that nature’s rules impose on the human species.

The decision to become a farmer resulted from my desire to distance my life as much as possible from the mainstream institutions of capitalist society with which I had become disillusioned. It was attractive also because of my familiarity with rural farming life learned as a small child. At that juncture I felt a need to retreat from the US and its problems, and fond memories of the European countryside led to a farming apprenticeship in France. Immersion in the European back-to-the-land movement during those six years provided an education in cooperative projects and their pitfalls.

By our return to the US in 1980, we had acquired enough knowledge to mount a small farming operation that provided both a livelihood and a niche product sufficiently sheltered from the monopoly controlled agricultural economy to allow experiments in agroecological farming methods and systems. My study of ecology guided my farm design. Based on these farming experiences I began to teach in the organic farming movement, which had a limited understanding of ecosystem processes. The US agricultural science community included almost no one trained in systems ecology, and therefore offered the organic movement little guidance. Living withing driving distance of the major agricultural school at Cornell, and more at home in academia than most organic farmers, I gradually fell into the organic movement role of outside agitator at Cornell, where my agroecology was esteemed too radical for most faculty ears.

Eventually, the systemic method of inquiry common to both systems ecology and Marxian political economy led me to take seriously the evidence that the universe is a highly connected entity, one that ‘functions in wholes’ and must be studied and managed as such, or court failure. I thus came to question the whole orientation of the advancement of knowledge since the Enlightenment, whose reductive method that had come to be accepted as “science”. By reducing understanding of causal relations to few variables (following the rule of ceteris paribus), several centuries of scientific inquiry had deliberately ignored the connectedness of the universe in its quest for predictive results. Even more limiting than reductionist science was the discovery that my explorations in the fledgling but growing field of complexity/systems science revealed unambiguous limitations on what any way of doing science can predict, and even what any kind of science can ultimately know about such a highly interconnected universe.

In sum, the worldview arrived at as related by the account in this essay has its ironies. By expanding my questioning of the official narrative, not only about how our society works, and how bound it is by nature’s rules, but even about the limits of knowledge in a complex universe, I have gained a view of the world that is shared by only a tiny minority of humanity, and consequently has little audience apart from that select few. Hence, we are reduced to preaching mostly to that choir. My awareness of the downsides of the habit of critical questioning is not new. After 10 years living in other, mostly Frenching speaking nations, and subsequent multiple trips to Cuba and Mexico armed with a working fluency in Spanish, I have come to realize that in several senses I have become a foreigner in my own country. Such is life, I guess.

Addendum

At some point in the above odyssey I began to write descriptions of the radical changes in my worldview. Here are links to a few of those writings ordered by subject matter, among many to be found on my website. These subjects are all interconnected as I view them, so there will be overlap – some titles appearing in more than one category.

1. Holism vs. reductionism and the compartmentalization of scientific inquiry

Economics as brain damage

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

Through the Looking Glass: Adventures in Landgrant Land

2. Systems thinking and ecological perspective

A systems view of Western policy today

What systems thinking reveals: from biology to political

3. Capitalist social system

What Is the Deep State?

Forces Driving the US Political Economy

The Alchemy of Language in the Pacification of the American People

Locked In: The Paradox of Capitalism

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

A systems view of Western policy today

4. Energy depletion and cost accounting, and the future of industrial civilization

What is Sustainable?

Invisible Ships and Boiling Frogs: The End of Industrial Affluence

Humans Have Energetically Overpowered the Earth

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

Why Trying to Save Industrial Civilization with Alternatives to Fossil Fuels Only Makes Things Worse

Cities and Suburbs in the Energy Descent: Thinking in Scenarios

5. Agrarian futures

Human designs for ecosystem management and survival after the oil era

Food Production Systems in the Decline of the Industrial Age: A Call for a Socio-ecological Synthesis

Through the Looking Glass: Adventures in Landgrant Land

Implications for Agriculture of Peak Cheap Energy

Mass deception and the quest for a more sustainable agriculture

The Peasants Shall Inherit the Earth

Visioning County Food Production – Part One (of a six part series)

Topics: Memoires, Uncategorized | 4 Comments » |

Energy and Sustainability in Late Modern Society

By Karl North | July 9, 2020

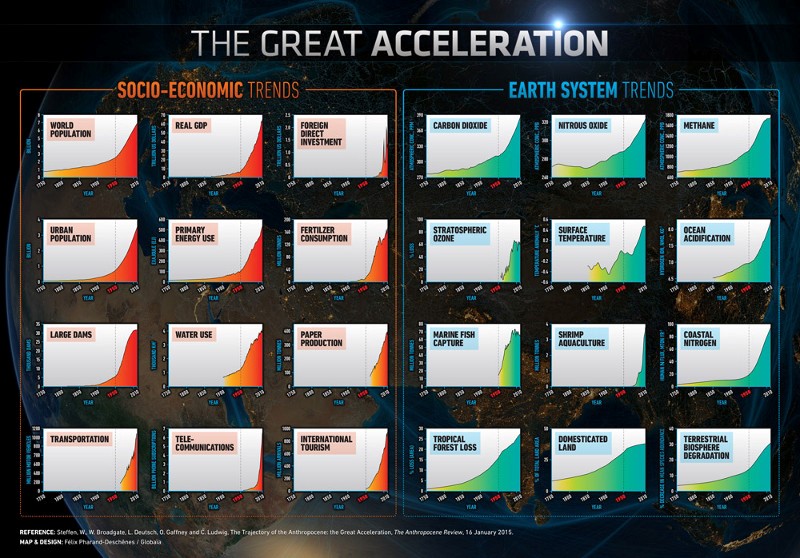

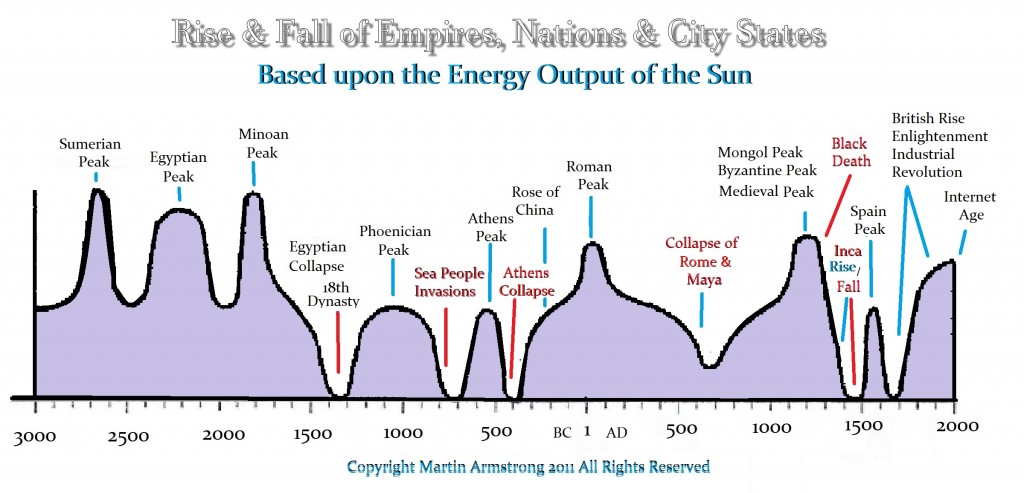

Near the end of the modern age, sustainability assessment of the economic activities of modern society has encountered two problems, one physical, the other cultural. The discovery of a dense, high quality energy source had led to an explosion of human use of the planet’s raw materials and facilitated invention of new technologies, which in turn permitted even greater consumption, in a positive feedback loop. We know this phenomenon as the industrial revolution. Exponential growth in the use of raw materials, including fossil energy, eventually has caused their depletion. In the case of finite materials, this has no solution. In the case of renewables such as topsoil or fossil water, it has led to long-term and sometimes permanent erosion of carrying capacity. This whole dynamic now threatens the existence of modern society.

Also, two centuries of cheap energy have created a global cultural mindset that inhibits a clear understanding of the physical problem. As the low hanging fruit of natural resource consumption essential to sustain the industrial economy has been harvested, we simply throw cheap energy at the problem and consider it solved. Copper ore, for example, now contains only a fraction of the copper it held a century ago. But the result – increasing scarcity of this essential raw material – is palliated by enormously increasing the energy devoted to the mining and processing, so we entertain the illusion that the resource is infinite. Hence, commonly we see no need to evaluate current and future economic activities or technologies in terms of energy or raw materials costs. Only a tiny minority have understood the necessity for such cost accounting and developed the tools to do it properly. This paper will review those tools and discuss their implications for the future of industrial civilization.

As we will see, proper cost accounting requires a systemic perspective that is rare in the modern age. The reductive methods that dominate scientific inquiry deliberately ignore the systemic context of any invention or discovery and promote the illusion that what happens in the laboratory is what will happen in the real world. As a result, systems thinking is uncommon, and further inhibits honest evaluation of the sustainability of human activities.

A review of essential energy concepts

Ecosystem science teaches that human society is a subsystem of a larger ecological whole, and is subject to the same laws. In the language of economics, one could say that human society is a wholly owned subsidiary of nature. This is the premise of everything that follows. Because our schooling includes almost no ecosystem science, whatever lip service exists to this premise is mostly ignored in practice, in how we live our lives.

Nothing happens without energy. Howard T. Odum provided ecosystem science with a rigorous disciplinary basis built around a framework of energy flow, conversion, storages and feedback. By showing that all complex systems follow this energy pattern he developed systems ecology into a general theory that applies to all systems. Odum and his intellectual progeny saw that understanding how energy makes everything happen is so important, not only for the design of durable, healthy ecosystems but for the future of our species and for the future of civilization, that it needed a new term – emergy (that’s with an M): the energy involved in the chain of production of anything.

Emergy is just the full accounting of the energy cost of everything we produce, from the morning cornflakes to fighter bombers to energy itself. Emergy accounting starts with the extraction of raw materials and continues up the production and supply chain to the end product. In an age of dirt-cheap energy, few took an interest in counting up the energy costs of everything. Now, when the energy cost of the fossil energy itself, essential to modern civilization, is permanently rising, it causes energy production, followed by economic activity, to peak and go into permanent decline. That brings to an end the industrial era. Oil geologists, natural resource scientists and systems ecologists have been trying to make the public aware of this for decades, and hit a brick wall of denial.

Here is a key reason emergy accounting is so important. As defined above, emergy is the energy invested in anything produced. The energy return on energy invested (EROEI) is an all-important calculation. It is a critical determinant and constraint on the level of our material standard of living. EROEI is a ratio: energy return/emergy. One can also think of it as net energy: gross energy produced minus emergy. It is simple to understand – it’s like business accounting. If your farm grosses $1 million, that is not profit. If your expense is $1 million, your profit is zero, right?

Now let’s apply EROEI accounting to our situation. Industrial civilization as we know it cannot run without oil. Only oil can power the transportation that is essential to today’s global economy, as Alice Friedemann dramatized in When the Trucks Stop Running and Why You Should Love Trucks. At the height of the oil age in the US 1930s, oil EROEI was 100/1: an energy cost of one barrel of oil for a net energy return of 99 produced and processed. Cheap as water – stick in a pipe and get a gusher. Now it has declined to 11/1 for US conventional oil production and steadily dropping, and less than 4/1 in unconventional oil like hydrofracking. Corn ethanol EROEI is 1/1. That means it adds NO net energy to the economy. The only reason it is produced is subsidies. That is where the global economy is headed as EROEI of all fossil energy sources continues to drop. No more net energy – no more industrial economy.

A group of Odum’s intellectual progeny led by Charles Hall has studied the EROEI of various energy sources, with an emphasis on those claimed to be able to replace fossil fuels. They are finding that the net energy of “renewables” in nations which have devoted serious investment like Germany and Spain is nearly zero, far from the EROEI needed to replace oil’s EROEI of 100/1 in the heyday of the oil consumption that built the industrial economy. In sum, humanity has harvested the low hanging fruit – of fossil energy and most other raw materials necessary to industrial civilization.

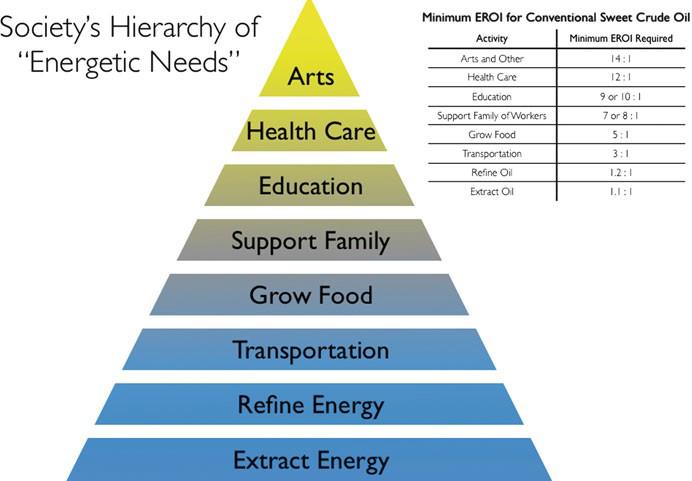

Hall’s group has calculated society’s energy needs as a pyramid of increasing EROI requirements of oil:

Not long into this century, even global oil EROEI will be so low that oil can no longer power any industrial economy, including conventional and most organic agriculture. The energy cost (emergy) of food is huge in our oil age society. Over 90% of that energy cost is fossil fuel, mostly oil. We are eating oil, as it were. For those who pay attention, visible signs have existed since at least 1970 that because of dropping EROEI, the wheels are coming off the US industrial economy. First it began to slow down; now it is shrinking or propped artificially in places (e.g., weapons industry, hydrofracked energy) by cheap credit and enormous debt.

Fully Burdened life cycle accounting

Hall’s group has focused on the fact that every economic activity carries a long tail of energy and material costs. In accounting the costs, systems ecologists find it useful to view our universe as largely composed of open systems, whose inputs and outputs, termed sources and sinks, are governed in part by the laws of thermodynamics. How sustainable the systems are is dependent on how well the inputs and outputs are managed. Natural ecosystems have evolved to cope with source and sink problems (the first law) regarding finite materials on a finite planet, by cycling water and minerals. System survival, even without growth, requires a regular input of energy, just to keep the system from falling apart (entropy, the second law), and approximate a dynamic equilibrium. Natural ecosystems achieve it mainly by harvesting current sunlight, passing it through a food chain. Open systems are heat engines: they use energy inputs to do work, including the work of creating and maintaining organisms, but it must be continually replenished, for in the process the energy is ultimately dissipated as heat, and lost to outer space. As stated earlier, the first lesson of ecosystem science for humanity is that human society is a subsystem of nature, not apart from it, and is therefore subject to the same laws, including the laws of thermodynamics. We need to ask: What are the implications of our subjection to nature’s laws?

Anything a society does requires energy, raw materials and technology (I am defining technology broadly as knowledge to do anything rather than its limited common meaning as some physical manifestation of the knowledge, such as a machine). Lacking any one of these elements, nothing happens. The following thought experiment might help to dramatize this claim.

Suppose that in the year 1800 an angel endowed Benjamin Franklin with all the knowledge he needed to produce a smart phone and its necessary communications infrastructure at the scale of its use in the world today. Nothing would come of this gift of technology because the industrial economy and its energy and raw materials capabilities necessary to the project did not exist.

As with the above thought experiment, most of the problems of sustainability of human activities lie not with the capability of technologies used or proposed, but with the attendant energy and materials costs of applying the technologies in an era of depleting fossil energy caused by the activities themselves. Hence, a full life cycle accounting of environmental costs of any human activity and its technologies is necessary to evaluate the sustainability of an activity. There are two reasons for this necessity.

First, all known alternatives to fossil fuels are diffuse sources that entail enormous energy costs to reconcentrate the energy to approximate the density and quality of fossil fuels, if they are intended to replace them at a significant scale. These energy costs also include sink management problems resulting from outputs that natural systems cannot handle. Negative effects are often long term, such as radiation problems from nuclear power production and silting of reservoirs serving hydropower production.

Second, most arguments ignore that replacements themselves depend on a fully functioning industrial economy which itself is inevitably shrinking due to rising energy costs of energy. As a result, a full energy accounting may reveal many existing or proposed activities or technologies to be unsustainable going forward, or of only limited transitional viability. After two centuries of industrial development based on cheap energy, few proponents of existing or proposed economic activities see the need for such an accounting, or understand what it entails. Hence, at this point, an explanation is in order.

Life cycle assessment (LCA) tracks costs from source activities like mining through a chain of processes to a final product and its disposal. LCA is not new, but the cultural mindset evoked earlier often obstructs a full accounting. Annie Leonard’s Story of Stuff provides a good start on a fuller appreciation of what is missing from the picture and why.

A fully burdened accounting of energy costs of an energy source (EROI), a product or service tracks the LCA of all activities and materials needed to arrive at an end use result. Here are examples of the best such analysis to date, applied to the European projects that are the leading attempts to replace fossil fuels with wind and solar electricity.

In sunny Spain:

Tilting at Windmills, Spain’s disastrous attempt to replace fossil fuels with Solar PV, Part 1

Followed by an update:

Tilting at Windmills, Spain’s disastrous attempt to replace fossil fuels with Solar PV, Part 2

and a slide show of the graphics in this study:

In less sunny northern Europe:

These studies reveal that net energy obtained is close to zero.

Conclusion

Large scale attempts to replace fossil fuel production with alternatives face many challenges, the leading one being the energy costs described in this essay. But fully burdened environmental accounting may be able to identify transitional strategies that incorporate alternative energy at much lower scale.

Apart from the energy costs, the foremost challenges of large scale alternatives are cultural and political. Large scale conversions of the present industrial societies to a different energy source like electricity impose changes of a systemic nature – a multitude of changes that ripple through the system, multiplying costs, which require a period of sacrifice of material standards of living. Historically, societies have accepted such forfeitures only under threat of war. Moreover, the short run profit that motivates economies under private, capitalist control is a major obstacle to such systemic changes. Societies would have to adopt a ‘command economy’ where public policy dictates economic goals, which for generations has been demonized as “communism”.

Also, efficiencies in energy or raw materials consumption that a technology is capable of are real but are subject to the Jeavons effect, whereby savings achieved by efficiencies are spent in increased consumption. This is a normal social response that the growth imperative of the capitalist system and its cultural conditioning to maximize consumption intensifies.

At the other end of the scale, societies have successfully operated on direct solar gain for long historical periods, sometimes with minimal ecological footprint. As an example of a low technology, a water wheel mill that temporarily diverts a short section of a stream multiplies the power of human and animal labor at little environmental cost, compared, say, to a hydropower mega-dam, which comes with a full panoply of inconvenient consequences for society and the rest of nature. As fully burdened environmental accounting becomes more common, it may be able to identify technologies, situated somewhere between these two extremes, that can facilitate the transition to a post-oil age.

One ironic characteristic, but a potential advantage to capitalist systems faced with a transition to a lower energy consumption is its inherent capacity to foster waste, described half a century ago by critics like Vance Packard in his The Waste Makers, and more recently by students of consumerist manufacture of desire like Robert McChesney and Noam Chomsky. Also, the practice inherent in capitalist economies of extracting rent for investment of capital necessitates a growth imperative. And capitalists have found that the best way to maximize profit is to turn natural resources into garbage at the fastest possible rate. Capitalist economies thus create unusual amounts of wasteful and other ‘discretionary’ production that in theory could be eliminated and the liberated energy and raw materials devoted to production that facilitates the transition. For example, conversion of most of the land transportation sector to rail is arguably the single most energy saving transitional policy, usable even after the energy available to move goods by rail is reduced to animal power.

However, in practice even conversions that are more sustainable from an energy accounting perspective face the same political and cultural obstacles as large scale unsustainable ones.

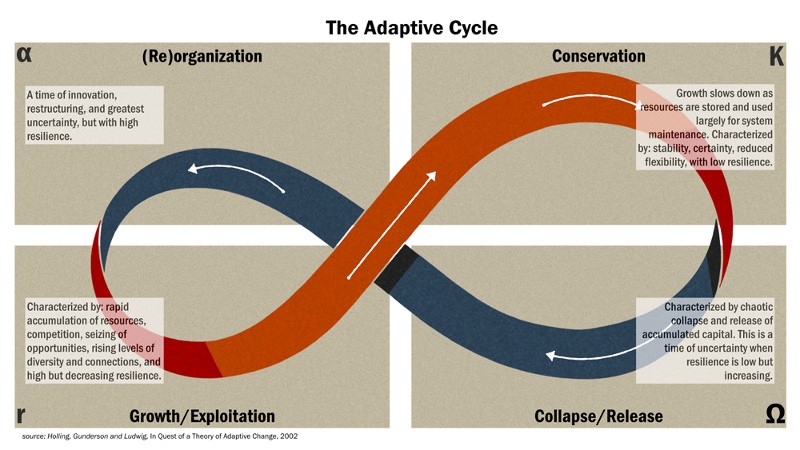

One of the characteristics of complex systems is their resistance to change. In healthy natural ecosystems this can be desirable, and is called resilience. If the resistance is undesirable, we call it inertia. In the present predicament of fossil fueled economies facing loss of their energy source, transitional efforts require such major changes in life styles and skill sets that undesirable inertia is inevitable. Over a decade ago, energy descent writer Richard Heinberg dramatized the problem in his essay, “Fifty Million Farmers”. Where will they be found when most of our urbanized society has neither the skills or the desire?

Topics: Core Ideas, Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

Human designs for ecosystem management and survival after the oil era

By Karl North | January 18, 2020

All societies in history have relied on the land and its plant and animal resources. The superstructure of high technologies and complex forms of social organization like cities that fossil energy has made possible only conceal our essential reliance on the land. As access to the dense, high quality forms of energy in fossil fuels declines, it will force human society to return to modes of land management that use current solar gain and the low energy technologies that it provides[1].

Natural ecosystems offer an excellent guide to the kind of land management that will be necessary, because they run on current solar gain and rely heavily on their internal resource base for inputs. Long before the advent of our species, life self-organized into complexes of species that we now call ecosystems, whose interaction achieved two important synergies:

- They often maximized the carrying capacity of the system – the maximum biomass that the land could support.

- They also achieved a degree of self-regulation via food webs – a matrix of predator-prey and cooperative relationships – that enhanced the sustainability of the whole.

Pre-industrial societies, whether hunter/gatherer, horticultural, pastoral or a combination, learned to benefit from these interactions. Ecosystem science can build on and improve these pre-industrial schemes of land management. Modern knowledge of how ecosystems work can be used to enhance ecosystem processes that are essential to the health and long-term productivity of farms, when they are managed as agroecosystems. This essay will draw on current ecological knowledge to present general design elements and principles of land management to maximize long-term productivity for two types of environments: wet, temperate and relatively dry, seasonal rainfall locations.

These are not the environments that offer the highest potential carrying capacity. Locations where constant irrigation is possible are potentially the most productive, all other things being equal. Early agricultural societies built high “hydraulic” civilizations on rivers like the Nile or the Mekong, on reconfigured wetlands[2], on seasonal floodplains[3], and where high rainfall allowed water capture for wet rice systems[4]. However, they are less common than wet temperate locations such as Eastern North America or Northern Europe, or seasonal rainfall areas like African savannas, dry Asian steppes or the high prairies of Western North America. Hence the focus here; it is these latter two types, lands that most human populations will need to learn to manage sustainably if they are to survive as the industrial era melts away.

Modern systems ecology affords an understanding of how ecosystems function as complex, integrated wholes which, applied to agroecosystem management, shifts the goal from managing to maximize short run outputs to managing for the health of the system. The health of the ecosystem rests in turn on the health of the ecosystem processes: the energy flow, the mineral cycles, the water cycle and the interaction and interdependence of species. Ecosystem science has demonstrated that this holistic approach, while it may involve short run investments that sacrifice output, can improve outputs in the long run and at the same time sustain the system over the long term[5]. The strategy of management for short term outputs instead of the health of the ecosystem bears much of the responsibility for land degradation and the collapse of most civilizations since the advent of agriculture[6]. Systems ecology thus represents a revolution in thinking, a worldview that will inform the agroecosystem designs in this essay.

An essential principle of agroecosystem design in most environments is the integration of animals in relation to other species in the system, especially the plant base. Ecologists call the plant base the primary producers because photosynthesis in plants is the point of entry of solar energy into the ecosystem. That base becomes the source of energy flow in the system throughout the web of its predator-prey and sharing/trading relationships. Hence, strategies that enhance primary producer production raise the production potential and the health of the whole agroecosystem. Grazing animals have many uses, but a central function in design is to use them in a way that maximizes primary producer growth.

An example developed centuries ago is the loose cooperation between nomadic pastoralists and sedentary farmers on the West African savanna and sahel, despite being of different ethnic groups. Fula herders followed the seasonal rains north into the sahel and Sahara. Farmers like Bambara or Malinke allowed the pastoralists to return south in the dry season and settle their livestock on the cultivated fields and fallows of the farmers, gleaning and manuring them, and trading grain for milk.

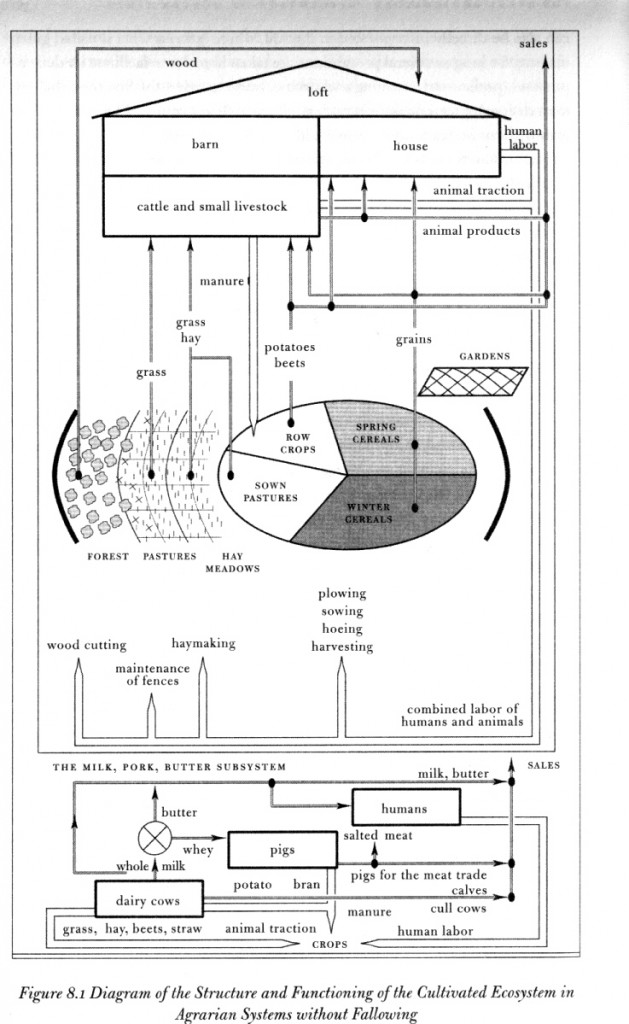

Grazers in wet temperate environments

In many parts of the world, traditional models of agriculture that integrated crops and livestock to various degrees have endured for many centuries in a range of climates. For our purposes, a most interesting improvement on these models developed in areas of Europe that have a cool, wet climate comparable to our situation in the Northeastern US. In their last agricultural revolution before the industrial age, lowland European farmers created a model of animal/crop integrated farming that supported new levels of human population density (see figure)[7]. Previously, a fallow rotation had been necessary to renew fertility, and it supported a few livestock. The revolution consisted of intensive production of perennial and annual forage species for ruminants on the fallow rotation, which in turn allowed higher stocking rates, more barnyard manure, better utilization of pasture manure, and higher fertility and production on the whole farm. Pursued to its limit, this positive feedback loop allows the farmer to maximize the carrying capacity potential of the land.

Enduring examples in other parts of the world of this increasingly tight integration between cultivation and animal husbandry, using different configurations of plants and animals, underscore its advantages, which in the best cases use animals as multi-purpose tools to produce labor, fertility and food.

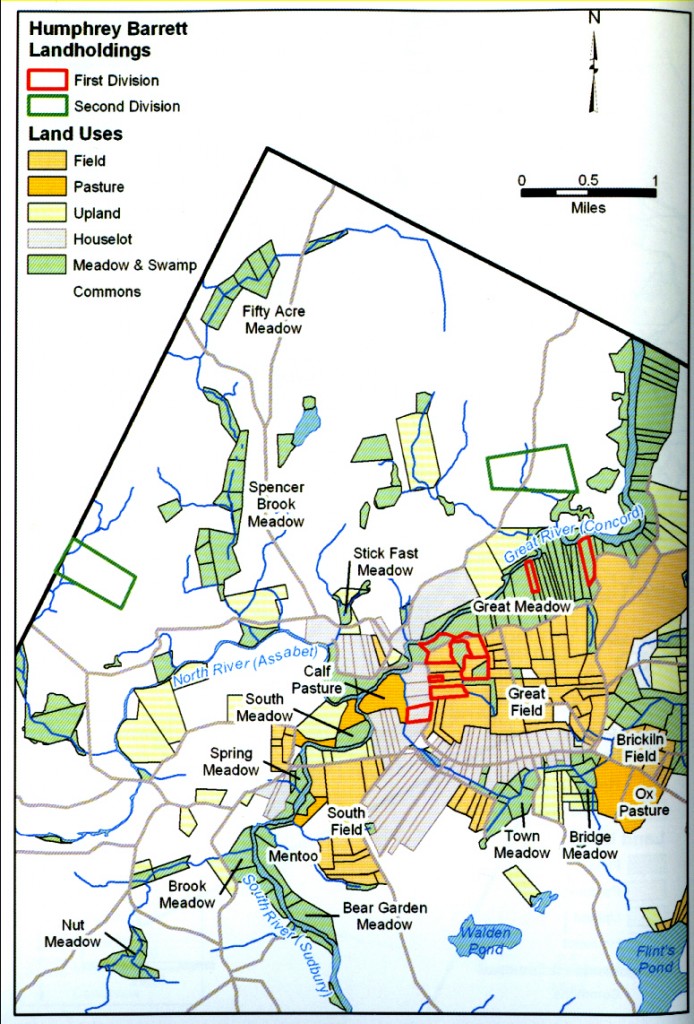

As early as 1650, colonists in New England had adapted animal integrated systems developed in lowland England (Donahue 2004). In colonial Concord, community land use policy supported the needs of an integrated system (see diagram). Riverine flood plain areas were managed as a swamp commons mostly reserved for pasture and hay as they dried out during the growing season. Adjacent fertile land was allocated for cropping, but became a grazing commons after harvest. Upland was multi-purpose, with the higher land maintained in forest. As in parts of Europe, well-watered riverine meadows fed with water-born silt produced enough livestock feed, livestock, and manure to sustain the fertility of land in tillage.

The next major revolution for our purposes was first documented in detail by the French farmer/scientist, André Voisin[8]. High organic matter soils are central to achieving healthy water and mineral cycles, and soils in humid temperate regions are exceptional in their ability to store organic matter and accumulate it over a period of years. Voisin’s book Grass Productivity demonstrated fifty years ago that pulsed grazing on permanent pasture is the fastest soil organic matter building tool that farmers have, at least in temperate climates. Pulsed Grazing is a method of repeated grazing of paddocks in a pasture that controls stock density and timing of stock movement in and out of paddocks to maximize forage production over the growing season. This in turn maximizes manure production to build soil organic matter. Forage plants experience repeated pulses of growth and removal of biomass, both above and below ground, over the growing season. The increase in primary production enhances the carrying capacity of the whole agroecosystem. Its key points:

- Grazing causes forage roots to die back, which adds soil organic matter from the dead root mass. High stock density tramples ungrazed forage into litter that decomposes into soil organic matter.

- Stock enter a paddock before forage growth proceeds from its vegetative stage to seed production, after which growth slows and leaf quality diminishes.

- Stock leave a paddock while there is still sufficient forage leaf area to jump-start regrowth, and uneaten forage has been trampled into litter.

- Stock return to the same paddock when leaf and root regrowth have fully recovered vigor and ability to recover from another grazing, but is still at a vegetative stage of growth.

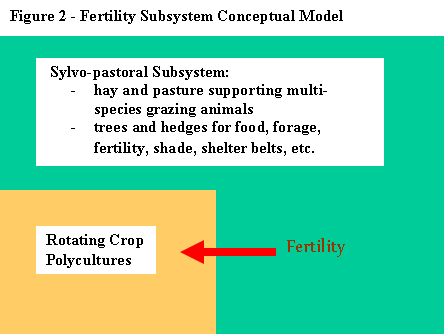

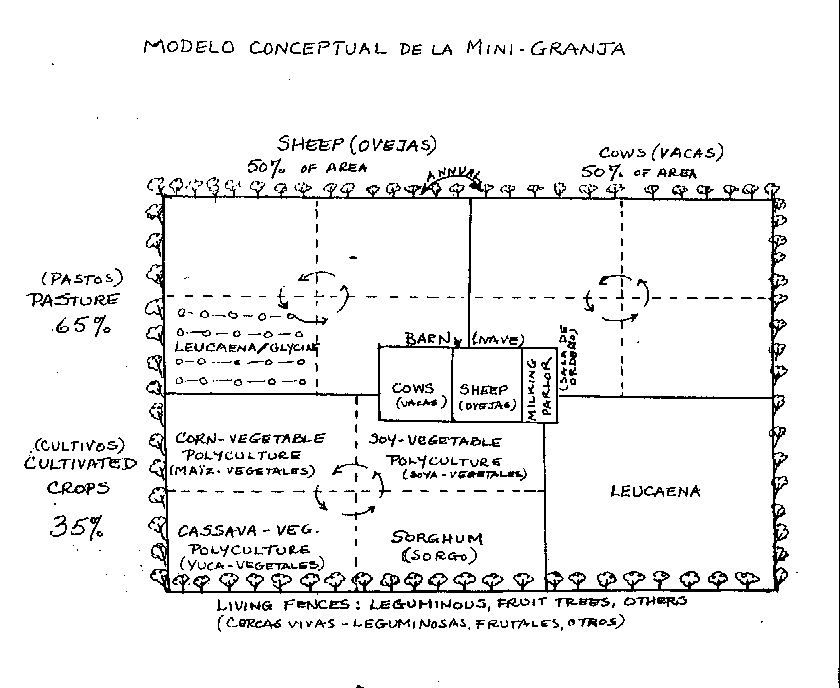

Based on Voisin’s methods, so called ‘rotational grazing’ methods have spread among farmers in the US organic farming movement, but few have grasped the holistic nature and importance of Voisin’s work – to make intensively managed grazing the driving core of a crop/livestock agroecosystem that is highly productive with minimal external inputs. A notable exception is the group of Cuban agroecologists who came to the rescue of Cuban agriculture in 1989 when it lost access to the imports that its essentially high-input agriculture required. Building on Voisin’s thesis, their research showed that a system with roughly 3 acres of intensively managed forage land will both sustain itself in fertility and provide a surplus of fertility via vermicomposted manure to sustain roughly 1 acre of cultivated crops (Figure 2).

The following diagram shows a conceptual model that we developed with Cuban scientists to improve their original cow-based system by including multi-species grazing. The idea was to create a self-sufficient core system that would support a variety of subsidiary crop and animal production.

Like the Cubans, we operated Northland Sheep Dairy in upstate New York using insights from Voisin’s research; we designed our farm agroecosystem to adapt and improve on the natural grass-ruminant ecosystems that helped create the deep topsoils of Midwestern North America. Details of our design appear in earlier publications, but in summary the design focus is on three areas that are crucial to manage to maximize tight nutrient cycling. Key points of the farm nutrient cycle:

- Pasture management for a synergistic combination of productive, palatable perennial forages, kept in a vegetative state via high density, pulsed grazing throughout the growing season to maximize biomass production;

- Manure storage in a deep litter bedding pack under cover during the cold season to maximize nutrient retention and livestock health;

- Vermicomposting the bedding pack at a proper C/N (carbon/nitrogen) ratio during the warm season to maximize organic matter production, nutrient stabilization and retention, and spreading the compost during the warm season as well, to maximize efficient nutrient recycling to the soil.

This design is working well on our farm and confirms Voisin’s thesis: in a few years forage production tripled on land previously abused and worn out from industrial methods of agriculture, and soil organic matter is slowly improving.

The weakest link in the mineral cycle at this point is the losses to leaching in our wet climate. Our solution was to design a sylvo-pastoral model for the Northeast: forage fields that will incorporate enough trees and other deep rooted plants to partially patch the leaching leak in the mineral cycle, still serve the other functions of the field (high quality hay and intensively managed pasture), and even capture synergies (shade, nitrogen fixing, forage diversification) to make the system more productive and healthy than forest and pasture separately[9]. We have seen such systems working well in Cuba, for orchard or timber production in pastures surrounded as well by live legume fence posts coppiced for forage.

Our overall design goal for the farm is to maximize productivity while respecting ecological imperatives by making the biological and physical resources of the farm serve multiple functions, as they often do in unmanaged ecosystems that self-organized in the course of natural history. In this effort we look for opportunities for symbiosis, to capture synergies. The goal is to avoid external inputs and find inputs in the agroecosystem itself. Like the historical models already evoked, we make significant use of draft animal power, which presents new opportunities to use animals as tools to provide ecological services. Our horses and mules add to the fertilizer production of the sheep flock, and used in multi-species grazing they allow more efficient use of pasture and better parasite control: they complement the sheep with different grazing habits, and their different internal parasites diminish the effective pasture parasite load for the sheep.

Grazers in seasonal rainfall environments

Large areas of the planet are relatively dry environments with seasonal rainfall. Range ecologist Alan Savory, while managing wild and domestic livestock on these lands in Southern Africa, observed that the land was degrading despite reductions in the stocking rate, and removing the grazers completely made the situation worse. His research from studying the dynamics of natural, unmanaged grassland ecosystems showed that predation on large herbivore species shapes their grazing movement and is essential to the health of these types of ecosystems[10]. Not only is timing of herd movement critical, as Voisin had shown for wet, temperate environments, but frequent bunching of herds in response to predator pressure is critical to maintain seasonal rainfall ecosystems. If predator populations are insufficient or absent, human grazing management must simulate the natural impact of predators on the herd.

In these dry environments, ungrazed grasses remain on the stalk for long periods and oxidize, breaking the mineral cycle back to the earth, inhibiting grass regrowth and shading other plants. Lacking litter, bare ground remains unprotected from the sun’s drying effect, and capping of the soil surface reduces rain absorption, both of which weaken the water cycle. The deterioration of these essential ecosystem processes degrades the grassland ecosystem as a whole, grass production declines and bare ground between plants increases.

High density grazing with frequent herd movements solves these problems. The bunched herd tramples uneaten forage and undesirable woody plants, creates litter, and its hooves break the capping of the soil surface. The bunched herd grinds litter and concentrated manure into the earth where it can begin to decompose back to soil organic matter. The soil begins to hold more water, repairing the water cycle. The trampling sacrifices of some of the forage in the short run, but sustains and rebuilds the health of the grassland ecosystem overall, increasing grass productivity and stocking rate (carrying capacity) in the long run. This human management strategy mimics the historically evolved dynamics of natural grassland ecosystems, which include a sufficient population of predators on large herbivores.

In sum, as Savory has demonstrated in the US West, South Africa and elsewhere, seasonal rainfall grassland ecosystems degrade with the wrong kind of management of large herbivores, often either by overgrazing or too much rest. He showed that they revive as patches grazed at high stock density spring back to life. Using this holistic approach to management, ranchers and farmers have brought large tracts of rangeland back to normal productivity. As productivity builds, the land can carry a higher stocking rate, which in turn presents opportunities for more beneficial herd effect from high density grazing, setting up a positive feedback loop.

Conclusion

Resource depletion and attendant damage to essential ecological services like clean water and fertile soil are sending industrial civilization into catabolic collapse. This process will eventually force human society, if it is to survive, into a subsistence economy that manages for ecosystem health, not short run output. Agroecosystems will need to be highly input self-sufficient. Hopefully the insights from agroecology described in this paper will facilitate the transition to a future without fossil fuels.

[1] The Industrial Economy is Ending Forever: an Energy Explanation for Agriculturists and Everyone

Kunstler, James Howard. 2005. The Long Emergency

[2] http://www.chinampas.info/, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinampa, Ancient Mayan Water Control Systems

[3] Donahue, Brian. 2004. The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord.

[4] King, F. H.(Franklin Hiram), Book Farmers of forty centuries; or, Permanent agriculture in China, Korea and Japan.

[5] Allen, T.F.H., Joseph A. Tainter, Thomas W. Hockstra. 2003. Supply-side sustainability

[6] ibid

[7] Mazoyer, Marcel, and Lawrence Roudart. 2006. A History of World Agriculture: from the Neolithic age to the current crisis. Monthly Review Press, New York.

[8] Voisin, André. 1959. Grass Productivity. Philosophical Library, New York. Island Press Edtition, 1988.

[9] North, Karl. 2008. Optimizing Nutrient Cycles with Trees in Pasture Fields. LEISA Magazine, 24 (2), March 2008.

[10] Savory, Alan. 1999. Holistic Management: A New Framework for Decision Making.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Core Ideas, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

A systems view of Western policy today

By Karl North | July 12, 2019

Complex systems are resilient, or resistant to change from another viewpoint. Human societies are complex systems. Historically they have exhibited this inertia – a tendency to repeatedly snap back to business as usual or some facsimile of it when faced with a long period of inevitable change. Modern industrial society confronts just this situation – a long period of deindustrialization due to declining access to essential raw materials and damage to indispensable ecosystem processes.[1] Inertia in human society has multiple sources: political-economic, social and cultural. In this essay I will explore the political economy or general structure of power that shapes the policies of Western nations as a basis for better understanding how it will react to the long emergency. To better tackle the subject, a summary of the systems worldview will be useful.

A holistic or systems view of the universe holds that there are behaviors of wholes that are not predictable from the behaviors of the parts. That is, one cannot simply add up the behaviors of the parts and achieve an understanding of the whole. Missing from that analysis are emergent behaviors, so-called because they can be explained only by a study of the whole. Emergent behaviors are the result of what we call synergies, themselves the product of the web of interaction of multiple variables in the whole. A corollary of the core systems principle is that that the causes of the behavior of wholes are often multiple. A crowning lesson from systems science is that many behaviors of wholes are not predictable at all, while some are predictable in their rough shape over time only because they are driven by ecological imperatives, themselves obedient to the laws of energy and matter.

This worldview is still relatively rare, even actively resisted (more inertia), so that when we try to understand a complex whole such as foreign policy behavior patterns of the Western world in recent decades, we miss the synergies. What is worse, after several centuries of technological achievements, few denizens of the modern age are willing to accept the limits of scientific understanding described above. Instead of considering the whole social system and its power structure, we fix on parts. In the example that is the subject of this essay, many attempts to explain foreign and even some domestic policies of Western governments fix attention on a single source of the power that shapes policy, whereas I propose that policy is shaped by a synergistic alliance of three power sources. I will first summarize each of these most common explanations.

- Military industrial complexes (MICs), bolstered by their increasing role in propping up weakening Western economies, promote serial wars to serve their goal, which is ultimately to maximize the profits of their weapons industries. Over time, a part of the military high command in each nation is corrupted, lured by payoffs from the weapons industry and the opportunities for career advancement that wars offer, and the promise of lucrative retirement positions in the industry. Hence, the military high command multiplies demands for exotic war materiel and conforms to what serves the industry rather than what kind of weaponry best serves the defense of the nation. Cost overruns abound and quality of products declines, overloaded with expensive, unwieldly technology. The MIC encourages inter-service competition (boats for the Army, planes for the Navy, etc.) to bloat defense budgets.

- The Zionist fifth columns[2] in most Western nations, backed by disproportionate Jewish wealth and clannish organizational power, have grown over the 70 years of the existence of Israel to serve as a tail wagging the dog of national governments that bends policies to serve Israeli interests. As an example, a shrewd Zionist pattern of campaign contributions to both major political parties in the US has assured almost total congressional loyalty to Israeli interests. Zionists including Israeli dual citizens hold unusual numbers of high government positions and ownership of mass media. They stifle criticism with threats of accusation of anti-Semitism and increasingly with laws that criminalize anti-Semitism and even criticism of Israel. In the US, the large population of Christian evangelicals serve as willing foot soldiers for Israel in the electorate.

- A global hegemonist faction centered in the intelligence establishments is devoted to opening and maintaining the whole world’s economies to the unhindered penetration of transnational private capital. Published government documents that the general public rarely reads describe a geopolitical strategy for achieving worldwide hegemony. The CIA in conjunction with secret services of other Western nations maintains a permanent presence in all countries running a variety of clandestine operations aimed at providing support for compliant client regimes and overthrowing those that attempt to declare independence from Western imperial control. This permanent policy of interference in the affairs of foreign nations by officially sanctioned institutions of Western governments violates international law, the UN charter, and in most cases national constitutional law. Because its effect has been to destroy trust in Western diplomacy, a small but steady stream of renegades from the CIA has exposed its history of covert operations around the world, begun as early as L. Fletcher Prouty’s The Secret Team,[3] published in 1973. It is a work of massive detail based on Prouty’s key role as a CIA briefer to shape intelligence input to the National Security Council policy formation process during the war in Vietnam. The book quickly went through three editions, then mysteriously disappeared from commercial markets and even libraries, but Prouty has published recent editions updated with accounts of CIA operations since the original publication. These accounts reveal an organization dedicated to organized crime like any other mafia, except that it enjoys the cover of legitimacy as a permanent part of US government.

A systems view reveals that single causes are rare in complex systems. My thesis is that by themselves no one of the forces outlined above fully explains Western policy trends in the last half century. A critical view free of influence from establishment narratives (themselves often a CIA product) easily shows that most of these policy patterns fail to serve the welfare of the citizens of Western nations; while protecting and promoting the interests of private capital they actually impair the security and welfare of Western societies. Most countries invaded or at risk for invasion from Western “coalitions of the willing” posed no risk to the national security of the peoples of Western nations. Western “wars on terror” are actually state-sponsored terrorism that cause suffering numbering in the hundreds of thousands in foreign places – all out of proportion to the suffering and security risk of “terror” to domestic society – and worse, actually generate counter-terrorism. Taxation to support expensive “defense” establishments is contributing to the decline of standards of living in Western nations. Full bore global imperial pressure necessitates demonization of nuclear powers like China and Russia, which strains relationships and brings the risk of nuclear war closer. The penetration of Western-based transnational capital destroys Third World economies and often requires destabilization and overthrow of governments, all of which sends waves of unwanted immigrants into Western societies. Policies so contrary to true interests of citizens of Western nations necessitate the domestic manufacture of fear, justifying and enabling the creation of surveillance states and the suppression of dissent.

So, who does benefit from all this? In my view, what best explains Western policy patterns is that the tail wagging the policy dog is not one of the sources of power and influence listed above but an alliance, sometimes close, sometimes loose, between all three, based on a strong overlap of interests and goals. As with any successful alliance, the whole is more powerful than the sum of the parts because each partner is willing to serve the interests of the others as long as its own goals are respected.

The coincidence of goals is most obvious in the foreign policies of Western governments regarding the societies in the Middle East. The MICs are on board for wars anywhere, so they are happy to support the Zionists in their quest to provoke the West into wars against their enemies in the Muslim world. These wars also fit well with the long-term project of global hegemonists – to fully control Russia and China for the penetration of international capital. They have been using Islamic extremists as proxies to stir up Muslim populations and destabilize the soft underbellies of these nations ever since they armed Osama bin Laden against Russia’s erstwhile ally Afghanistan during the Carter administration. So the use of these militants as proxies in the wars in the Middle East have provided opportunities to breed, train and develop the potential of extremist militias for deployment anywhere in the Muslim world, Muslim populations in the Russian Federation and China in particular.