« Energy and Sustainability in Late Modern Society | Home | The Orange Revolution Comes Home to Roost? »

The Making of a Radical Worldview

By Karl North | July 20, 2020

Recently I was contacted by someone who had been drawn into the life of the alternative high school, Rochester Educational Alternatives, an experiment I attempted during our time in Rochester. A conversation ensued in which he wondered what in my background was responsible for my decision to create a radical alternative to public schooling. This slice of autobiography was my answer.

At about age 16-18 I began to question what I call the official narrative about how our society works – a narrative that comes all our lives in an endless flood from US leaders, mainstream media and most school education right up through doctoral level degree programs, especially in sensitive fields like economics, political science and history. For me, first questions revealed myths, generated more questions and revealed more myths in a domino effect. Spurred by experiences that I will describe in this essay, my disillusionment with the official narrative suffered exponential growth. Not immediately clear was why this occurred in my case, and so rarely in others. My parents were scientists, apparently vaguely liberal, and rarely talked politics or social issues.

However, although I did not reflect on it until much later, my early childhood was unusual, partly due to deliberate parental choices. They were outdoors people in their free time, gardeners and tent campers, and unlike most of their professional class, elected to raise their children on a farm as the best chance of a healthy upbringing. In those war years they rented the ageing Victorian farmhouse on a working farm in New Jersey that produced a rotation of potatoes, wheat and alfalfa, managed and worked completely by a black farmer who was paid a pittance by the absent property owner and had to work with dilapidated machinery. South Jersey at that time was Dixieland. This black farm manager and his family lived in a shack with no plumbing or electricity behind the farm buildings. I followed him around everywhere as a 6-12-year-old, and he indulged my interest in all the exciting farm activities, letting me ride the machinery. He deliberately taught me things like how to cut seed potatoes properly, and a quick trick to tie off a sack of wheat or potatoes, and inadvertently taught me about living while black. As far as I know, I was the only white person to spend time with his family in their shack. He was my closest adult friend beyond my parents.

My parents were frugal New Englanders and did not go for the frills their income could have provided us, but we enjoyed some version of the upper middle-class standard of living. Hence the contrast between our farmhouse and the shack out back was stark, but I had no framework for understanding it for many years, not from my parents or school teachers or anyone else. The closest neighboring children my age were poor or working-class whites. The farm across the road produced that same crops with good machinery but were prosperous and wintered in Florida. I followed their teenager in his chores: milking the family cow, feeding their handful of pigs, collecting eggs for a side business for sale to us and the nearest general store. He and his older sister had riding horses. I think this unusual environment in early life began to color, much later, how I saw the world in later life.

My parents taught me how physical and biological things worked, and enough reading and numbers to feed my interest in building and growing things. As little of that hands-on activity was offered in school, I did well grade-wise and the school once considered having me skip a grade, but I quickly got bored. “Karl spends class time looking out the window” was the first-grade teacher’s explanation for flunking me in “citizenship” on my report card. I began to get a dim view of formal schooling. I was sustained in school luckily by excellent music teachers right up through high school.

Starting in my last year in high school, a series of experiences began to deepen my educational disillusionment and changed my perspective on US society. My father was given a sabbatical year off and decided to spend it interacting with colleagues in his field in Germany. The whole family went to Europe to take advantage of the experience. I spent the year as a boarding student at the Ecole Internationale de Genève. Joe Dassin, later to become a famous French pop singer, lived across the hall. The McCarthy witch hunts had destroyed his father Jules’ successful US career as a film maker, and the family moved to France where his films as a US expatriate made him famous again. In my ignorance of both US politics and European culture, I knew nothing of Joe’s family history until much later. We were both musically inclined, however, and created a quartet that performed black spirituals at a school event. An Ecolint tradition was to organize a mock UN session, for which the Geneva UN conference hall and its language translators were put at our disposal. Students each chose to represent a particular country. Joe captured the coveted role of Soviet representative, and played the role to the hilt.

Another innovative tradition at Ecolint was a kind of scavenger hunt competition. It sent teams of senior boys on their own with a small budget and a free rail pass all over Switzerland, solving problems set to us by the organizers at each stop to gain intelligence on where to go next. Joe, the cosmopolitan European, was disgusted to find himself teamed up with three naïve Americans including myself, but I learned a lot from him as we traveled together. The breadth of perspective and self-confidence achieved in those four days was dramatic, one that I have always tried to reproduce in designing learning projects as a teacher. That event is an example of the capacity for independent action and self-motivation expected of secondary and college age students in Europe, very different from the ‘in loco parentis’ approach common in the US.

Another example of the European approach that became a major learning event for me was the school’s decision on what to do with a few students like me left at school during spring vacation, when parents had signed up most students for expensive group tours. The school asked an Ecolint alumnus who was attending Geneva University to design a low-cost vacation for the remnant. His plan, which the school administration accepted without hesitation, was to lead the half dozen students, all from different national backgrounds and some barely acquainted with one another, on a walking tour around the coast of Corsica, camping out along the way on beaches or in barns in case of rain, and eating bread, cheese and other foods we might purchase in villages and from local peasant farmers. Like the scavenger hunt, this trip was a highly memorable experience. It put me in constant contact with another rural European landscape and people in a beautiful Mediterranean setting, and a wonderful daily group learning challenge in a deliberately unstructured way.

I came away from that year highly impressed with the much longer historical depth of European society and culture, evident in its landscapes and centuries-old architecture, and in its approach to education, compared to the US. I was intent on returning to Europe as soon as possible for more learning from living in foreign places.

My undergraduate years were marked by two interruptions that gradually made me a critic of what was called the ‘liberal arts education’. I came to view it as a smorgasbord taught by specialists who mostly had not the breadth of enough general education to help students connect the dots into the holistic approach that I was beginning to see was a necessary tool for learning about the world and navigating intelligently through life.

The first interruption came at the end of my freshman year when a combination of poor course counseling, a broken leg in a skiing accident and my own misjudgment of my intellecual talents led the school to require a leave of absence to gain a better grip on my educational goals. At that point all I wanted to do was return to Europe, but was not enterprising enough to find a way to support myself. Instead, because by leaving college I automatically became eligible for the draft, I was pressured into volunteering for two years in the army. This turned into a major educational event, for I was thrown in daily association with the very lower class with whom I had lived my early childhood, but had been separated from in college tracking in secondary school, and in the prestigious liberal arts college itself, full of students from affluent classes. Moreover, of the three radio operators in our unit beside myself, the black one was by far the best, reputed to be the fastest Morse code guy in the regiment. He was the first black person I had contact with since early childhood, and became friends despite the racial tensions kept barely under control by the army discipline and regimentation. One time he and I were asked to take a jeep to the regimental field camp deep into the state of Virginia, a hundred miles south of the main army base in Maryland. I was still so naïve that when we stopped at a restaurant for lunch he laughed when I asked why he refused to enter. We were traveling in Dixieland in 1959 – and in restaurants, no niggers allowed.

Because of my unusual childhood, I discovered that blacks sensed that I was approachable, at least enough to be engaged in conversation. The other black in our communications platoon, who inhabited a neighboring cubicle in the dormitory, liked to tell me about his career strategy for moving up in the service, and leaving ghetto life behind. He had invested in tailored versions of army fatigues or work clothes, starched laundering, and had become the spiffiest dresser in the platoon, with boots spit-shined like mirrors.

I was a good radio operator but a lackadaisical soldier, and the army was so relieved that the end of my service approached that they let me out a month early “to readapt to college life”. Actually, after two years of rubbing shoulders with a class of people for whom army life was an improvement, the general run of students back in my prestigious liberal arts college struck me as incredibly insensible to how most of the world lives.

I now had a better plan for weathering higher education, this time with an interruption of my own design. I had taken courses in French Literature and European history in the army, and was the only French major who spoke passable French, with which I persuaded the department and Wesleyan University to let me enter a Junior year in Paris program, for credit.

Meanwhile as a sophomore I had discovered Norman O. Brown, later to emerge for some as a sixties counter-culture hero, and perhaps the only transdisciplinary polymath on the faculty. He had sallied forth from his obscure position in the classics department to teach a course that delivered a resounding critique of Western Civilization, bringing to bear history, Marxian political economy, Freudian depth psychology, anthropology, and of course Greco-Roman classical literature and mythology, a course based on his most well-known book, Life Against Death. Loathed by all the faculty whose fields he had invaded, he eventually left for Berkeley, and thence to Rochester University, where I reconnected with him as an anthropology graduate student there, and sat in on his course (again).

The Paris of 1960 was perfect for the making of a US radical. The culture available ranged from Lolita and Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the bookstalls by the Seine to large academic bookstores devoted to leftist literature, to a broad spectrum of journalism unknown in the United States. One eye opener was that the European editions of even Time and Newsweek were markedly different from the US editions my parents subscribed to back home. The tone and substance in the latter generally conformed to the values and beliefs of the official narrative, a set of fairy tales that most Americans who lived in foreign countries for any length of time would no longer swallow.

I enrolled in a course on Marx at the Institute des Sciences Politiques. The French colonies were declaring independence, Algeria was winning its war of liberation, and that fall an alliance of students and labor unions organized a huge demonstration in Paris for Algerian independence. The demonstration was brutally crushed by the Paris police whose head had been a Nazi collaborator during the war. The De Gaulle government had declared in favor of Algerian independence, so the right-wing army officer faction leading the fight in Algeria to keep it French threatened to overthrow the French government. Every morning for a while I walked past machine gun emplacements at street corners, to protect the prime minister’s residence, whose back garden opened on the block where I lived.

I was fluent in French, but the Sorbonne was overrun with foreign students, so the French students mostly ignored us. Instead I found French acquaintances in low income retail workers who lunched by the Seine on nice days – midinettes they were called. One invited me to fancy Sunday dinner with her family. They got me drunk on many different wines and took me on a tour of the palace of Versailles. A gay French arts student once tried to pick me up, but eventually gave up and introduced me to a female friend of his, also a student at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. They got me accepted at the student restaurant at their school, a rollicking place with better food than the gloomy student restaurant I had been assigned to as a foreigner. In the Spring I met an unemployed film crew worker from Avignon. We hitched a produce truck heading back south at midnight from the main Paris Market, borrowed his brother’s Lambretta in Avignon, and rode on it through Spain for a month living on a shoestring, staying mostly in youth hostels or beaches. Hitch hiking back from Avignon after the trip, I traveled with a nun for the whole two-day ride to Paris. At night she dropped me off at the local youth hostel and picked me up in the morning.

By the time I returned to the US from France, I saw a senior year in college as a distinct anticlimax, an ordeal to be endured. My fiancé and I already had decided to seek a teaching job in Africa that avoided the Peace Corps. My regular college work suffered because my time was taken with studying African affairs at night with a visiting professor for no credit, because the college did not offer such courses. I almost flunked out (again) because I failed to finish an assigned paper for an independent study course, run by the only other Marxist on the faculty, an old guy hidden away in the French department. It was actually an interesting project, studying the Paris Commune of 1870 via one of its newspapers, but my focus of study had already become Africa. I had learned that the better one is prepared for living in a foreign society, the deeper the experience.

By the time we reached our jobs teaching secondary school English as a foreign language in the left-leaning Republique du Mali, I was conversant enough with French culture and with the political economy of the decolonization process in which we were immersed to make the two years in Africa a valuable learning process. Occasional close encounters with the US diplomatic community in Mali sharpened my critique of US foreign policy. The bloated staff running a small USAID program made the Malians suspicious that they were all CIA. So, the Malians banned all unchaperoned US diplomatic community travel beyond the capital city and closed down the USIA library. As employees of the Malian Ministry of Education, Jane and I were almost the only Americans who had the run of the country. On breaks from teaching we visited Malian teachers we had met in a summer intensive language program and the family homes of our students, who came from all over the country as far as Timbuktu. We explored other countries in West Africa. On close inspection I saw most formal political decolonization as a cover for continuation of the previous colonial economy and its pillage. Once a USAID guy I did not know learned of our travels, invited us to dinner and tried to interrogate us.

The culture shock of every return to the US from living abroad had a radicalizing effect from which I never really recovered. On our return to the US this time I had enrolled for a degree in anthropology at Indiana University, the only department that accepted me after my lackluster undergraduate performance. The school had one of the best African Studies programs in the US, however, with old Africa hands from Europe and elsewhere among the visiting faculty. I met a Belgian who had lived through the “independence” of the Belgian Congo. He regaled me with stories of US interference and the CIA orchestrated assassination of its first president, Patrice Lumumba. I joined the campus SDS chapter, a ragtag ‘new left’ group of ‘expatriates’ from the West and East coasts, and was asked to organize its first local antiwar demonstration, on Hiroshima Day. I started writing articles for our chapter newsletter, and for the publication of the SDS national organization. I wanted to bring to the New Left an appreciation of the African decolonization experience and its impact on Black organizations in the US like the Black Panthers.

In a course I took in applied anthropology the teacher described at length his experience attached to a USAID project in Peru that was rebuilding a community after an earthquake. Based on his knowledge of the local Quechuan language and peasant culture, he had warned USAID that everything they built would be of little use to the Peruvian peasants because it was so ignorant of their needs and the environmental challenges of tropical life. USAID built it anyway and the peasants either ignored the results or adapted them to other purposes than what the project leaders had intended. I was impressed with this teacher’s critique and got him to back me in an independent study: an attempt at an ethnography of a low income white community on the edge of town in a low partly swampy hollow full of trailers, shabby dwellings and fundamentalist churches, overshadowed by a couple of smoky electronics factories on higher ground that employed some of the residents. We moved into the neighborhood to better practice ‘participant-observation’ ethnography. Parallel to that project, I engaged some SDS people in a community development project in the same neighborhood. Neither project got very far, but we all discovered the challenges and pitfalls of such endeavors. The white ghetto community mostly treated us like the foreigners that we were in a real sense, and either ripped us off or ignored us. The congregation of the fundamentalist church service that I attended was friendly and welcomed my presence. Otherwise we might as well have been from Africa, or Mars. More naivete lost.

For an easterner like myself, the Midwest working class encountered during the two years in Indiana increasingly confronted us radicals with a wall of indoctrination to the super-patriotism of the official narrative, which it seemed that an antiwar or anti-capitalist movement would continually fail to penetrate. More generally, in the face of a highly successful ability of ruling elites to control the information most of the public receives, I began to be disillusioned with the prospects of raising class consciousness in regard to any national policy goals whatsoever, and started to focus more on the discovery of constituencies disaffected enough to want to build local, alternative institutions, like intentional communities, schools or news media. The academia in which I had planned to make a career came under intense critical scrutiny during the student uprisings of the Sixties, leading me to finally decide to leave it.

Up to the end of the 1960s my radicalism had been mostly limited to a critique of US society, inspired intellectually by the systemic methods of Marxian political economy, and stimulated in practice by the life experiences related above. At that point my critique began to expand, encouraged by an increasingly serious devotion to the study of the science of ecosystems, and by a decision to become a farmer.

Ecosystem science taught me that our species is governed by the same rules of nature as all others, the implications of which for the future of industrial society I began to realize are so momentous that few people have dared contemplate them. Most critical political economy and in fact most conventional social science still fails to fully realize the limitations that nature’s rules impose on the human species.

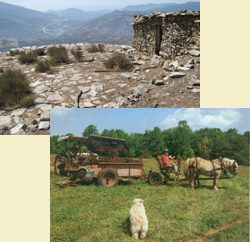

The decision to become a farmer resulted from my desire to distance my life as much as possible from the mainstream institutions of capitalist society with which I had become disillusioned. It was attractive also because of my familiarity with rural farming life learned as a small child. At that juncture I felt a need to retreat from the US and its problems, and fond memories of the European countryside led to a farming apprenticeship in France. Immersion in the European back-to-the-land movement during those six years provided an education in cooperative projects and their pitfalls.

By our return to the US in 1980, we had acquired enough knowledge to mount a small farming operation that provided both a livelihood and a niche product sufficiently sheltered from the monopoly controlled agricultural economy to allow experiments in agroecological farming methods and systems. My study of ecology guided my farm design. Based on these farming experiences I began to teach in the organic farming movement, which had a limited understanding of ecosystem processes. The US agricultural science community included almost no one trained in systems ecology, and therefore offered the organic movement little guidance. Living withing driving distance of the major agricultural school at Cornell, and more at home in academia than most organic farmers, I gradually fell into the organic movement role of outside agitator at Cornell, where my agroecology was esteemed too radical for most faculty ears.

Eventually, the systemic method of inquiry common to both systems ecology and Marxian political economy led me to take seriously the evidence that the universe is a highly connected entity, one that ‘functions in wholes’ and must be studied and managed as such, or court failure. I thus came to question the whole orientation of the advancement of knowledge since the Enlightenment, whose reductive method that had come to be accepted as “science”. By reducing understanding of causal relations to few variables (following the rule of ceteris paribus), several centuries of scientific inquiry had deliberately ignored the connectedness of the universe in its quest for predictive results. Even more limiting than reductionist science was the discovery that my explorations in the fledgling but growing field of complexity/systems science revealed unambiguous limitations on what any way of doing science can predict, and even what any kind of science can ultimately know about such a highly interconnected universe.

In sum, the worldview arrived at as related by the account in this essay has its ironies. By expanding my questioning of the official narrative, not only about how our society works, and how bound it is by nature’s rules, but even about the limits of knowledge in a complex universe, I have gained a view of the world that is shared by only a tiny minority of humanity, and consequently has little audience apart from that select few. Hence, we are reduced to preaching mostly to that choir. My awareness of the downsides of the habit of critical questioning is not new. After 10 years living in other, mostly Frenching speaking nations, and subsequent multiple trips to Cuba and Mexico armed with a working fluency in Spanish, I have come to realize that in several senses I have become a foreigner in my own country. Such is life, I guess.

Addendum

At some point in the above odyssey I began to write descriptions of the radical changes in my worldview. Here are links to a few of those writings ordered by subject matter, among many to be found on my website. These subjects are all interconnected as I view them, so there will be overlap – some titles appearing in more than one category.

1. Holism vs. reductionism and the compartmentalization of scientific inquiry

Economics as brain damage

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

Through the Looking Glass: Adventures in Landgrant Land

2. Systems thinking and ecological perspective

A systems view of Western policy today

What systems thinking reveals: from biology to political

3. Capitalist social system

What Is the Deep State?

Forces Driving the US Political Economy

The Alchemy of Language in the Pacification of the American People

Locked In: The Paradox of Capitalism

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

A systems view of Western policy today

4. Energy depletion and cost accounting, and the future of industrial civilization

What is Sustainable?

Invisible Ships and Boiling Frogs: The End of Industrial Affluence

Humans Have Energetically Overpowered the Earth

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

Why Trying to Save Industrial Civilization with Alternatives to Fossil Fuels Only Makes Things Worse

Cities and Suburbs in the Energy Descent: Thinking in Scenarios

5. Agrarian futures

Human designs for ecosystem management and survival after the oil era

Food Production Systems in the Decline of the Industrial Age: A Call for a Socio-ecological Synthesis

Through the Looking Glass: Adventures in Landgrant Land

Implications for Agriculture of Peak Cheap Energy

Mass deception and the quest for a more sustainable agriculture

The Peasants Shall Inherit the Earth

Visioning County Food Production – Part One (of a six part series)

Topics: Memoires, Uncategorized | 4 Comments »

July 21st, 2020 at 10:44 pm

Wonderful reflection, Karl! (And thanks for the links in the Addendum!)

Earlier today we posted to Youtube yours and my “post-doom” conversation. Here’s the link: https://youtu.be/URQot1W5870

And here’s the project website: https://postdoom.com/

Keep up the great work!

For life and the future,

~ Michael

February 27th, 2021 at 10:10 am

Hi Karl,

I got to your site from a comment you made on peakprosperity.com. I’ve read several posts and got to this history. You’ve had a fascinating life.

I look forward to reading more of what’s here.

February 27th, 2021 at 11:42 am

Hi Richard,

Many of my articles address the same issues and concerns that motivate peakprosperity.com

August 26th, 2021 at 5:23 pm

Hi Carl,

We discuss much of this yesterday, however it was great to learn all you’ve shared here as well.

It is becoming more and more apparent that society is indeed bound by nature’s rules.

Respectfully,

Robin