« The prospect of a new Gothic Age in the US during the decline of the industrial era | Home | Wind and solar – societal and residential »

The Age of Modernity and its Discontents

By Karl North | January 27, 2019

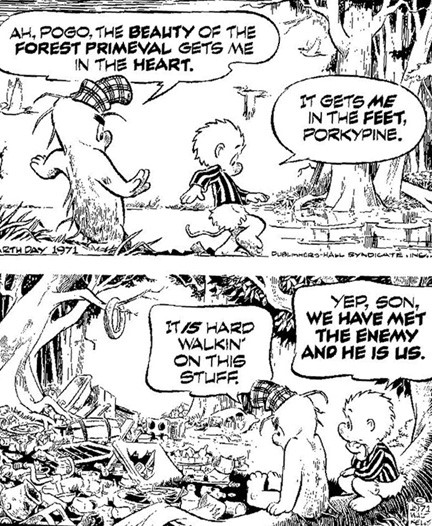

When the whole world is globalized [read modernized], you’re going to be able to set fire to the whole thing with a single match.

—Rene Girard

In human history, every cultural age is more than a collection of disparate elements. It is an interdependent, interactive whole some of whose elements need others to survive, as do species in an ecosystem. Some elements are ideas that justify others to us, forming an ideology. Living in the midst of an age like modernity, like fish unaware of the sea around them, we tend to take for granted many of its characteristics as permanent, whereas some are distinctive of this age and no other. Often, we focus on a few elements and fail to see how the cluster fits together as a whole.

Much has been written about the modern age (as in the early attempt by Freud, stolen for my title), but rarely from the viewpoint of its endgame due to the end of cheap energy and other raw materials[i]. In this essay I will look critically at modernity as a web of interconnections to offer a basis for exploring scenarios as to how it may come to an end.

The dominant narrative of the age of modernity describes it as the age of reason, science, mechanization, industrialization and urbanization, an age in which secular beliefs and values such as individualism, freedom and equality replace previous religions. A central belief is the quasi-religious faith in unlimited growth and progress using technology to control nature. Another is the belief that the rise of capitalism and democracy together represent the ultimate in social development, so that where they have been achieved, they constitute the end point of the development of human society, and “end of history” as it were. A dominant establishment-serving narrative depicts all these attainments as positive.

To deconstruct this narrative, I will consider prominent characteristics of the modern age separately, at the same time pointing out the interdependencies. A central focus will be on the two primary themes that characterize the modern age: the individualist/reductionist worldview and capitalism as a total way of life. I will show how their values fit hand-in-glove, reinforce each other to form an interlocking set of values and beliefs. That worldview has become the norm, one that we rarely question, and thus a kind of hologram in which we are imprisoned. The imprisonment offers a cozy faith that will influence the endgame of the modern age. Morris Berman, a prolific chronicler of America’s cultural decline, reminds us that according to Auden, “we would rather be ruined than changed”. The challenge, therefore, is to understand the modern age well enough to see what makes us cling to it.

A piecemeal way of making sense of the world

The world functions in wholes – complexes of interacting, interdependent parts. How those wholes work and how they might be altered by our attempts to navigate them are what we most need to know to manage our lives in them. Unfortunately, most of what we have come to call science in the modern age ignores those questions.

How did this happen? It occurred for several reasons. First, the complex systemic wholes that comprise our world are not amenable to the laboratory level of prediction scientists were seeking, where experiments are reliably reproducible. Hence, in the quest for predictive power the scientific community ignored the holistic nature of the world and reduced its focus to small pieces of those wholes: causal relations between two or three variables. How does iron react in the presence of oxygen, for example? Or, when a uranium atom is split, what happens to nearby atoms?

Also, this so-called reductive method divulged knowledge about immediate consequences of specific interactions that, when applied to managing our lives, yielded technologies of such power that they appeared miraculous by comparison to anything known in the past. From at least the 17th century the material impact of what might be called the Enlightenment Model on our lives was so great that constant technological advancement eventually replaced previously reigning monotheisms to become the secular religion of the age.

Steam engine worship

Moreover, because this way of advancing knowledge deliberately ignored inevitable, often negative ripple effects of technologies in larger wholes over time, it was extremely congenial to capitalism, a way of organizing society where competitive success depends on the ability to maximize short-run profit. Because they fit hand-in-glove, the two forces of the modern age, reductive science and capitalism, which reached take-off point together roughly in the 17th century, reinforced each other in a spiraling positive feedback loop. The results do much to define the modern age, its beliefs, values and the predicament that portends its downfall.

The worldview of reductionist science.

Evolutionary biologists tell us that for most of our species’ 150-thousand-year history, survival depended on acute awareness of immediate situations, a trait eventually embedded in our genetic faculties as the so-called fight-or-flight tendency. As our knowledge slowly increased of how things change over longer time spans and in larger wholes, our intuitive understanding of the connectedness of much of our environment increased, and encouraged more holistic worldviews, such as beliefs in a single, unifying creator. Unfortunately, when the Enlightenment Model of inquiry became the secular religion, it reversed past holistic trends, reinforced the genetically evolved tendency to see the world in small, immediate pieces, and created a kind of tunnel vision worldview that makes the modern age unlike any other. I say ‘unfortunately’ because this worldview has enabled humanity to expand, and so doing erode its own resource base to the point where it undermines industrial civilization and even threatens the survival of the species. If survival is a worthwhile goal, we must try to understand the modern worldview in all its impacts and fallouts in modern life, in order to counter it with a better thinking and navigating paradigm.

As the way we do science is a main source of the modern worldview, a first question is how it has shaped the advancement of knowledge. As the reductive method in different areas of inquiry expanded knowledge and required more skill, its development spawned specialization and compartmentalization in disciplines and isolated them from each other. A slow process, even as late as the 19th century great scientists like Darwin, Liebig and Marx assumed that their quest for understanding the way the world works required the mastery of numerous disciplines.

However, the result today is a knowledge culture characterized by specialization and a scientific community of idiot-savants: people savvy in their area of training but idiots in their inability to understand how a connected world works. Another result is that today we have fields of knowledge whose underlying assumptions sometimes contradict each other. For example, it is well known in the physical sciences how little importance in their calculations most economists, including Marxian political economists, allow to basic laws of energy and matter that apply to the use of natural resources for economic or any other purpose. Physical scientists on the other hand tend to belittle social and cultural causes and explain everything humans do exclusively in terms of genetic determinism or laws of matter and energy; and social scientists tend to disregard the effects of our genetic heritage and see humanity as a blank slate on which an almost unlimited variety of social and cultural forms can be built. The bounded rationality of the resulting disciplines – that their conclusions make sense as long as criticism remains within disciplinary boundaries – perpetuates their flaws.

Because research that was acceptable in the reductionist paradigm was incapable of accounting for the interconnected, systemic nature of the universe, technologies built exclusively on the products of reductionist science succeeded as predicted in the short run, but with more distance in time and space destructive consequences appeared and multiplied, exhibiting nonlinear behavior over time that the reductive method was not designed to capture or explain. Hence the modern age produced a long pattern of technological ‘miracles’ that are fundamentally flawed because derived from reductionist science. In the end the vaunted predictive power of purely reductionist science increasingly stood revealed as a short run affair, almost inevitably altered through time as the impacts of a single technological intervention ripple through the interconnected universe, generating multiple consequences.

A striking example of the tunnel vision is the unrestrained application of fertilizers born of the Haber–Bosch technology for the synthetic fixation of atmospheric nitrogen. Once celebrated for its narrowly conceived ability to vastly improve agricultural productivity, the unrestrained use of synthetic nitrogen is now revealed to have a constellation of negative ripple effects on agricultural systems: soil compaction, deadly destruction of soil food webs, adverse effects on plant health, diminished nutritional qualities of food, massive pollution of waterways and dependency on finite resources. Today it seems incredible that generations of agricultural scientists have promoted the practice, but the dominant reductionist paradigm conferred legitimacy on such narrowly researched technologies, and agribusiness capitalists loved how it could magnify their profits.

The dumbing down of problem solving as a cultural disease

The disproportionate focus on parts instead of wholes, and individual causes rather that systemic ones has spread from the scientific community to influence the way most people think of how the world works. It is worth exploring how different areas of life have been contaminated by this way of thinking.

In medicine. The dominant approach since the advent of the germ theory of disease has been to look for single causes. The increasing failure of this approach is giving way to a more holistic view – the systems perspective that causality arises from a structure of causally related variables, which makes better sense of the data, and is delivering more effective treatments. Evolution of thinking is forced, for example, by the growing category of so-called auto-immune diseases and others – cancer, HIV, lyme disease – that cannot be adequately understood in terms of a single invasive pathogen.

In law. The narrowly based culpability typical in Western law – where blame is often assumed to fall entirely on the individual – derives from a reductionist worldview that in this case ignores the social context of individual behavior. This is not to imply that individual culpability should be ignored, or that individual behavior that is a proven danger to society should not be controlled. But to ignore systemic causes, including the very structure of different social systems, is a distortion of causality and culpability. It is well documented in social science that different social structures give rise to different behavior patterns. We typically blame poverty, inequality, drug use, or school shootings, for example on individual failure – the ‘bad apple’ theory. But the pathological behavior of individuals cannot explain society-wide trends – in this case the rise of widespread undesirable patterns in modern society. For example, the guiding assumption of the US war on drugs put blame on the addicted, the drug economy or the producers, never on socio-economic system itself as cause.

In psychotherapy. Faced with the steady rise in mental illness over decades in modern society, scientists, reflecting their reductionist training, looked for biological causes in individuals although those could not possibly explain the trend in the whole society. This focus on the individual rather than society serves the interest of ruling strata in diverting criticism away from the social system itself. In the same way, the mainstream media serve capitalist interests in their reports of increasing shootings in schools and other public places by typically explaining them in terms of the psychopathology of the shooter, which fails to account for their emergence as a pattern in society that previously did not exist. Contextualization leads to identification of root causes in the larger system. As an example, family therapy succeeds by viewing deviant individual behavior as symptomatic of illness in the social environment – in the dynamics of family interaction.

In economics. The belief that behavior of the capitalist economy is entirely due to individuals pursuing their self-interest has gained wide acceptance despite the obvious effects of monopoly power and concentrated wealth, which are systemic in origin.

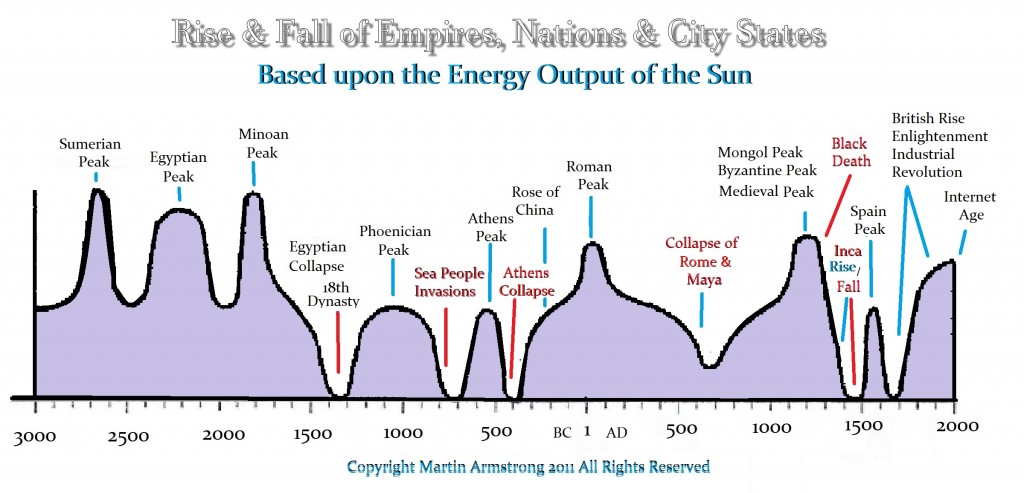

The cult of progress. Another belief in the modern worldview that derives from its scientific paradigm is endless growth. We believe that nothing can stop the ability of science to increase our knowledge of the world. In society, this manifests as a belief in a linear history of endless economic growth, technological progress and the perfectibility of society itself. In this belief the modern age is distinct from all past ages, in which change was seen as cyclic or at least encountered some limit. As will be seen when we discuss the erosion of the modern worldview, progress in science itself is revealing the shortcomings of the notion of endless growth.

The technosphere. The power and convenience of inventions born of scientific progress generate a cult of technology where material innovations shape decision-making in government, business, social and personal life – most of human existence in the modern age – in ways that override and suppress traditional values that are essential to quality of life. Technological progress in communication and transportation facilitates a distance economy where people at the consumer end of the supply chain cannot see, and therefore ignore, potential ecological and social harm caused farther up the line. Also, instead of the economy serving the people, people are moved around to serve the interests of those who control the economy. The resulting break-up of community and family, dispersing members over large distances, generates feelings of alienation and disenchantment, but is rationalized by the needs of a capitalist economy that gives priority to technological progress and the subsequent maximization of profit. The latest expression of the power of the technosphere is the smartphonization of human relations that replaces direct human contact with a device.

An age of cheap energy, the technosphere presents the individual with dozens of energy slaves who facilitate the cult of individual independence from society. The original ideal of the ‘rugged individual’ becomes a soft individual floating in a fairyland of appliances. The illusion of freedom from dependence on others encourages loss of empathy. The modern age is thus a harsh departure from millennia of traditional culture where the value of face-to-face human relations and local knowledge of geographical place prevailed. Freud was more right than he knew: civilization as we know it today breeds deep discontent.

Nature strikes back. The heart of the problem of backfiring technologies and in fact the end of the modern age is the habit of the reductive approach to knowledge to ignore and therefore violate basic laws of energy and matter, the so-called Laws of Thermodynamics. These are very settled science, not legislation that can be repealed by governments or anyone else. They state that stuff cannot be created or disappeared, but can be dissipated so that it’s no longer usable. Use it up, it’s gone, but only into a garbage dump or the air or water where it comes back to haunt us. Raw materials fashioned into man-made structures require constant inputs of energy to maintain them or they fall apart. Energy use can be recaptured for reuse but eventually escapes to outer space. When energy and raw materials are no longer cheap, the structures built with cheap energy will fall apart. So, the depletion of resources is not a problem with a solution, but a predicament, a situation to which we can only adapt. Hence a guiding conviction of the modern age – that Nature’s purpose is to serve us – is revealed to be Nature’s joke on us.

The capitalist element and its narrative

Previously I pointed to a convenient convergence of the ideologies of reductionist science and capitalism. I will try to explain elements of that convergence as I explore the influence of capitalism on the modern age and its worldview.

The term capitalism as used here refers to a total social system that includes not only a distinctive political economy that concentrates wealth and power via a positive feedback loop, but also distinctive institutions of government, media, knowledge acquisition and ultimately, indoctrinated cultural beliefs and values. It has been best described as an inverse totalitarianism, where a plutocratic class remains in the background and rules indirectly through major institutions. The plutocracy obscures this process by cloaking the institutions with an incessant mythical narrative that fosters the belief that the major institutions are serving the public interest. The result is a society in which the main decisions that shape our lives are in the hands of a private elite and give priority to its interests. A vast critical literature explains the workings of the capitalist system, so here I will focus mainly on its effects on life in the modern age.

Modernity as carte blanche. Starting at least as far back as the Western Renaissance in the 16th century, capitalism developed at an exponential rate to dominate worldwide in modern times. A key distinction of capitalism that makes the modern age different from previous ones is its ability to severely check attempts to apply rules of restraint in the quest to maximize capitalist profit. At least some previous social systems embodied a social contract that, however unfair or poorly enforced, limited the exploitation of labor. Feudal peasants had certain rights to natural resources, for example, and earlier societies imposed limits on debt peonage. As for management of the resources of the land, while social strictures were few – occasional sacred forests and mountains, for example – the low levels of technology and access to energy slowed the pace of abuse.

The lack of restraint under capitalism, promoted as ‘free enterprise’ and a number of other ‘freedoms’, had several consequences. First, it affected the use of human labor. A rare limit on labor exploitation occurred when starvation or poor living conditions weakened the labor supply enough to cut into profits. All the same, the unprecedented fortunes to be made in the industrial revolution led the investor class to sacrifice a generation of wage slaves to child labor and other afflictions. Thanks to the plunder of less industrialized nations, mature industrial societies enjoy a relatively high material standard of living, but most workers are still imprisoned in an alienating rat race of economic insecurity and unfulfilling lives palliated with induced consumerism. In some industrialized nations organized labor and the threat of revolt has curbed exploitation somewhat, bringing about a so-called welfare state. Even in these countries, the welfare state is fading as US hegemony since World War II has imposed an extreme model of capitalism world-wide.

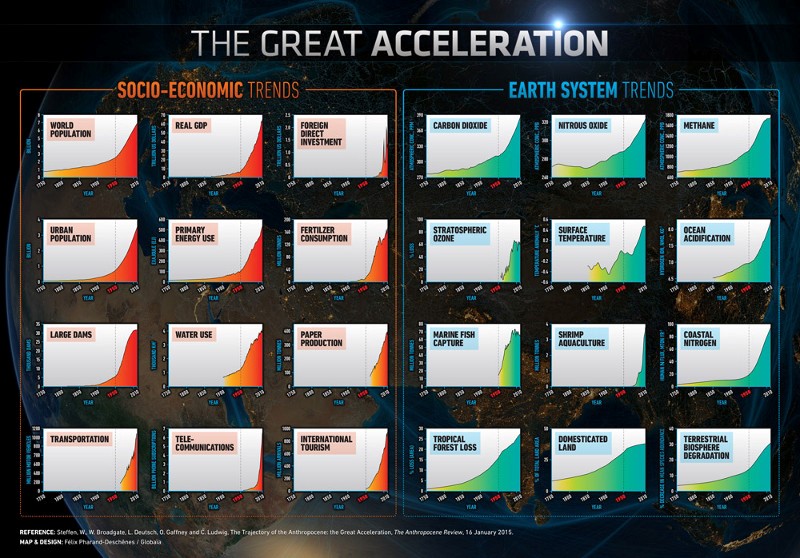

Second, powered by concentrated fossil energy, extraction of raw materials including top soil and water has grown exponentially, constrained only by what an economy can use at a given time. The irony is that depletion and other damage to the resource base has reached a tipping point where it undermines the industrial civilization that defines the modern age. The capitalist system appears unable to reverse the exploitation, so catabolic collapse seems inevitable, bringing modernity to an end.

A third liberalization in capitalism that sets the modern age off from previous ones is a highly evolved form of what used to be called usury, as part of a general evolution of capitalism through stages of evolution that are more or less predictable from its structure. Just as ecosystems develop more complexity over time in roughly predictable phases called succession, capitalism evolves more sophisticated forms, such as imperial expansion, the increase of monopoly power and the so-called financialization of the economy where an ever-larger financial class increasingly usurps control over investment from the industrial elites. In the present stage of financialization, usury – the renting of capital at interest to acquire unearned income – instead of investment to produce real wealth, takes on increasingly risky speculative forms such as junk bonds, derivatives, currency speculation and unpayable mortgage loans. The outcome of unfettered usury increases debt peonage at all levels – individual, corporate and government – to the point where an economy can no longer function.

Ancient civilizations learned that unrestrained credit eventually imprisons a society in debt peonage, and devised checks such as write-off events that erased debt, and laws that imposed limits on lending, culminating in a total ban on usury by the medieval Christian church. Anthropologist David Graeber and political economist Michael Hudson have chronicled the fascinating 5000 year history of debt and the development of constraints on usury, and underlined their importance for global society today, which is in a late stage of debt peonage imposed by a powerful transnational financial class. Global debt is at an all-time high of $184,000,000,000,000.

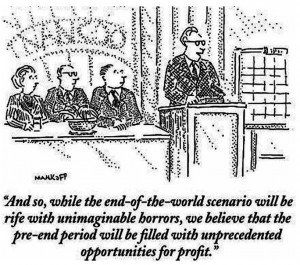

Capitalist economies run on interest-bearing debt. In periods of economic health, growth normally produces a surplus sufficient to cover interest costs. Now as permanently rising resource scarcity slows growth, economies are increasing debt-based investment to artificially sustain growth. But in consequence, rising interest costs are dragging economies down in a vicious circle. Always prone to bouts of economic depression due to over production, major capitalist economies now face deeper crashes as they struggle under current debt levels. This is the economic end game of the modern age. The end game does not threaten the capitalist class because it can adjust to take advantage of investment opportunities opened by the chaotic aspects of industrial shrinkage.

The Waste Makers. Paradoxically, one of the fortunate products of capitalism is wastefulness. Capitalists discovered that the best way to maximize short term profit is to turn raw materials into garbage as fast as possible. Cheap energy convergent with sophisticated forms of mind control in the 20th century spawned enormous waste, from planned obsolescence to products that are useful conveniences but not necessary to live the good life – everything from microwave ovens to airplanes. Cheap oil also allowed the luxury of inefficiencies in production and consumption. At the end of the modern age, much of the production of waste and inefficiency might be properly viewed as a godsend: slack or wiggle room because nations could theoretically stop the waste and invest the otherwise wasted resources in adapting industrial society to its demise. Whether they will or not is another question.

Ideological hegemony. To maintain peace, a social system that allows a rich minority relatively unlimited freedom to exploit the majority must have an effective ideology of pacification. Under ruling class control, common sources of information – formal schooling, mass media, government public relations –are used to colonize and imprison the collective consciousness with an establishment narrative of reality that serves a steady diet of simplistic propaganda. Capitalist ideology benefits in several respects from the way reductionist science reduces inquiry to the smallest parts because it promotes the primacy of individual rights over communal ones.

First, the establishment narrative succeeded in disguising its control of major institutions behind a mythology of individual freedoms: free enterprise, free press, free trade, academic freedom and freedom to consume in a free market. The ideology of individualism also worked to diminish a sense of collective responsibility, and instead encouraged fundamentalist credos like born again Christianity in the commoners and extreme post-modernist relativism in the educated classes. The “Land of the Free” illusion has been highly successful. As John Steinbeck allegedly remarked, the working class sees itself not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

Secondly, the accentuation on the individual helped divert critical attention away from how the system works as a whole. It marginalized dialectical macro-systems model builders like the Limits to Growth authors, William Ophuls, Lewis Mumford, Morris Berman, Michael Hudson, Noam Chomsky and a long list of Marxian social scientists, whose analysis of the existing system and its patterns of change has exposed the illusions of the indoctrinated conventional wisdom. In addition, much of the scientific community denigrated these efforts and indeed all of the behavioral sciences as ‘soft science’, as not amenable to prediction. The joke is on the reductionists, for as we shall see in my concluding section, a revolution in how science is done is demonstrating ability to gain some understanding of the complexities of the real world, which the reductive method has never been able to achieve.

Thirdly, the ideology promotes a collapsed sense of history, particularly in the US – a kind of organized forgetting: history is what happened last week. Instead of teaching the importance of seeing present as history, that is, as the culmination of significant historical patterns, it encourages disinterest in history, replacing it with a cultural apparatus that focuses attention on the exciting present where kitsch and the next novelty in the marketplace replaces attention to fundamental issues like class and power. Consumerism becomes the dominant value and is normalized: if you don’t shop you aren’t a good contributor to the society. Comparisons with Europe where the public still has some sense of historical context have called the US ‘the Republic of Amnesia’.

Finally, the storyline paints the modern age as the pinnacle of perfection – “the end of history”, in the words of one academic ideological zealot. The accession of the major competing social systems, China and the Soviet Union, to capitalist penetration gave ideologues the opportunity to reinforce belief that modern Western capitalism is the most advanced form of civilization possible. “There is no alternative”, announced Margaret Thatcher.

The modern age as cityscape

Civilization, a way of life characterized by the growth of cities, matured over 5000 years to become the dominant way of life in the modern age. Urban populations as high as 80% in many countries epitomize late stage modernity. Cities are urban concentrations of wealth and population large enough to require the importation of resources by exploitation of peripheries. Thus the city is empire on a small scale. Its mode of exploitation requires violence. Geographer Christophe Guilluy, explains the result today:

Employment and wealth have become more and more concentrated in the big cities. The deindustrialised regions, rural areas, small and medium-size towns are less and less dynamic. But it is in these places – in “peripheral France” (one could also talk of peripheral America or peripheral Britain) – that many working-class people live. Thus, for the first time, “workers” no longer live in areas where employment is created, giving rise to a social and cultural shock. … The globalized metropolises are the new citadels of the 21st century – rich and unequal, where even the former lower-middle class no longer has a place. Instead, large global cities work on a dual dynamic: gentrification and immigration. This is the paradox: the open society results in a world increasingly closed to the majority of working people.

Guilluy sees the rising ‘populist’ revolts in industrial economies, such as the 2018-19 Gilet Jaune uprising in France, as an inevitable consequence of this latest stage of urbanization.

Now globalized and nearing the end of its resource frontier, the highly centralized system of late-stage modernity into urban clusters is increasingly fragile according to systems-thinking risk analyst Nassim Taleb. Electronic communication and cheap transportation along with urban concentration have facilitated the growth of a global economy whose precariously long supply chains and dependence on far-reaching webs of electric grid and financial homogeneity make it highly sensitive to disorders like trade wars and resource wars. Compounded with the incessant undertow of a gradual end to cheap energy, it is a system that is vulnerable to deep shocks, even collapse.

Crumbling modernity and revolutionary potential

The modern age spans five centuries in which the behavior of modern society evolves under the combined influence of key themes that I have tried to describe. The age of modernity will come to an end due to exhaustion of its unique energy supply and resource base. This will come as a shock to most people because we have been led to believe that modernity is permanent. We will begin to understand the modern age as a discrete era with a beginning and ending, as we have understood previous ages such as the bronze age, the age of city-states, the age of monotheisms or the many empires since the advent of agriculture, the lifetime of each one delineated by its period of rise and fall. Maybe this will put the age of modernity into a different, more detached perspective and help us navigate its decline.

The end game of modernity is characterized by an accumulation of discontents, widening cracks in the dominant scientific paradigm and cannibalization of its resource base. Social commentary films like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, coming near the end of the age, capture a number of social patterns that express the accumulation of discontents. This film displays a disparate but somehow connected web: two top corporations, one immersed in global crime networks and the other infested with a virulent fascist ideology; cases of pathological family disfunction in both top and bottom social strata including a serial killer, child abusers and violence against women; the influence of digital media on individual identity; investigative cowardice and incompetence in journalism and criminal bureaucratic indifference in social services in a supposedly ‘welfare state’. An abiding issue in both the film and the wildly popular book on which the film is based is the degree of complicity of social institutions in the crimes of individuals.

To confront the accumulation of discontents engendered in the modern age by the Enlightenment Model, a gentler, a humbler approach to the advancement of knowledge is needed than provided by that model. As it happens, as early as the 1960s Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions opened the door to that possibility by proposing that the advancement of knowledge proceeds as one scientific paradigm or way of doing science, plagued by accumulating anomalies it cannot address, yields to another. As Kuhn defined it, a scientific paradigm is a shared vocabulary, a shared methodology, and a shared view of what matters. The results of the reductive method have revealed limited application outside the laboratory. So “what matters” extends beyond prediction under controlled conditions to how things change in the messy, systemic connectedness of real life. Hence, a revolutionary paradigm shift is occurring, at least in certain fields of study, as we develop methods of understanding the complexity that typifies how the real-world works, which the Enlightenment Model was never designed to do.

In an earlier example I described the limits of the reductive paradigm in the effects of synthetic nitrogen on agroecosystems. Here is an example from social systems. The conventional view of the global situation sees the world through a narrow reductionist lens: the elements of the crisis – the contradictions of late stage capitalism, the many types of ecological damage to the planetary resource base, global resource depletion, the rise of the authoritarian state and the decline of the US geopolitical hegemony – as isolated problems. This makes them appear more manageable than they really are; seeing their interdependence reveals that their mutual interaction and influence amplifies the crisis.

The complexity science revolution is driven and shaped by breakthroughs in epistemology (how we know) that accumulated in the modern age:

- Awareness of the recursive nature of investigation – scientists are part of the systems they observe.

- Awareness that objectivity is impossible: our understanding of the world is limited by indirect contact through our senses, and by the interpretations our brain makes.

- Awareness that its whole way of inquiry is shaped by the cultural worldview of the universe scientists live in. (Kuhn)

- Acknowledgement that Newtonian certainties and determinism are tempered by being embedded in a much larger world of complexity where inquiry can yield only propensities, probabilities, and uncertainty.

- Discovery of the limits of rational inquiry in the advancement of knowledge. The thinking of the modern age is, in the words of one systems scientist, “trapped in the Enlightenment Model, which posits that human choices are determined by reason and factual information (and if not yet, then should be)”.

- Awareness of the need to expand the context of scientific inquiry to encompass larger relevant wholes.

- Acknowledgement that most behavior that arises from complexity is nonlinear over time. To gain insights that help explain the shape of this nonlinear behavior, a science of complexity must model systemic structures of positive and negative feedback that achieve temporary, shifting balance.

- Acceptance that ecosystems science encompasses all living systems and their inanimate elements, including social systems, and is therefore the master discipline that is providing a new framework to underpin all scientific inquiry.

Some of us are old enough to have been participants in a period of intense questioning of all sorts of conventional wisdom known as the Sixties Counterculture. The current revolutionary shift to a new scientific paradigm is part of a similar ferment that one participant has dubbed the Systems Counterculture.

A timely example of the new paradigm of inquiry might be to ask how we should study the next decades of global human existence as the modern age ends. Because we are dealing with a complex problem, claims to prediction are often impossible and reveal ignorance of the nature of complexity. We can sometimes predict what will happen if such change is driven by well-tested principles like the Laws of Thermodynamics. But in complex systems, when and how things will change is not predictable. The best we can hope for is to explore different scenarios and try to estimate their levels of probability. Barring early human extinction events like nuclear armageddon, runaway climate change or planetary pandemics, multiple scenarios are possible. Declining energy will limit possible scenarios as carrying capacity erodes to support only much lower human population levels.

[i] See Invisible Ships and Boiling Frogs: The End of Industrial Affluence, Humans Have Energetically Overpowered the Earth and The Industrial Economy is Ending Forever: an Energy Explanation for Agriculturists and Everyone

[i] Morris Berman books and reviews.

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Systems Thinking Tools, Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

March 30th, 2019 at 4:04 pm

I take Wendell Berry seriously, especially The Unsettling of America and Life is a Miracle