« Mass deception and the quest for a more sustainable agriculture | Home | An ecology of social systems »

The Peasants Shall Inherit the Earth

By Karl North | August 30, 2018

It is said that prediction is difficult, especially about the future. Nonetheless, a few Romans saw the inevitable fall of the Roman Empire more than a hundred years before it completely disappeared. Their prediction was possible because they saw that the system was depleting resources essential to its survival, so had trapped itself into a cannibalistic situation where it was gradually cutting its own throat. No policy to voluntarily reduce consumption to within carrying capacity was politically viable, because that would end the empire as well. And neither the patricians or the plebs wanted that!

Again today the world is in a similar situation: the end of the industrial era is predictable because the end of cheap fossil energy and other cheap raw materials that currently sustain it is in sight, at least to a few. I have summarized this situation from different angles elsewhere[1], and it forms the premise of what follows.

Eric Wolf’s pioneering anthropology of the peasantry begins with the observation that “they are important historically, because industrial society is built on the ruins of peasant society”[2]. And yet today populations who are still in some sense peasants are still the global majority, however besieged and compromised by the global industrial economy. The thesis I will present here is that the peasant way of life offers the best opportunity to survive the demise of the petroleum era. I will describe peasant traditions in various areas of life – farming and other uses of the natural resource base, redistributive social structures and relatively communal political arrangements – a heritage still existent or retrievable that makes peasant society most likely to weather the constraints of a declining industrial civilization.

Resilient ecosystem management

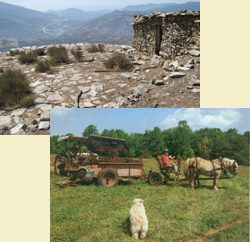

As the energy descent deepens, it will raise costs and send into decline all energy intensive activities. These include not only industry but industrial agriculture and forestry on which society relies for its most basic needs: food and shelter. The best of historical peasant systems to serve these needs at low energy cost have mirrored the resilience of natural ecosystems in their diversity of species use, their small scale serving a local economy and above all in their reliance on input self-sufficiency – reliance on inputs like seed, fertility, and power that are found or created within the system, not synthesized using fossil energy. Some examples are the Aztec wetland chinampa gardens[3], agrarian communities based on the floodable great meadow in lowland Europe that spread to early colonial New England[4], the azolla/duck/rice[5] and other paddy systems in Pacific Rim countries[6] and traditional Mayan milpa agriculture. A general model of this ideal type and some examples are described in my Visioning County Food Production – Part Two.

Resilient Social Organization

Two conditions provide the bedrock of peasant resilience: control of at least some of the surplus above subsistence needs that became available with the advent of agriculture, and relatively permanent rights, however limited, in the land that creates the surplus. They usually retained these rights despite the growth of parasitical higher powers like feudal aristocracies who expropriate some of the agricultural surplus. Inheritance rights maintained the resilience over time.

Peasant communities everywhere typically created rules to conserve some of the surplus as stocks of grain or other conservable staples or livestock as a savings bank for redistribution to the community in times of need. They created ceremonials and rituals that sustained belief in these rules, first at the level of the nuclear family, then the extended kin group, and then the village.

[1] Humans Have Energetically Overpowered the Earth, Locked In: The Paradox of Capitalism,

The Future of Industrial Society: “Progress”, A Microscopic Scientific Paradigm, and Blowback

[2] Wolf, Eric, Peasants, 1966.

[3] http://www.chinampas.info/, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinampa

[4] Donahue, Brian. 2004. The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord.

[5] Furuno, Takao. The Power of Duck. Tasmania: Takari Publications, 2001

[6] King, F. H.(Franklin Hiram), Book Farmers of forty centuries; or, Permanent agriculture in China, Korea and Japan.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments »