« How the Maximum Power Principle affects living systems | Home | The Pace of Descent: A Long Emergency vs. Sudden Collapse »

What is Sustainable?

By Karl North | January 8, 2018

Answers to this question that are rooted in the relevant scientific disciplines – primarily systems ecology, the physics and economics of natural resource science and the world-system method of the history of civilizations – are so unsettling to most people in their implications for the future of modern civilization that they are met with denial. Systems ecology reveals that all systems that overshoot their carrying capacity in natural resource use eventually collapse. Natural resource science tells us that consumption of finite sources of energy and other raw materials depletes them in a standard pattern – an asymmetric bell curve whose downside is steeper.

The history of civilizations as world systems discloses that all civilizations prior to ours have collapsed. Or they have given way to invaders with better technology and new resource frontiers. At present there are no more resource frontiers. In that respect the planet is fully occupied. The combined implications of these revelations for our civilization are unthinkable for most people.

What to do? Perhaps what is needed is a way into the problem that is gradual and indirect enough to avoid provoking denial, and an initial target group that is more approachable than the general public. All notions of sustainability of human society depend on how necessities of life – food and shelter – are produced. Hence farmers and agricultural scientists have begun to use the term in many ways in recent decades, as have environmentalists (although unfortunately with little knowledge of the above mentioned relevant scientific disciplines). Consequently, these groups at least acknowledge the importance of the concept. A recent book that tackles the problem head on, but in a way that might gain access to the environmental and alternative agriculture movements is What is Sustainable: Remembering Our Way Home by Richard Adrian Reese. What follows is a short review of the book.

Reese is the typical urban expatriate who finally got fed up with his career and lifestyle in a midlife crisis and bought an abandoned farm. Having no rural or farming skills, he embarked on a crash course to learn these, but also to read a huge booklist of the literature in any area of inquiry that might be relevant to the question of what is sustainable. If nothing else, his book is a comprehensive review and introduction to this literature.

His booklist does not include the relevant scientific texts themselves; rather it covers the secondary literature, often written by scientists whose aim is to bring to a general public the perspective of their discipline on the subject. Typical of the wide range of literature that Reese draws on are titles like Changes in the Land, a detailed account of how European land management displaced more sustainable indigenous land management in colonial New England; Topsoil and Civilization, a history of the rise of civilization and its damage to soil; The Myth of the Machine, an analysis of the central tenet of the industrial worldview; Tree Crops – A Permanent Agriculture, a valuable compendium on agroforestry; Collapse, an inquiry into the rise and fall of a number of civilizations; and The Long Descent, one of the best examples of the energy descent literature.

Reese has a knack for extracting the core messages from this literature in pithy remarks that drive home important conclusions. His summary of the literature and its conclusions is thorough enough that it covered all of the important works that I have absorbed in a half century of study and teaching of the subject, and then some. Reese’s conclusions challenge the idea that anything like modern civilization and its agriculture, including most currently practiced agricultural alternatives, can last much longer. However, his method – following his own gradual learning trajectory – presents the argument repeatedly from many different angles, and may be palatable where more direct arguments from science so far have failed. Among the perspectives he shares to make his case are:

- An evaluation of many pre-agricultural economies based on their anthropology

- An evaluation of many agricultural economies in their 5-millennium history to the present

- A critical history of technology and its consequences

- The question of population, its history, taboos, regulation and its bubbles that popped

- Worldviews, functional and dysfunctional, their embedded perceived necessities and other traps

- Modern lifestyles vs our paleolithic genetics

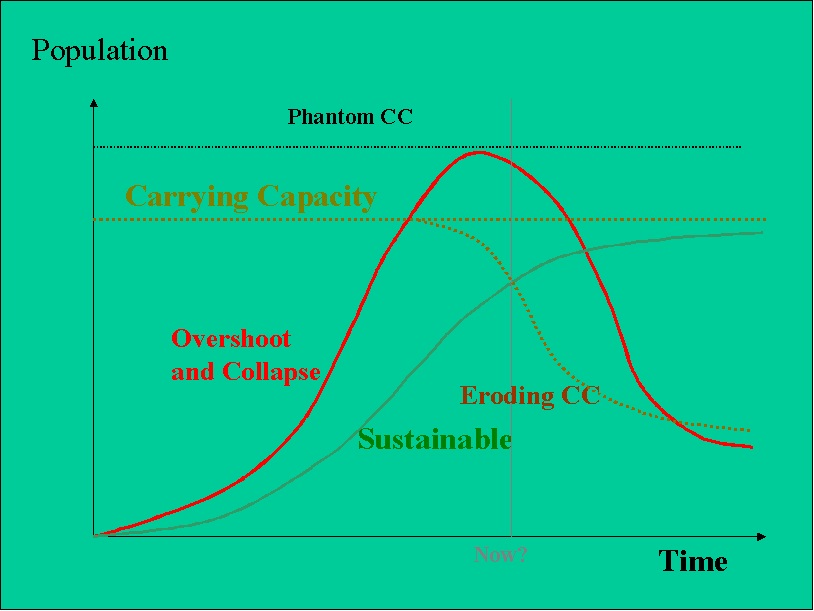

Although understandable in the approach of a layman on a steep learning curve, Reese’s book exhibits little evidence of knowledge of the sciences that I said are relevant to an understanding of what is sustainable. The works he relies on are often written by scientists in the relevant fields, but present mostly interpretations of historical data, not the powerful concepts that scientists use to order the data. Thus, the lack of clinching arguments based on modern systems ecology are a limitation of the book. Theoretical considerations essential to thinking about sustainability must include the relationship of carrying capacity and its erosion, phantom carrying capacity (a term coined by systems eco-sociologist William Catton), and overshoot, as demonstrated in this time graph,

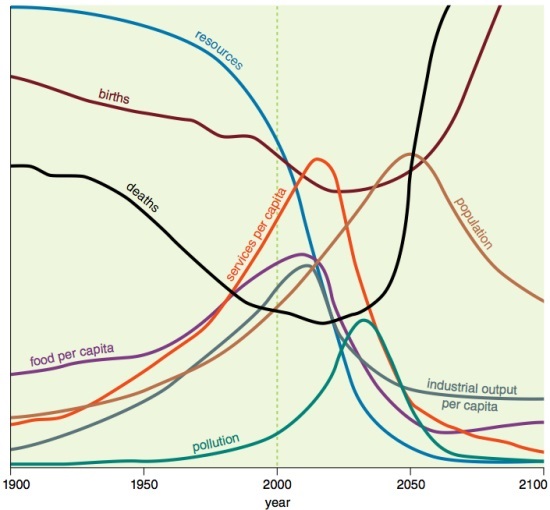

and its devastating use by the Limits to Growth project to demolish the myth of everlasting growth and material progress, as in this scenario.

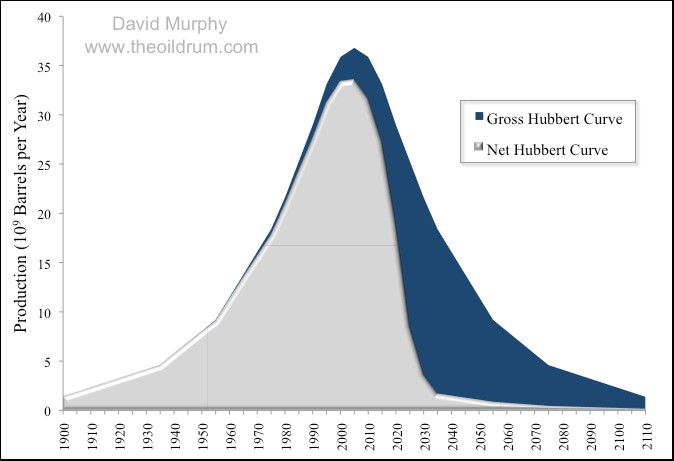

Reese also could have made more use of the so-called peak oil literature that appears in his bibliography, which focuses on the depletion of cheap fossil energy, the all-important understanding of declining net energy, the extravagant energy costs of industrial economies and their consequences and implications.

Another limitation of the book is Reese’s lack of any of the penetrating tools of inquiry known to political economists. Despite numerous superficial remarks regarding exploitation and its victims, Reese never manifests an understanding of the power structure of our society, the power elite that is orchestrating much of the predicament he writes about, and how it all works. Hence all the bad things just “happen”, or he eventually blames the bad fairies, and hopes that the good ones will prevail. A grasp of the structure of class and power in capitalist societies is essential to see why the collapse of industrial civilization is happening the way it is, and to explore probable scenarios of how it will play out.

Still, I would recommend the book as a user-friendly, lay approach to learning or teaching the question of what is sustainable. Reese has brought together in a single work important lessons from a voluminous literature.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Recent Additions, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Sustainability Assessment Tools, Uncategorized | 5 Comments »

January 8th, 2018 at 4:42 pm

Karl, I agree with your appreciative critique and suspect Rick Reese would, too.

See, for example…

His recent post, “Sustainability Primer”

http://wildancestors.blogspot.com/2017/08/sustainability-primer.html

His review of Catton’s “Overshoot”: http://wildancestors.blogspot.com/2014/10/overshoot.html

His review of “Limits to Growth”: http://wildancestors.blogspot.com/2015/03/limits-to-growth.html

January 10th, 2018 at 12:50 pm

I have now added an important paragraph at the end that I neglected to include in the original, and made some other minor edits.

January 11th, 2018 at 7:49 am

Excellent addition.

~ M

January 12th, 2018 at 1:09 pm

Your overshoot graph is the best I’ve seen. I used it in an evening presentation I delivered last month.

Did you create it or is there someone else I should credit?

January 12th, 2018 at 2:58 pm

My creation using Catton’s work.