« The Orange Revolution Comes Home to Roost? | Home | A holistic view of catabolic collapse »

The quality of peasant life: a scenario for survival

By Karl North | November 17, 2020

Histories of peasant life that characterize it as nasty, brutish and short ignore the vast variety around the world of peasant quality of life and attendant differences in environment, social organization and culture. Differences of degree of overlordship alone range from several layers of overlords to complete autonomy. It is just this great variety, the fruit of adaptation to site-specific conditions, that offers peasant communities that retain elements of subsistence agriculture the chance to survive the demise of industrial civilization. For those who do not turn up their nose at learning a little social science, let me offer a synopsis of one case as an example: the Albigensian or Cathar heresy that emerged in late medieval southern France.

Conventional history of the phenomenon focuses almost exclusively on the religious doctrinal differences and the northern crusade that eventually crushed the renegade movement. However, as any anthropologist knows, religious divisions are often a signal for underlying differences of a cultural nature. In the late Middle Age, society in the south of France retained much of the richness and sophistication of the Roman Empire, whose eclectic mix of cultural beliefs from around the Mediterranean and beyond never penetrated deeply into the north. Thus, southern France was a natural breeding ground of deviance from the stark doctrines of the Church. It was not a coincidence that the core of the Albigensian movement was in Toulouse, on an old trade route between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and close to the foothills and mountains of the Pyrenees. Mountain people have often been hard to govern, and the Pyrenees provided both a breeding ground of heretics and a safe retreat as the crusade heated up. As we shall see, the difficulties of terrain, the distance from centers of power, and the inviting presence of the Spanish border allowed the peasantry in mountain villages to gain considerable autonomy.

The French peasantry experienced three layers of formal overlordship – King, Church and nobility. But in the 12th and 13th centuries the royalty and nobility, which the Church relied on to carry out its crusade against the renegades, were not as strong as they became later. Moreover, many of the southern nobility were “infected” with the heresy, and first had to be brought back “to the fold” to be of any use in the crusade. The aristocracy often had trouble even extracting its tribute from villages located in its mountain lands; so stamping out the heretics in those places was often the least of their problems of governance.

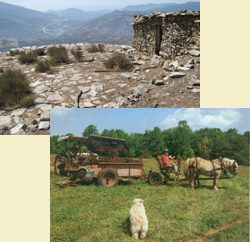

In the Pyrenees, agrarian peasant villagers practiced mixed horticulture centered on livestock. As in many pastoral systems, the herd/flock is the savings bank; it is the source of wealth for trade and is included in the census of the population for taxation purposes. Villagers employed herders who managed flocks of many families and ranged far and wide, even across the border into Spain, moving flocks to higher altitude and back in the seasonal migration cycle – the transhumance. Villagers had relationships with traders and others in market towns in the lowlands on both sides of the border. Nobles rarely went up into the mountains, but governed indirectly through village headmen. So it was easy to hide flocks to avoid the tax count, and to trade on which side of the border best escaped the tax man. Relations in market towns would provide cover for trade deals that might be too revealing of wealth.

In the mountains, the ministry was often provided by circuit rider priests. Preachers of the heresy were often informal or defrocked priests who could hide in extended families, convert a whole village, and as the heresy hot spot became known to the authorities, escape to another village on the circuit, or cross the border if necessary.

These brief remarks that evidence considerable religious and political-economic autonomy barely graze the surface of the various freedoms from overlordship and the resultant quality of life that the mountain peasantry enjoyed. The primary source for further education on these matters is Montaillou: The world-famous portrait of life in a medieval millage by anthropologist Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie. It is actually a portrait of the mountain peasantry and its lowland political, economic and religious relations in the whole region. Montaillou was the last village that actively supported the heresy, becoming the center of a revival nearly a century after the Church and its minions had crushed it elsewhere in France. This anthropologic work reveals that behind the religious autonomy a mountain peasantry had created a niche of more general self-sufficiency and self-rule that was political, economic and cultural, which protected it to a surprising degree from external forces of all kinds.

These two historical examples, from the Pyrenees and Bali, offer food for thought on the question of what forms of social organization and ecological integration will ensure the survival of the peasantry of the future.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Sustainability Assessment Tools, Uncategorized | No Comments »