« A holistic view of catabolic collapse | Home | Polarization in crisis: Nazi Germany and US today »

Farm restoration – a Downeast Maine story

By Karl North | February 9, 2021

More a set of recalled vignettes than a systemic history, this essay will at least capture some of my photo archive in an explanatory framework.

Property purchase and rebuilding

As we drove up to the top of Ridge Rd. in Robbinston to the last visit on our hunt for a retirement farm in Maine, the vista that emerged of the New Brunswick hills across the St. Croix estuary two miles away got mentally fixed as a major determinant of our decision to relocate on the property we were about to see. A second determinant was that it included most of the built capital of a small working farm – farmhouse and outbuildings, hayfields, fenced pasture and haying equipment. This property would allow us to continue homesteading and even farming at a retirement level, as we had done commercially in New York state. A third determinant was to bring parts of the family together. My daughter’s family, who had moved to Maine from California, expressed a desire to find a place where we could all live. They agreed on the Robbinston property and we gave them a stake in it. But eventually they found the employment prospects here too daunting, and remained in southern Maine, closer to work in Boston.

At first glance the place looked to be in reasonably good shape. Only gradually did it emerge as a major fixer-upper. The current owners had bought an abandoned, worn out farm. Apparently they could not afford permanent restoration of the land and buildings, so they had settled for cosmetics and half solutions.

As a farmer of thirty plus years, my first instinct was to check out the main barn.

On entry it revealed an attractive structure in the old wooden-pegged post and beam style, a main bay rising to the roof and side bays with pens (one currently occupied by a small goat herd and a small milk cow and calf) and overhead hay lofts. The roofing asphalt appeared to be relatively recent. The manure and bedding had been building for years, which I saw as a major asset. All the places I have farmed started with worn out soils. On my previous farm in New York I had jump-started soil regeneration with bedding packs cleaned out of neighbors’ barns and free for the digging. Here was another such opportunity that came with the farm.

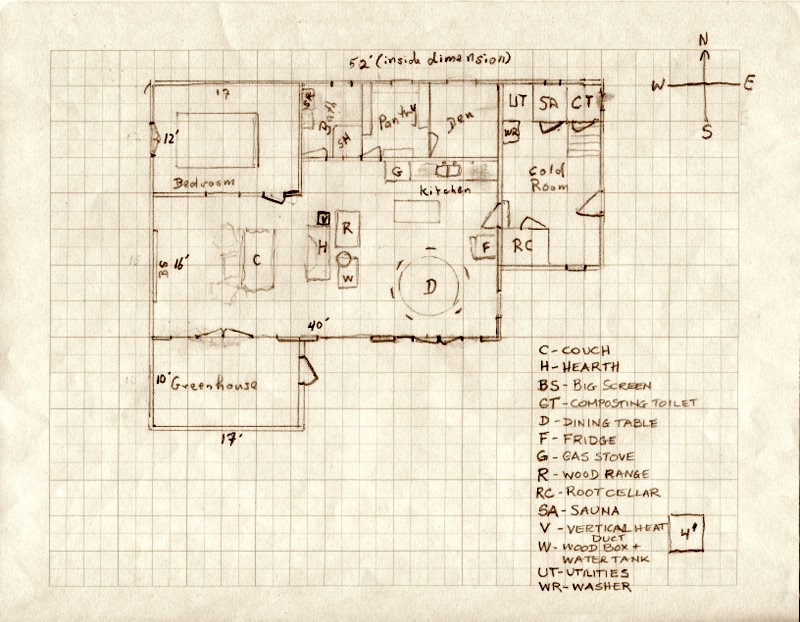

Closer inspection exposed so much deterioration in the barn that restoration would be a constant money sink. The recent reroofing hid rafters that were dangerously rotten, as my son-in law Wil discovered when he volunteered to dismantle the structure. The siding was so dilapidated that it had been covered with cheap tarps on the east and south sides (another half measure) to protect the barn interior from the formidable blasts of occasional nor’easters that come off the bay and hit this hilltop. The barn also occupied the best location for the house I had in mind for our move to Maine – a third opportunity to improve my amateur attempts at passive solar design. And the one story, open-sided pole barns I had built to create the previous farm in New York were far more convenient to work in. So, the barn was slated for demolition, a project that reportedly angered the previous owner, but luckily only discovered after the she had sold the property to us and moved to Michigan.

The current owners had given the old farmhouse a facelift of cheap vinyl siding and windows and a little insulation under the roof. But like most old farmhouses, it still devoured many cord of firewood, as I discovered camping in it while overseeing the construction of the new house on the property. But the roof leaked only around the chimneys and porch, so we decided to use it for storage and lodging any hardy visitors (to date there have been no hardy visitors).

We were able to pay cash for the place (bankers are usurious parasites) in early Spring 2011, and immediately conducted interviews with prospective builders. None were familiar with passive solar design but I found one who was enthusiastic to work from my drawings and homegrown blue prints. A friendly architect in Ithaca had given me a one-day crash course in drafting, but it turned out that the builder was better at working from the drawings than my laborious efforts to create blueprints to scale, despite their professional quality.

Barn demolition took longer than expected, Construction on the new house began in June with earth and foundation work by local people who were expert at their professions. To keep the carpenter crew happy until the foundation was ready for carpentry on July 4th, I set them to building two pole barn sheds one for vehicles and equipment and the other for sheep.

As luck would have it, the builder had rounded up a construction crew each one of which had all the skills to be at ease with the elements of my passive solar design, which I described in detail in the last section of Three Farmhouses: A Study in Passive Solar Design. The team actually made some improvements and revisions for which I was grateful, changing the placement of the bedroom door, or crafting a attractive style for the insulating shutters, for example.

My initial relationship with the carpenter crew I would describe as standoffish polite, as locals tend to be with people from “away”. As team leader, the builder’s role was to handle all interaction with me. The crew did most of the work and deemed themselves superior in skills to the leader, but tolerated him as leader because he took on all the uninteresting clerical work: billing me, paying them, working with the other contractees and ordering a timely stream of construction materials. So, I rarely had a reason to interact directly with the crew. As general contractor I became somewhat acquainted with a number of contractees, but rarely with their crews. However, as architect of the rather unique house the crew was constructing, I had gained a bit of grudging status with the carpenters. I decided to improve on that by taking on two jobs: painting the cedar clapboards and other siding, and vacuuming up the mounds of sawdust after each day’s work on the interior. These were menial tasks beneath the responsibility of the crew, so they were happy to see me take them on.

Conflicts on timing arose occasionally between the builder, the earth mover, the chimney mason and the specialist who I contracted to apply an unusual stain finish on the concrete floor. I learned about such glitches when the parties grumbled to me privately. But since they were all locals who knew each other, often from childhood, I figured that they would work things out.

As the fall season arrived, I tested out the new fireplace, a so-called Rumford design based on the old colonial heating hearth, and relatively energy-efficient for an open hearth, then retreated to NY for our last winter in the state. By then I was sufficiently impressed with the building crew to let them finish the interior without oversight. The new house would have no heat but the sun until we moved up the trusty old cast iron kitchen range that had done superb duty for thirty years in the NY farmhouse. The builder, unaccustomed to the heat storage capability of energy efficient design, feared freezing pipes, and moved in a gas heater for the winter. To his amazement, he never had to turn it on, for the house temperature rarely dropped below 60°F.

The carpenters put the finishing touches on the interior by early winter. Photos the builder sent back to us in NY revealed a visually attractive interior with the warm feeling that I had hoped for from ample use of the inexpensive timber resources that dominate the landscapes of the state. We declared the house a success. We had invested our bits of inheritance and savings over the years in more lucrative places than our farming ever yielded. Occasionally these placements did well. We often say that this is the house that Netflix built.

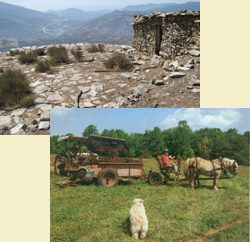

Once installed permanently on the new property in June 2012, and a garden and a brick patio started, we took time to enjoy the view of the water. We also began to encounter the uneven legacy that the previous occupants had left on the property and in relations with the neighbors. New to the vocation of farming, the last occupants had struggled for several years with a steep learning curve before giving up and selling the farm to us. Attempts they had made to outfit the farm as cheaply as possible yielded outbuildings and fencing already in a late stage of deterioration. A grove of nice old apple trees around the gardens had been debarked to within an inch of their lives. The tractor and hay machinery, of far higher quality when new than I had been able to afford in my commercial farming career, showed signs of mistreatment and lack of maintenance. Even in its present state of disrepair, it represented more of an investment than a farm with only 15 acres in fields could justify financially. I had grudgingly accepted it as part of the deal to seal the purchase of the property. From experience with worn out soils in NY, we could see in the varieties of vegetation on these pastures that fertility had not been rebuilt. Worn out soils are typical of abandoned farmland.

Neighbors who came to welcome us regaled us with stories of pigs, goats and chickens free ranging beyond the farm, which immediately confirmed our suspicions about what had damaged our apple trees. Stray chickens had ended their lives roasting on the fires in the adjacent campground, affecting neighbor relations in that sector. Clearly, the welcoming neighbors shared these stories in the hopes that we would do a better job that the previous occupants in keeping our livestock at home.

Property Development

Our general goals for living in Maine had been the same for decades: build a reasonable level of self-sufficiency in food production, water access, and energy capture, and live an active, satisfying life connected to the natural world. For us this meant restoring ecological health and productivity of a landscape worn out from farming that depleted soils, the same sort of ‘farmed out’ land that we had learned to restore while farming in New York state. Because farming had died out decades ago in this part of Maine, farming support services, both human and technical – resources that we had relied on in New York – were not available or far away and more costly. Our retirement income allowed us to afford the costs, but having been raised in the frugal tradition of New England, we were reluctant to invest in a project whose scale – limited by our declining energy with age – promised never to produce enough to financially justify the expense. However, the satisfaction gained from land restoration became its own justification, so we embarked on a project that would not always come up to the standards we knew were necessary.

Over a long period of education in ecosystem science and its application to farming, we had developed a method of holistic management that uses livestock in a key role in a farm understood as an agroecosystem. I have described the design of such a system in Human Designs for Ecosystem Management and Survival After the Oil Era. The most important principle derived from the way natural ecosystems work is to replace, as much as possible, external inputs with ones available within the system. Used holistically, livestock can provide food, fiber, soil fertility and draft animal power. Integrated with other organisms they can improve productivity and general carrying capacity of a farm. I had designed the farm in New York to use livestock in all these ways. On this less ambitious farming project, livestock still provide food and fertility.

Here in Maine, we have 20 acres of open land and 60 acres of forest. On it we manage a handful of sheep grazed in ways that improve soil fertility and forage production and quality. We cut hay for winter feed, build a winter barn manure/bedding pack and compost it, and grow mulch for several gardens. In the gardens we grow two dozen annual food crops and about a dozen perennials. And we cut all our firewood. Our well includes a hand pump, and a new pond ensures water for irrigation and livestock when well water is not enough.

Progress toward our land restoration goals is much slower than on our New York farm, due to the lack of farm services in a region that lost its farmers a couple of generations ago, and our declining energy to contribute farm labor at our retirement age. A key component of soil health and productivity regeneration is calcium, generally deficient in soils in the US Northeast. In actively farmed regions like New York, a phone call brought a truck to spread the necessary tons of lime over the fields. Here, such services are two hours trucking away. However, we soon learned that the local paper mill gives away lime as a byproduct, and we lined up a local trucker to dump the tons necessary to begin restoring calcium levels. We found a couple of old ground driven manure spreaders that we cobbled together into a working machine to pull behind our pick-up truck.

To reduce the lime spreading rate to a level the soil could handle (about 2 tons/acre) we wanted a source of manure to load along with the lime in the spreader. The imported manure would also help jumpstart the soil regeneration. As luck would have it, we discovered that the remaining dairy farmer in the neighborhood would give away his mountain of manure for the cost of trucking. So, for the first two years at least, we were able to economically jump start the process.

Grazing livestock, the other major component of low-cost farmland improvement, was also available locally. One of the rare remaining sheep farmers in the region, was happy to sell us females from his annual lamb crop. They were Katahdins (or at least a cross with that breed), a sheep breed created in Maine by crossing African sheep brought to the Antilles with a British breed, and thus a hair breed, and easier on the back because they shear themselves. Sheep husbandry with a mere handful of grazing animals as implements of land restoration slowed improvement of the open acreage, especially as we favored the gardens over the hay/pasture land with each winter’s bounty of composted manure bedding, but it kept farm labor requirements light in line with our retirement age energies.

The tractor that came with the property, oversized for the size of the farm, helps to dig out the bedding pack and spread the fertility.

But some hand labor is necessary.

A ten-year reckoning

Nearly ten years after the choice to resettle on a small farm in Robbinston, Maine, several thriving gardens produce three dozen fruits and vegetables, and the tiny sheep flock yields a couple of lambs per year for our freezer and several to sell to local customers.

In addition to the attached greenhouse, a cold frame dug into a slope and a free-standing greenhouse extend the growing season into winter on each end.

In the hard times coming, our annual harvest would go far to assure self-sufficiency in food. The main Achilles heel in the system is the machinery – tractor, haying equipment, chain saw, freezers, well pump, etc. – which will function only as long as the industrial economy delivers spare parts. As fossil energy depletes, the wheels are slowly coming off industrial civilization (see my explanations elsewhere). Hence, simpler technology machines and more hand labor will eventually have to replace these current labor-saving devices. One example that we have achieved so far is a pond near the top of the hill to gravity feed water to gardens and sheep as necessary.

In sum, the life we have made for ourselves here is satisfying, consisting of retirement farming, woodlot labor for firewood, continuing research into the ways of the world, pieces of writing like this one and occasional interactions with the natives.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Memoires, Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

August 23rd, 2021 at 1:06 pm

Hi Carl, Aug 23, 2021

I meet you at Bonnie Stewart’s place a.couple weeks ago. I researched Jon Berger a bit and listened to some of his lectures. Fascinating man.

I ran into Mark Wren at the Machias Blueberry Ball and asked him about you and your wife. I told him I wanted to get to know you both.

He gave me your last name and I found this interesting site that has so much great information.

I would love to drop by some time to meet Jane as well and get a tour of your farm.

Please let me know if you both would be open to me visiting your farm.

Sincerely curious to know more,

Robin Farrin