Scenarios of degrowth: an introduction to causal loop models

By Karl North | October 6, 2025

Prosperity in the Western world (aka the American Way of Life) has been in decline for decades, and no government since Nixon has done anything significant about it. Nor could they, in the long run. As any oil geologist knows, it is all about the end of cheap energy. All policies attempted simply to kick the can down the road. Or to lay false blame.

A useful scenario of the mechanics of degrowth based on the end of cheap energy is the post from Tim Morgan, https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/2020/11/23/185-the-objective-economy-part-two/. He shows how our consumption priorities shape a scenario of degrowth. A synopsis follows:

- Consumption has been “living on the life-support of financial manipulation”.

- As indebtedness reaches a saturation point, financial manipulation fails. Consumption declines.

- Degrowth in consumption starts with discretionary consumption.

- This depresses the whole sector of the economy that fuels discretionary consumption.

- The destruction of demand for debt follows the destruction of demand for discretionary consumption. Consumption declines further.

- All economic sectors dependent on consumption decline.

- This reduces income, lowering consumption further.

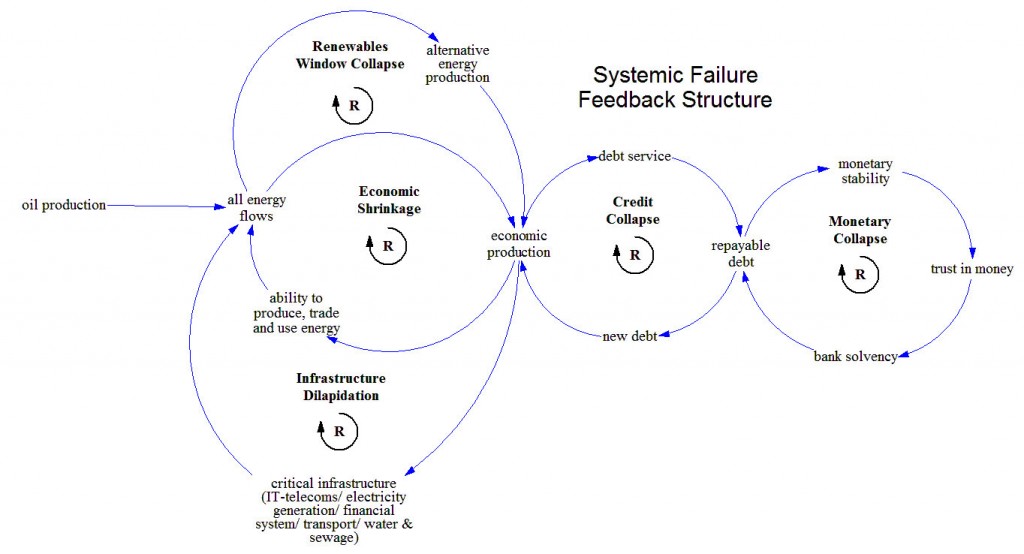

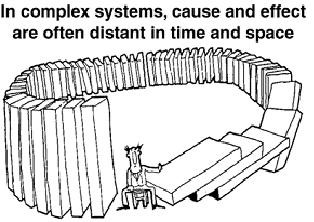

Causal loop models can help us visualize the dynamics of this degrowth process – how things change over time. Morgan’s scenario suggests a model structured as a positive feedback loop or two.

Causal loop models

Causal loop models are easy to read once the meaning of the symbols is explained. Briefly, the arrows tell the direction of causation between two variables. A positive sign means that the effected variable is changed in the same direction as the causal variable. A negative sign means that the effected variable is changed in the opposite direction from the causal variable. The label ‘R’ on a feedback loop means that change around the loop is reinforcing and causes exponential change over time. The universal name for this type is a positive feedback loop. The label ‘B’ on a loop would mean that the change around the loop balances or counteracts positive feedback. The universal name for this type is a negative feedback loop. I suggest reading the paper, Feedback Causality, which illustrates it in great detail with many examples.

A full model of any complex situation would include negative feedbacks that counteract exponential growth. In my partial model however, I think the following positive feedback loops are currently dominant in our society:

This model tells us how a change over time in the cost of energy affects our economy. Tracing change around the outer reinforcing/positive feedback loop: a rise in the cost of energy increases the cost of living and debt at all levels of society from consumer to federal toward a saturation point. This decreases the capacity of the financial elite to finance consumption, thus weakening the economy. As the economy contracts, income declines, raising the cost of living even more.

Tracing change around the inner positive feedback loop: a rising cost of energy raises the cost of living and cause consumers to forego discretionary consumption. This wipes out the discretionary part of the economy, thus reducing employment and raising the cost of living even more.

The above model elaborates part of a larger model shown below that summarizes how our society’s structural dynamics respond to the expected long-term rise in energy cost. You can test your model reading ability by adding signs to the causal arrows, then tracing change around the loops to understand how they work as reinforcing loops.

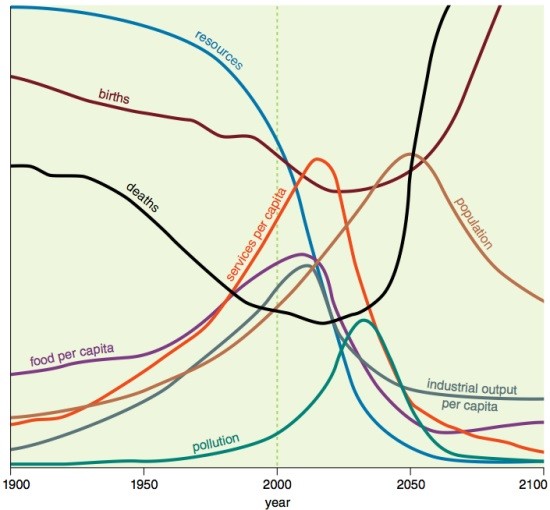

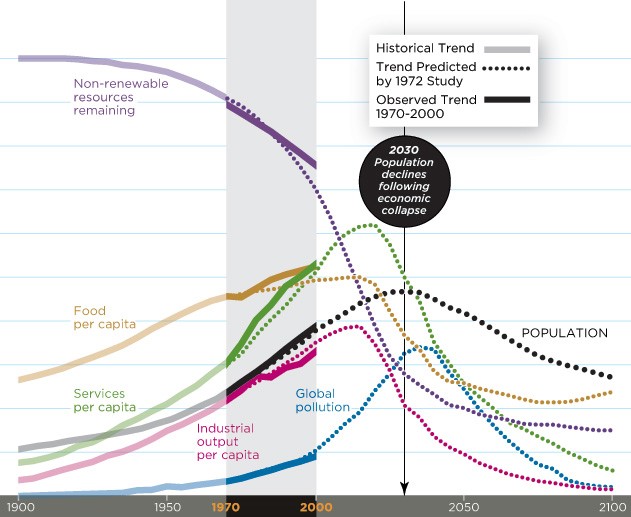

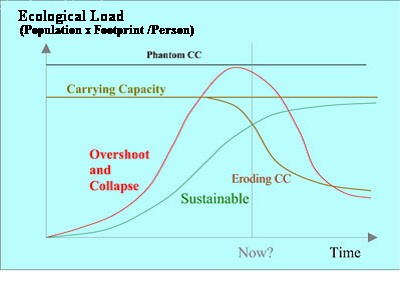

How useful are causal loop diagrams and the simulation models built on them? Over fifty years ago, scientists began applying the concept of feedback from engineering man-made systems to modeling the vastly more complex systems that we inhabit. With wider use, unfortunately many simulation modelers falsely assumed that the method could make accurate predictions, of which the method is not capable. Still, it allows us to study the complexity that arises from the interaction of many variables. It produces insights about the causes of the nonlinear behaviors this interaction generates, such as the rise and fall over time of the population of potato bugs in my potato patch, or even the rise and fall of a civilization.

Topics: Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

Can Western Global Elites Really Control their Endgame?

By Karl North | July 24, 2025

What is Pax Americana, defined in a single sentence? Pax Americana is a globalist parasitic regime that attempts to extract wealth from the rest of the world through the imposition of a transnational financial oligarchy backed by a system of worldwide military bases and an expeditionary force that exacts obedience through financial oppression and military violence. Its parasitism rests on two pillars: a monopoly on printing money and the ever-looming threat of horrible military violence. The US dollar monopoly (of which the rapidly declining Euro is a mere concession) was at first (right after World War II) backed not just by military might but by a large industrial base, huge fossil fuel reserves and more than sufficient gold. Over the intervening decades the industrial might has been whittled away and what now remains is a raw materials-based and agrarian economy with an overgrown services sector, all of it operating at a large and constant loss and accumulating debt at an ever-increasing pace.

- Dmitry Orlov

After a five-hundred-year run, the attempt of Western elites to exploit the planet’s peoples and plunder its resources has finally encountered three fatal obstacles to its agenda that have thrust the Western economies into terminal decline. The first is internal financialization and its exponentially mounting debt. The second is massive depletion of the resources that are essential to industrial economies, and mounting competition for the remnants. The third is competition from a multipolar alliance of nations led by China and Russia, who are determined to take back their sovereignty from the predations of Western hegemony. This essay will analyze the process of Western decline and contemplate its gradual replacement by a multipolar alternative.

Financialization

Financialization is self-inflicted: it is built into a political economy designed to allow unrestrained competition and a minimum of service to the common good. The result is a dynamic where, over time, economic contenders seek and achieve security in monopoly control by maximizing profit above all other goals. As this economic system globalized, starting over half a century ago, corporate and financial capital whose loyalties are only to profit fled the mature Western economies for more lucrative lands to exploit, leaving the West to deindustrialize until its growing peri-urban urban tent cities of homeless have come to increasingly resemble the renowned shanty towns of the global south.

Accordingly, the US-led Western financial elite has been exporting the industrial economies, first of the US, now increasingly of Europe, to more lucrative cheap labor foreign shores. The deindustrialization of the industrial sector has increasingly left the US as a warehouse economy distributing foreign-made goods. This solution presents its own downsizing challenges.

Many Americans live in a manufactured media bubble where no one mentions the deindustrialization of the US that has been going on for forty years. The rust belt in the heartland alone extends from the Great Lakes to Pittsburg and down to the Gulf. The latest presidential administrations of both political parties acknowledge it implicitly in their slogans. It takes enormous financial power to move the core industries of the last remaining superpower to another continent. The working-class workforce of these former core industries, demoted to low wage service industry jobs, is written off as “the former middle class”. Yet, few of us ask, “Who did this?” Instead, we want to believe that it was just an accident of history. The gradual impoverization of the Western working class is generating rising social unrest as they begin to question the economic system itself.

The question for Western elites became how to continue to squeeze profits from the dying core economies of the Western world while keeping the public pacified. One solution, at least for a while, has been to replace domestic production with imported cheap goods to by printing dollars to pay for imports. This has required foreign producers to accept payment in dollars, but the dollar as a viable currency is now under attack.

The other answer was to financialize Western economies – convert them from producing real wealth to rentier economies that extract remaining wealth through usury and debt. The goal of financialization, first in the US, then Western Europe has been to eventually buy everything up and rent it back to the previous owners. This creates a parasitic economy where these rents paid to the rich make the rich richer and everyone else poorer. Interest paid to the banker class on a US federal debt now at $37 trillion is growing exponentially.

But now the financial elite has painted itself into a corner. Raising interest rates to prop up the dollar currency is off the policy table because of all the debt that will be called in, which would crash the economy. The likely alternative is to hold rates low, which will make it impossible to control inflation. So, the goal will be to keep rigging the stats and the narrative to hold off perception of inflation as long as possible, to put off the tipping point where awareness rips through the collective consciousness. When that happens, hoarding begins and shelves go bare quickly, and hyperinflation occurs, savings evaporate, etc.

Downsizing Scenarios

The increasingly militarized attempts to sustain the Western empire are now risking WWIII, an external conflict that might downsize uncontrollably, perhaps in a nuclear exchange. The financial elite is now shifting its strategy to downsize the empire from within in a way that avoids class conflict by diverting blame from itself– a sort of controlled demolition. The first method chosen was the pandemic scam. This delivered the desired result – a sharp downturn of the economy that could be blamed on a virus. This could not work for long, so elites must cast about for new ‘natural crises’ to manufacture and sell to the public – the so-called disaster capitalism described by Naomi Klein. Examples: provoke disruptions of the now hyper-fragile global supply chains and blame them on China, use false flags of foreign threats to justify unaffordable serial wars, enlist climate catastrophists in a campaign to convert to impossible alternatives to fossil fuels.

One downsizing strategy appears to be the artful and imperceptible construction of a digital financial complex aimed to achieve totalitarian control. This would occur in a global economy Norbert Häring describes thus:

In 1997, when political scientist Samuel Huntington coined the term “Davos Man” to describe a global elite that “has little need for national loyalty, views national borders as obstacles, and sees national governments as residues from the past whose only useful function is to facilitate the elite’s global operations,”

To serve these goals, the power elite has captured the apparatus of the state by incorporating congress into the military industrial complex and achieving regulatory capture – control of all federal agencies mandated to force business interests to serve the public interest. This is typical under laissez-faire capitalism: economic sectors claiming to serve the public interest -the pharmaceutical industry, the weapons industry, industrial agribusiness, communications, scientific research, etc. – fall under monopoly control, becoming legalized rackets for shaking down the public. So, like the private-public partnership known as Japan Inc., the economic sectors under capitalism evolve into War Inc., Healthcare Inc., Agri-food Inc., etc. An example in the weapons industry of the capitalist pattern of putting profit before the public interest is the outsourcing of parts for weapons to other nations, especially to China, which puts US security at risk in case of a major war.

The deindustrialization strategy also has an Achilles Heel that affects US security interests. Downsizing the empire from within also achieves the goal of weakening its ability to beat up wayward client states that are increasingly seeking and declaring sovereignty. Even now, the Pentagon has acknowledged its inability conduct a major war.

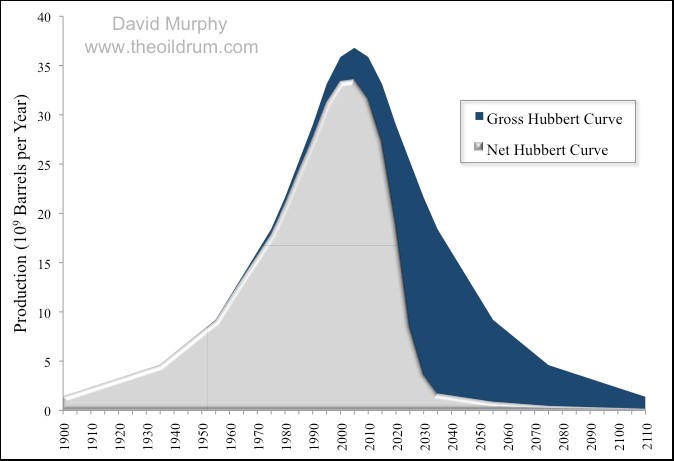

The end of oil

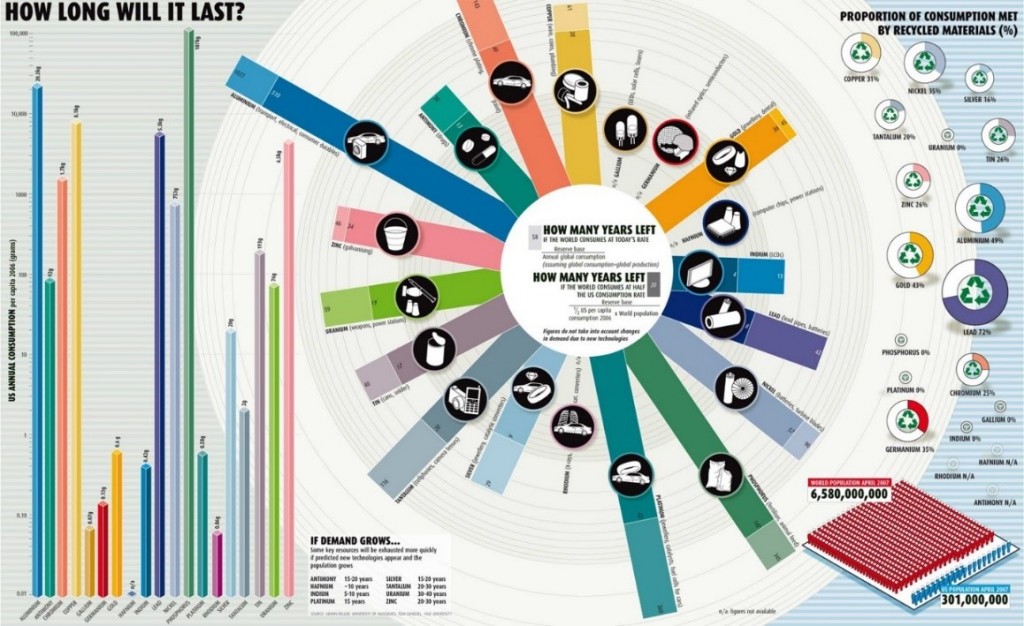

Underlying all the drivers of Western decline already mentioned is the massive depletion of finite planetary raw materials, of which the key resource is energy. This slow-moving disaster, like the undertow at the beach, is currently invisible to most people and, when pointed out, provokes vehement denial and fanciful solutions. I have described the end of the oil civilization and probable futures at length in other essays.[1] As one analyst of the collapse of industrial civilization describes it:

A bunch of mildly clever, highly social apes broke into a cookie jar of fossil energy and have been throwing a party for the past 150 years. The conditions at the party are incompatible with the biophysical realities of the planet. The party is about over and when morning comes, radical changes to our way of living will be imposed.[2]

This vision provokes important questions, some of which I have attempted to address in other essays.[i]

[i] An agroecological model for the end of the oil age

The quality of peasant life: a scenario for survival

Cities and Suburbs in the Energy Descent: Thinking in Scenarios

What aspects of our current world can and should be preserved? What are the possibilities of creative destruction as we enter the turmoil of the downslope? In the food economy for instance, the extreme domestication of plants and animals is so energy intensive that it must diminish in a post-petroleum world. As an example, the high production dairy cow, which is a cash cow for the corporations that monopolize the milk industry, is an extravagant energy consumer in several ways that are unlikely to survive the end of cheap oil. How will agriculture adapt to progressive undomestication? The persistence of denial prevents the public from taking such questions seriously.

Strategies of social control vs revolt

The information landscape in the West is owned by a power elite who have achieved full spectrum control over the narrative: via its deep state agents in govt, via the media cartel of a handful of mega-corporations, via corporate control of academic research funding.

As the lender of last resort, a wealthy and powerful global banker elite exerts control thru debt that is shaping Western societies in the modern age, reducing whole societies to debt slavery at all levels, from personal to governmental to balance of payments in international trade. It is important to understand that this phenomenon is not new and has deep roots in the history of Western Civilization, as anthropologist David Graeber (Debt: The First 5000 Years) and political economist Michael Hudson (…and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year ) document in what have become instant classics in the genre.

In ancient societies of Western Asia, a merchant class became wealthy from the lucrative trade from the Mediterranean across the region and eastward along the old silk road. As money lenders to the masses, they gradually reduced to debt peonage the farmers and craft people whose labor supported city states and rulers like Egyptian pharaohs and Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. People could no longer pay taxes and even ceased work when interest payments to the banker class consumed their incomes. Rulers whose regimes were threatened declared debt jubilees that reset all debts to zero.

Notice the parallel today as a US working class reduced to low paying service jobs by a banker elite orchestrated deindustrialization refuse to return to Bullshit Jobs (another Graeber book) after the plandemic lockdowns.

Graeber and Hudson chronicle a series of jubilees across the ancient world leading the emergent monotheisms, Christianity and Islam, to set limits on usury. As the West emerged from the Middle Ages, bankers again took control, fostering and financing wars between European monarchs and warlords, and keeping kings in their debt.

In the twentieth century, the international banker elite promoted the two world wars and the cold war, and quietly but openly financed the war economies of all participating nations. Banker control of information created a narrative of war hysteria and patriotic fervor that deflected attention from their use of war as a profit-making racket.

In recent decades, Western bankers created the IMF and the World Bank to offer investment opportunities to the nations of the global south that ensured their reduction to debt peonage. Confessions of an Economic Hit Man by John Perkins chronicles how this works. Leaders among the native elite who resist these bad investments he was instructed to turn over to the “jackals”, the real hit men, for elimination. There is a reference in the film The International to the jackals.

The solution in Western civilization that is in a deindustrialization process has been to replace production with debt-based imports. Unlikely to declare a Jubilee, how will financial elites confront exploding debt?

On psyops, false flags and strategies of desperation

An alliance of ideological collective myth makers and gate keepers – deep state agents of power elites, structured as an intel establishment core instructing policy makers, govt bureaucrats, mass media, science establishment and school teachers – build and constantly evolve official narratives to fit changing conditions. These works summarize the history and methods of the deep state:

The Secret Team: The CIA and Its Allies in Control of the United States and the World by L. Fletcher Prouty

JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy – Prouty 2011

Harlot’s Ghost by Norman Mailer 1992. 1300 pages

Faced with weakening imperial control, the deep state agents of power elites have resorted to strategies of desperation. A recent prime example was the disastrously failed color revolution to orchestrate the takeover of Ukraine, turning it into a Nazi police state aimed to terrorize and cleanse the country of its largely Russian population, which had been part of Russia for centuries. When Russia came to the defense of its people, Washington strong-armed Western Europe into cutting economic ties with Russia, a trade relationship that is essential to survival of Europe as an industrial economy. The crowning episode has been the recent sabotage of Europe’s energy lifeline to Russia, which appears to be a turning point in the demise of the West.

A fragile system

The history of Western Imperialism – whether economic, political, or cultural – shows that it cannot tolerate alternative civilizational models. The very idea of a civilizational alternative threatens a capitalist system that imprisons its population in wage slavery to private capital while skimming off profits of labor to an ever more wealthy and powerful financial oligarchy.

Some examples of the frightened reaction that exposed the hypocrisy of Western ideals are:

1) Faced with the Soviet alternative, the Great Depression and WWII begat a powerful socialist movement in Europe. Western finance hurriedly injected funds to finance the reconstruction under capitalist control (the Marshall Plan) and finally was forced into a compromise with organized labor in Europe that allowed ’social democracy’, a kinder, gentler capitalism, to emerge for a while to pacify the proletariat.

2) The CIA used mass murder to take down an Indonesian Sukarno regime, whose leadership of the global anti-imperialist movement posed the only threat.

3) It carried on a vicious economic warfare against any socialist experiment, such as Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua, no matter how small the country.

4) It suppressed for decades socialist China’s entry into the international community and the global economy.

5) Finally, the Trump administration’s mere articulation of previously taboo views and policy goals activated a weaponization, fully backed by the mass media, of the Democratic Party (and liberals generally) in repeated projects to destroy Trump’s presidency. This desperate action occurred despite the fact that the US deep state has so far easily neutralized any attempt on Trump’s part to carry out his expressed policy goals.

In Sum: Who rules the Western world, and how does that work?

Research has shown that over centuries a small set of banking families have accumulated a vast money power using usury (lending at interest). But that is only the top of a hierarchical structure of power relations, whose operation needs to be understood to answer questions like: why are elected leaders mandated to make policy so boxed in, so limited in the power that they can actually wield, as Trump obviously is.

Open exercise of power, as in ancient Rome, where the emperor sends out the legions to conquer territory and loot wealth, is no longer in vogue, to put it mildly. It has become clear to some analysts that in the modern world, power over decision making no longer flows down through a military type of chain of command. Hence, what has emerged is what is best understood as an inverse totalitarianism, where the chain of decision making is looser, the top players in the power hierarchy more obscure, yet in the long run still serves the financial powers at the top. The latter, as lenders of last resort, shape decision making of the major borrowers – the transnational corporations, which are the next level down the power structure. Decision makers at each level have some wiggle room, but not too much. The question that is important to ask is how do the interests of the actors at each level serve (or not) those of the banker elite.

In the US, the next level up from elected leaders is what has been called the deep state, a permanent shadow government that steers policy making as agents of big capital. The deep state as it is constituted today has a long history starting at least with the creation of the CIA after WWII. The function of the CIA, actually a wide network of operatives and assets, is covert and overt action to maintain and expand the US empire. But this imperial agency is only one of a tripartite alliance of convenience that also includes the military industrial complex and the Zionist power configuration, both of which are highly organized forces in their own right, and date back many decades at least. one can see the common interest of all three deep state elements at play in the creation and support of Israel.

The Zionist Power Configuration in most Western nations, backed by disproportionate Jewish wealth and clannish organizational power, have grown over the 70 years of the existence of Israel to serve as a tail wagging the dog of national governments that bends policies to serve Israeli interests. As an example, a shrewd Zionist pattern of campaign contributions to both major political parties in the US has assured almost total congressional loyalty to the Zionist primary interest, US support for Israel. Zionists include Israeli dual citizens who hold unusual numbers of high government positions and ownership of mass media. They stifle criticism with threats and accusations of anti-Semitism and increasingly with laws that criminalize anti-Zionist speech and even criticism of Israel. In the US, the large population of Christian evangelicals serve as willing foot soldiers for Israel in the electorate.

Individualism vs collectivism

What alternatives to the Western model are on the horizon, or are even possible? In America vs America Wang Huning argues that the true strength of a civilization lies not in freedom, but in cohesion, discipline, and purpose. He argues that when freedom becomes an absolute, it destroys the moral architecture needed for long-term societal continuity. In other words, the liberty that promised the future has annihilated it.

In the early 19th century Toqueville saw a US where:

- Individualism, while empowering, could become isolating, and dissolve traditional communal bonds.

- Materialism might replace spiritual purpose. Replacing other goals with desire for more stuff.

- Tyranny of the majority could suppress reasoned dissent.

In the US today, we can see that everything that Toqueville predicted has occurred, and created a society whose cultural beliefs and values are those of a decadent civilization.

The multipolar alternative

Wang contrasts the Chinese social tradition rooted in the insights of Confucious – humility over innovation for its own sake, acceptance of the status quo to conserve social order. The result is a modern China where networking advances knowledge better than the competition among private businesses standard in the US, and where long-term visioning contrasts with the short-term profit motive standard in the US. As the lead industrial economy in the emerging multipolar alternative to centuries of Western imperial domination, the current Chinese state policy of sovereign control over a mixed economy bears watching. The rise of a prominent private billionaire class in China puts it in potential conflict with the goal of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. The outcome of this conflict will affect the destiny of the world.

[1] Energy and Sustainability in Late Modern Society – the long story

The Industrial Economy is Ending Forever: an Energy Explanation for Agriculturists and Everyone – a synopsis

What props up the delusion of growth paradigm? – an analysis of denial

[2] N.J. Hagens. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800919310067#fig0030

[i] An agroecological model for the end of the oil age

The quality of peasant life: a scenario for survival

Cities and Suburbs in the Energy Descent: Thinking in Scenarios

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

Stories of my Life: A Swiss Scavenger Hunt

By Karl North | May 16, 2024

Joe Dassin was sweating bullets. He was scribbling frantically amid a pile of dirty coffee cups on scratch paper that he had covered with algebraic calculations. We were the only people in the Buffet de la Gare (train station restaurant) of the sleepy little Swiss border town of Chiasso, a couple of blocks away from Italy. Apparently this route south was little traveled in November.

Joe and I were trying to solve a quadratic equation that we presumed would divulge a telephone number which, in turn, would inform us of the next stop in a game that had sent competing teams of junior and senior class boys from two Swiss secondary schools on a four day adventure that was taking us all over the little alpine nation. The sole employee on duty in the station café watched us from his post behind the espresso machine with amused indifference. He had generously provided the paper napkins on which we were doing our calculations.

“Getting anywhere?”

Joe gave me a dirty look that said no. US high school algebra offered only brief exposure to quadratic equations; the experience had not stuck, and I had all but given up working on the problem. Joe, on the other hand was embarrassed. At the end of our senior year at École Internationale de Genève he was to pass his ‘first bac’, a French secondary school national exam that requires an educational level equivalent to at least two years of college in the US. Although we were the same age, Joe felt that with the educational advantage of his European schooling he should have solved this math problem by now.

Although he had lived on both continents after his parents had separated, Joe preferred his European persona. He was proud of his Paris accent, his superior European schooling and his well-traveled cosmopolitan life. His attitude to Americans like me who were just beginning to discover Europe was mix of condescension and friendly tolerance. We all lived on the same hall in the junior and senior class boys section of the small Internat, or live-in population of Ecolint as boarding students called the school, the École Internationale de Genève. Although he tried not to show it, he was disgusted to be teamed on this adventure with three Americans who barely spoke French and whom he could beat using only one hand at “baby-foot”, the European table soccer that we played constantly in the Internat day room.

At that point early in my year at Ecolint I knew little of Joe and his background. A gregarious guy, he had been at the school long enough to gain some serious status and advantages. As manager of the school’s high fidelity sound equipment he kept it in his room to play music whenever it was allowed, and even illegally after hours thanks to the acoustic insulation he had installed to hide the sound from the proctors. I saw that he also played the day room piano every time he got a chance. When he was not speaking French, he spoke with a perfect American accent in a school where British accents were the norm among non-Americans. Gradually Joe and I discovered enough of our mutual interest in music to form an a capella quartet and teach ourselves to sing black church classics like Go Down Moses, Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho and others. As such music was little known in Europe, we were asked to perform it in a school assembly where it was a great success. That was the start of my dawning awareness that Europeans appreciate African-American music far more than most Americans.

Only years later when Joe had become a French pop star did I learn enough of Joe’s extraordinary family history to be sorry that I had not known it at the time. Born in the US of American citizens, he moved to France only when his father Jules, a successful film maker, was blacklisted in the McCarthy witch hunts that destroyed many political, academic and artistic careers in the early 1950s. Jules Dassin’s films departed from the usual Hollywood fare devoted to the petty quarrels of the affluent classes; instead they celebrated the rough and tumble life of the US working class with a realism that the self-appointed censors of the witch hunt deemed un-American. Barred from work in the US, Jules found his film-making style embraced in France, but the move to Europe split up the family, leaving Joe’s mother back in the US. Jules Dassin’s great French success, Jamais Le Dimanche (Never On Sunday) gave him back his film career, and he married the star of the film, Greek actress and activist Melina Mercouri. After Ecolint, Joe tried college in the US, intending to major in anthropology, but eventually quit and returned to Paris where he acted bit parts in his father’s films and started his singing career.

Joe and I were tired. None of our team had slept in a bed the night before, the first day of the scavenger hunt, due to a move that initially put us ahead of all the other teams in the competition. It had ended in a fiasco that kept us from finding a hotel room and gained nothing on the other teams.

“Let’s get our Italy passport stamp and call it a day” Joe said regretfully. “We need to make contact with the other two, let them know we’re stuck and decide whether to call the emergency number to the game organizers and throw in the towel.” We walked the short distance to the Italian border on the edge of town, crossed over to get the Italian stamp in our passports, then turned back through customs to the Swiss side as the customs agents of both nations watched us with quizzical aplomb.

The creators of the game that we were experiencing called it Le Concours de Suisse. It consisted of a series of messages containing clues that sent us from one location to another across the country. In each location we were to search for clues to a new message that contained new instructions, usually somewhat hidden (as behind a quadratic equation!), that would send us on to other destinations. The adventure was designed to put teams of high school juniors and seniors on our own with a Swiss rail pass and barely enough pocket money to cover food and lodging for the duration of the game, to teach us teamwork and to let us experience a bit of Switzerland in a novel way by sending us traveling around the country to find the next clue to the next destination in the game.

Yesterday’s instruction had been to gather passport stamps from all countries that adjoin Switzerland and to solve the equation that would give us the clue to the next destination. Our team decided to split up the work, and the two brothers from Big Sur went off to Germany and Lichtenstein respectively while Joe and I went to the Italian border and worked on the equation. We were to rendezvous at a central point, the Buffet de la Gare in Zurich when we had each finished our part, which if successful would take us on the next step in the game.

But to return to the episode of the sleepless night. The first day, all teams started from Geneva. Each received a message directing the teams, at intervals so that teams would not meet, to the next location. The message was only a single proper name. Frantic research on our part finally revealed it to be the name of an obscure downtown café. We filled backpacks with snack food cribbed from the school kitchen and headed downtown on the trolley, an excellent system of public transport that went everywhere in the city and even across the French border to Annecy, several miles away. A search of the café at first divulged no clue as to the next message. We were getting anxious. Some of the café regulars eyed us warily, some with amusement. The juke box was playing. Curious about what music a Swiss juke box offered, Neal, one of the California brothers, looked over the titles.

“Hey, here’s a tune titled Ecolint!”

“Play it, for chrissake!,” yelled Joe. The bartender, in on the game, laughed. Bingo. The message in the tune directed us to the next location in the game, a castle in ruins on a hill overlooking Sion, a town over a couple of hours away by train in the upper Rhone valley beyond Lake Geneva. For a while we relaxed, enjoying from the train window the spectacular alpine vista across the lake.

By the time we reached Sion in the upper Rhone vineyards and hiked up the side of the valley to the castle, all the other teams were already there, busy trying to decipher the next message. It was a message in code from car headlights located on the other side of the valley. No one was getting it. I looked at the blinking lights. It had to be Morse code.

“I can do this!” I exclaimed. In an earlier teenage obsession with electronics, I had built some amateur radio equipment and learned enough code to get the legal license to operate a transmitter. I quickly repeated the letters I saw in the lights to a team member, who wrote it down and read off the message to the rest of our team, huddled in secrecy away from the other teams. The message was simple: “Come to the lights”.

We agreed on a plan to sneak off quietly like we’re going back to town, then short cut directly down across the valley toward the car headlights. We jumped fences and crossed vineyards whose grapes, I learned in later life, made some of the best red wine in Switzerland. Unfortunately we had not counted on an encounter with the Rhone River. When we reached it, there was the car on the other side, still blinking its Morse code. But no bridge. We were the first team there, but on the wrong side of the river. By the time we bushwhacked our way through the fields to the only bridge, which was back in town, and followed the Rhone to the car, it was nearly midnight. The organizers – our teachers – told us all the other teams had finally read the message, come to the car (the right way) and returned to town to find hotel lodging. We were the last, and they were tired of waiting.

“What took you so long?”

They shook their heads in weary amusement at our story.

“You might not easily book a hotel room this time of night.”

They were right. Swiss rural towns run on rigid Calvinist clockwork like the trains and most everything in Switzerland. The town of Sion was closed and locked for the night. No one would answer our knock at any hotel door. Quelle fiasco! The only building open was the train station, where we thought to spend the night sleeping on the waiting room benches. At least we would be out of the increasingly frosty November night. No sooner had we settled on the waiting room benches but the station master woke us to say that the station was closing until 6 AM and sent us back outside. Next to the station were two brightly lit phone booths, almost the only lights in town at that hour, but not locked. We split up, two to a phone booth, and survived until dawn on shared body heat and food we had brought.

There’s not much left to tell about our scavenger hunt story. Joe and I shot much of our stipend on a good dinner and lodging in Chiasso. He introduced me to café kirsch, a Swiss version of a potent combination of caffeine and alcohol that is common in Europe: café cognac in France, café schnapps in Germany.

My initiation to café kirsch was an early, albeit minor example of a long series of encounters with European traditions whose historical depth and richness stretch back centuries and rest on a foundation in the ancient civilizations of the Orient and India. Over the years I experienced a growing awareness of how little of these traditions and their accumulated wisdom crossed the Atlantic in the mental baggage of Europeans who colonized the New World. As I gradually discovered, many European traditions reveal a time-tested maturity that lends them a quality that I rarely see in their US equivalents. I see this quality across the whole range of European culture, be it culinary, architectural or agricultural, or less tangible but more important, in customs of social and political interaction and in a sense of the importance of history to an understanding of the present. Why did the emigrants to North America see so little value in these traditions that they left so many of them behind? Of course the incessant material expansion that marks the American Way of Life fascinates Europe, but as they know from history, it takes more than physical wealth to build a civilization. Now, nearly 60 years after my Swiss introduction to Europe and after ten years living and working in French-speaking countries, I see more than a little truth in the view common on the Continent that the US is still an infantile society.

We reconnected with the rest of our team in Zurich the next day. Knowing we had already lost the game, we enjoyed a leisurely brunch in Zurich’s train station Buffet de la Gare which, often like the trains themselves, offered three classes of service, a concrete example of European class structure. My still vivid recollection is that even in the third class restaurant where our meager finances confined us, the quality of the service was impeccable, and eye-opening for me – white table cloths, silver dishware, hovering waiters, etc.

We were the only team to fail to finish the game. That did little to dampen our exhilaration at the experience of four days on our own, traveling sometimes on quaint little trains on narrow gauge rails that negotiated tunnels and sheer drops through magnificent Alpine scenery, frosted with the first snows of the season. As a team, we had seen bits of five countries, and had a lot to share.

Topics: Memoires | No Comments » |

Watering the Garrotxes: donkey farming in the French Pyrénées

By Karl North | March 7, 2024

A region of distinction in decline

French Catalonians commonly call their region Roussillon, but as one ascends from the coastal plain that stretches from the city of Narbonne to the Spanish border, first into the foothills, then into the narrow, steep-sided Tet river valley known as the Conflent, different landscapes take on different names. The last town with shops up the N116 national highway for 20 km. up a mountain gorge is Olette, population 600, where Larisa, my youngest child, received most of her elementary schooling. (Parenthetically, unhappy after her first exposure despite being ranked at the head of her class, Larisa quit school. After taking a year off playing in our mountain village with smaller kids, she reconsidered, and decided to return to her position as sole “étranger” in her class.)

A right turn off to the north from Olette takes one into the valley called Garrotxes, some of which borders on the township of Canaveilles, with its partly abandoned village perched at 3000’ along a ridge overlooking the Tet valley, where our family lived for most of the 1970s. Most of the rugged mountain terrain of the region had been under a variety of more or less intensive management until the end of subsistence farming communities circa 1960. But a decade later after the younger generation had left the mountains seeking an easier life, most of it had rewilded, and the locals called any wild place the garrotxes, which means “ the sticks” in Catalan.

Besides a school and a gendarmerie, Olette sports a restaurant, a café, a tabac, a pharmacy specializing in herbal cures and significantly, two dueling butcher shops. The family budget rarely allowed us to patronize either, even for “boudin”, or blood sausage, the cheapest next to tripe. However, the school sent its pupils to the restaurant, whose menu, created for the summer tourist trade, boasted local stream-grown trout and lamb chops, so my children ate meat daily.

Olette’s other distinctive landmark is its church, really a small cathedral, presumably because it was built to serve a wide region of mountain communities. Like most churches in a long-secularized France, it stood practically empty most days. Its young priest, Joseph, one of the three sons of the Flemish family Reymaakers (sp) who had relocated to the valley of the Garrotxes a generation before, was known locally as the hippy priest, for various reasons. One was his attractive assistant catechism teacher, who was rumored to be his girlfriend. Also, as young urban refugees began to filter in during France’s belated version of US sixties counterculture, Joseph, reduced mostly to circuit riding through the mountains, made several attempts, mostly rebuffed, to help the marginals, as they called themselves, settle in to mountain living. This put the priest in the unenviable position of mediator between the locals and the newcomers, who the remaining locals viewed as urban lightweights who would never last in a terrain so challenging that it had driven out most of their children.

Midnight mass on Christmas eve was one of the few times in a year when the Olette cathedral was packed to the gills, despite competition from the café, which held a rousing, inebriated bingo fest for the anti-clericals, a large population in southern France. Apparently, Joseph had learned that I had been studying classical guitar for several years, and decided to recruit me for a solo performance during the midnight mass. My little Bach prelude was reasonably successful, more because it was such a novelty at the annual midnight mass than for the quality of my playing.

Actually, my meager musical talents leaned toward choral singing and directing, so I offered to create a quartet to enhance midnight mass the next year with four-part harmony. In addition to my wife and myself, I recruited Helleke, a musician from Antwerp who lived in Llar, a hamlet in our township, in a house restored by one of Joseph’s brothers, whom she had married. I found a soprano to complete the quartet at the weekly farmers’ market in Prades, a meeting place of young newcomers to the region.

Looking to beef up the midnight mass that year, the priest was building what he hoped was an authentic Nativity Scene in the nave of the cathedral. I offered to lend my donkey, who was so old that some good hay next to the manger of the Christ Child would be enough to keep her stationary during the mass. The idea excited the priest at first, but then he backed away from the idea, fearing unexpected consequences.

Our quartet sang from the church gallery, hoping to sound like angels from the sky. The Reymaakers patriarch, a devout Christian who had built his own chapel on their farm, a promontory over looking the valley of the Garrotxes, voiced his approval of our choral performance as we exited the church after the mass. Hopefully this mitigated his unhappiness at the hippy priest reputation his son had gained, partly from fraternizing with us marginals.

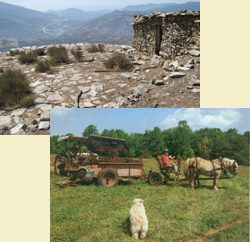

A backstory

In the attempt to flee responsibilities of citizenship in a country that had used weapons of mass destruction to commit genocide and horrific environmental damage in poor, Third World countries of Southeast Asia, in 1973 I left an academic career path and moved with my wife and school-age children to begin an agrarian life in the small village of Canaveilles in the mountains of French Catalonia. The houses of the region, with their thick stone and clay walls and heavy slate roofs, are a testament to a bygone age of heroic struggle and tenacity in an intensely sunlit but difficult terrain, using primarily the simple materials that the mountain offered in abundance. Nearly abandoned after centuries of peasant subsistence farming, the village of Canaveilles, located at an altitude of 3500 ft, offered one of these houses and a barn, all attached to other houses in the clustered style of villages of old Europe. We bought the house and barn next door and began to rebuild it as we learned to farm the narrow terraces of the steep Mediterranean mountainside.

The irony of such a change of vocation was that my choice of social terrain, like the other dying peasant societies of the world, had become the intellectual focus of the anthropological discipline that four years of graduate school had trained me to study. However, having just escaped from an anthropological career, I was in no mood to consider the research possibilities of the remnants of Catalonian peasant life in my midst. Still, I suspect that the vignettes in this account cannot help but suffer from a residue of my previous intellectual life. Be advised, readers!

Canaveilles house and barn with solarized third floor and balcony

A first solar design experience

The house offered some ideal requisites of passive solar design. The front wall had full southern exposure to the intense sun of the region, but being two feet thick, kept out the both summer heat and the freezing temperatures of winter nights. The earth sheltered house has long been a favorite of energy efficient house designers. This house, in fact the whole street, was as if built to order. The north wall, chipped into the mountainside, provided the insulation equivalent of an endless earth berm. The side walls, shared with the neighbors, also supplied the high insulation values that are necessary to passive solar design. The mountainside behind the village sheltered it from the prevailing winds, including the Tramontane, a cousin to the dreaded Mistral, a three-day gale that often sweeps down the Rhone valley.

All these elements in combination with the forgiving Mediterranean climate – shirtsleeve temperatures on cloudless winter days – reduced the heat requirement and made our first solar design project easier. Compared to recommendations for thermal mass in the passive solar literature, the centuries-old, massive stone walls of this dwelling were overkill. And our rule of thumb learned in practice has been to cover as much of the south side of a house with glass as we could afford, then build in enough heat storage to handle the excess solar capture capacity of the south glass area.

Building on these advantages, we decided to raise the low garret third floor to become the main living space and glass in the front. Constructing the new living space was an exercise in the use of free and salvage materials, for our finances were no better than those of the remaining villagers. The river bank in the gorge below the village supplied free sand for the mortar to raise the walls. Wall stone came from ruins in the village. Rights as property owners gave us access to timber for beams and rafters in the village communal forest. Work parties of volunteers from around the region helped place the big beams, and helped with the heavy labor of removal of the old slate roof in exchange for room and board. In an abandoned commercial building in the region, we found windows at salvage prices, but large enough to be used as French doors, and installed them as the south wall of the living space. I include these details because they illustrate a low-cost approach to building (and to life) that will become increasingly necessary in the post-petroleum era.

The resulting passive solar renovation reduced firewood needs to less than a cord, which we could easily skid down behind a donkey from the forests above. We burned it in a small cookstove augmented by a fireplace I constructed in the local tradition, using a chestnut beam salvaged from the expansion of one of the Olette butcher shops. The chestnut was so old and dense that it struck sparks from the chainsaw.

Having been brought up in wooden houses, we found the experience of living within the permanence, security, and quiet of massive masonry walls unforgettable. Similarly, the feeling of being almost outdoors that the wall of French doors conveyed, in combination with the balcony just outside affording a spectacular panorama of a gorge rising to often snow-capped peaks, made living in the renovated house in Canaveilles a special experience. The 10000’ peak in the picture, eastern anchor of the Pyrénées range is visible from much of Roussillon. Called the Canigou, it still retains some of its sacred quality in the region. Houses and even whole villages orient themselves toward the it if they can, and when villages celebrate the summer solstice with bonfires throughout the region, volunteers climb the Canigou with firewood to celebrate the solstice there.

Donkey farming

To survive on the south face of a mountain in a Mediterranean climate, human communities had to initiate seemingly superhuman changes in the terrain: stone-walled terraces on which to build a village and grow food, and an irrigation canal cut into the mountainside for ten kilometers back along the ridge to meet the Tet river at 5000’ altitude at the city of Montlouis.

Flatlanders hoping to last long in this environment face a steep learning curve of physical conditioning, where almost every activity includes a stairway up or down. My survival plan started with growing gardens and animals for food, skills in which I had some elementary experience. After surviving the vicissitudes of cooperative projects with unreliable partners, we had learned enough to be mostly self-sufficient on our own. But growing anything required running up and down the mountain to direct irrigation water to fields and gardens, and to graze the dozen ewes and their annual lamb crop in pastures at different altitudes depending on the season. I needed to manure upper terraces, skid firewood and hay down to the village, and climb to the summer pastures.

I decided we needed a donkey. We also needed to acquire farmland to gain residential rights and benefits, both in the village and in France. As it happened, my friend the horse butcher, who held the second largest property in the township (after the mayor), managed to provide both. For $10 he offered me the aged donkey he had planned to slaughter, and for $75, annual rental of all his land, which gave me full irrigation rights.

The horse butcher delivered the rescued donkey, a coal-black animal, to me in the village at midnight, presumably after one of his regular drinking bouts, so I called her Mitjanit, ‘midnight’ in Catalan. I adapted some pieces of abandoned harness to allow Mitjanit to carry me, pull a travois (later fitted with wheels) and skid firewood tree trunks. At this point I thought we were equipped to begin to grow most of our food on the terraced mountainside, except for water.

Watering the Garotxe

Societies that depend on irrigation systems are so distinctive that some anthropologists have called them hydraulic civilizations. I discovered that this was true even at the small scale represented in the township of Canaveilles. Common to all such societies is a need for a water administration that maintains a complex man-made irrigation system and polices the sharing of water among the users. In our village it consisted of a committee elected by the land owners who had irrigation rights and a person hired each year to manage the canal and distribution of its water. The committee collects a tax from the users to pay for the annual cleaning and repairs, and to pay the canal manager. The cleaning crew often consists of users whose pay defrays the tax. Cleaning occurs in the early spring, after which the system is open for the growing season.

Like our village in the Pyrénées, small communities in the US south west created similar systems centuries ago. My wife and I once spent a month working on a farmstead on the side of the Sierra Nevada, a mountain range in Andalucia in southern Spain, watered from an irrigation system that dated back to Roman times, which the later Islamic civilization greatly refined.

Also characteristic of irrigation civilizations is the social bond the need for water creates, along with endless feuds over its management. This bond can be stronger than anything else that binds the community, including politics or religion. In Bali, religious control of water dropping through a series of rice paddy terraces has created a system that has lasted a thousand years, administered by priests in water temples erected at different levels of the irrigation system.

When our family settled in the village in 1973, the irrigation system suffered from lack of help. The year-round residents consisted of Parisian couple exiled to south of France as penance for having collaborated with the Nazis, a couple from the coastal plain who had fled a grocery scandal, and the only remaining local, an old woman who kept to herself. Both families included a married child and small goat herds. Until we arrived, only the Parisian actually needed the canal water for his gardens from the seasonal canal. Two spring developments with their troughs at each end of the village originally provided water for the residents. Now a cistern above town caught spring water and piped it to the houses. But without infiltrated water from the irrigation system all these springs dried up in summer. So everyone, including the summer people who still had ancestral abandoned irrigation land and paid the water tax, needed the canal to run.

The village water supply had not always depended so heavily on the canal. According to the Parisian, he was now the acting mayor because the elected mayor had sold the water rights to a hydroelectric company in return for a cottage and lifetime employment in the company down in Olette. The company had dug tunnels under the mountainside that drained the water, permanently lowering the water table. Another simmering scandal.

My first spring in the village found me learning to clean the canal with an unsatisfactorily small crew, most of whom were experienced locals who looked with disdain on the foreigner and chatted mostly in Catalan. The cleaning started at the head of the canal, which at 5000’ was still in wintry weather. As we worked for a week along it toward the end at 4500’ over the village we thus experienced an enjoyable rapid change of season. Half way along a shelter had been built shaped like an igloo of rocks gradually closing in at the top. Built on a promontory jutting out from the ridge, it offered a beautiful view of the Tet valley in both directions. The day the work party neared the shelter, I decided to bring bedding to camp out. The locals tried to scare me, saying the rock cabin was infested with vipers. I said I would take my chances, since unlike the rest I would not have to hike in and out for the next two day’s work.

Water wars

After its long, perilous itinerary cut into the side of a steep ridge, the canal proper ends far above the village in the summer pastures. Then a branching system of “rigoles” descends to eventually serve every property holding irrigation rights. A main split occurs where a large piece of shale with two equal holes set vertically across the rigole sends water into separate watersheds. Stories abound of blood shed at this location when angry irrigants hiked up, only to find one hole unlawfully blocked. Indeed, early in my adventure in learning irrigated agriculture I encountered a blocked hole at the fateful site. When I confronted the Parisian, who was the only other irrigant in the village at the time, he blithely suggested that debris floating down from the canal must have blocked the hole. Later, a water feud erupted between Canaveilles and Llar, its sister hamlet upstream, when the gardeners at Llar diverted the whole canal into their fields for a week. This provoked heated phone talks from the Parisian, who was the canal manager that year, to culprits at Llar.

Water supply was only one of the challenges encountered in the attempt to feed our family from our crops. A large planting of potatoes destined to feed ourselves and a couple of pigs as well suffered a heavy infestation of potato beetles despite good irrigation that year. The problem was that the soil was too depleted to grow a crop that could protect itself from the predators. I was to encounter the same worn-out soil later while reclaiming abandoned fields in upstate New York, and again when I restored a small farm to retire on in the state of Maine. (Eventually I developed a soil regeneration complex that integrated management-intensive grazing to maximize grass productivity and soil organic matter, and careful manure management with a bedding pack and composting to retain nutrients. The system I evolved is described in Illustrations and Challenges of Progress Toward Sustainability in the Northland Sheep Dairy Experience).

A number of other growing experiments failed or suffered from an unreliable water supply or predators ranging from insects to wild boars. My most successful food source became the gardens in the terrace just below our house and adjoined sheep barn. They benefitted from a compost pile from manure dug out of the barn and thrown over the wall, and from water I diverted from a rigole just above the village, using a garden hose and a filtered funnel. One of the gardens, located in a barnyard manured for centuries, well-watered in the hot Mediterranean sun, grew the largest yield of potatoes that I have ever produced. Crops in upper fields occasionally did well, but required the donkey Mitjanit to climb up through the terraced fields transporting compost, a job she knew well but did not relish at her advanced age.

Marginals and their Discontents

Like most of their counterparts in the US, European back-to-the-landers that I encountered arriving in numbers in the South of France in the 1970s were ill-equipped for life on the lam from urban civilization. Attracted to the sunny Mediterranean and its abandoned villages, a few with manual skills set to work restoring crumbling houses and barns. Even fewer had any notion of how to grow their own food. Others just sat in the sun until their cash ran out.

Two enterprising marginals I befriended succeeded for a while. One couple, after bouncing around living in caves and borrowed municipal buildings, purchased a property high above Canaveilles that provided a year-round spring and easy access to the road from the village up to the summer pastures. They built a little cabin and created a small grass-fed rabbit project selling dressed rabbit to the butchers at Olette. We shared machines – they borrowed the tiller the horse butcher had loaned me and I used their chainsaw. As we both were on a steep learning curve in machine maintenance, the implements suffered considerable damage at first. Then, wanting to enjoy aged pork, a delicacy of the Mediterranean that I had discovered on a student year in France, but little known to most Americans, Bernard, the husband, and I began a cooperative pig project. When we drove down to the seacoast to buy two sows, sensing something amiss, I asked Bernard if he had brought cash for his half of the deal. No, he confessed he expected me to pay for both, then agreed reluctantly to reimburse me. After a few days he abandoned the project altogether, leaving me with two big sows to feed. The pitfalls and joys of my pig project warrants its own story that I will tackle later in this tale.

The other couple, well capitalized Parisians, built a goat dairy lower in the Tet valley on relatively flat terrain, acquired hay lands and machinery, and made excellent cheese, all of which sold well at the weekly farmers market in Prades. They were gregarious, getting to know many people in the region, and hiring other marginals to help with haying and other chores, They introduced me to people at the local monastery, which was hosting several artist refugees from fascist Spain. One, a muralist, gave me my first sheep dog, a half-breed that we named Milou. The daughter of another refugee became my student when I had started giving introductory lessons in classical guitar. Eventually we began trading whole wheat bread my wife baked for gallons of milk from the goat dairy, thus adding a relatively cheap source of dairy to our diet. Their goat dairy, while successful for a while, languished when the husband got bored, retreated into his cannabis oil heaven and left all the work to his wife.

Cattle Wars

French fascination with the life and legends of the American far west – its cowboys and Indians, its cattle rustling gangs and the posses formed to fight them – has outlasted anything surviving in the US itself. An investor group in the north of France saw the chance for a low-cost cattle ranching scheme. Calling itself La Compagnie de la Californie, it made a deal with the mayors of our village and a neighboring township to put hundreds of cattle on our mountains under the management of a single, low-paid herdsman. Since the cattle were pastured on private property as well as municipal commons, the company sent letters with paltry rental payments to the land owners. The barely managed herd ranged far and wide, breaking down centuries-old terrace walls, rampaging through our crops and village streets, and many dying from brucellosis, which was still endemic in the region. The scam was justified as forest fire management, a legitimate concern in the no longer grazed grasslands and forest of the mostly abandoned townships.

As it happened, recent fire had occurred in our township. Presumably from the cigarette of a passing motorist, the fire raced up the steep forested mountain, burning mostly understory brushwood. The Parisian and I were able to stop it where the forest joined the summer pasture, and little was left to do but stamp out small fires in patches of thicker underbrush. The local fire brigade arrived in their elegant uniforms just in time see the last of our fire fight in the now smoking hillside.

Meanwhile, along with arrival of the cattle herd, our village and the whole region had seen an influx of marginals, including several households just in our village, who had begun to use the land for their crops and livestock. I was growing crops and pasturing sheep on property I rented from the horse butcher, second only to the mayor in the size of his holdings. The local gendarmes, regarding the marginals as rootless riffraff prone to cause trouble, were slow to respond to our repeated complaints of cattle damage. The mayors, fearing the loss of their cut of the cattle profits, fought back.

The chosen setting was the secluded little hot spring at the edge of the Tet, a quiet stream at that location. Offering both hot and cold bathing, it saw frequent visits by marginals, whose restored peasant dwellings had never included bathrooms. One day when a large group of us from the village hiked down to the hot spring, someone alerted the police, who appeared suddenly on the other side of the river to announce that our group, which included mothers and babies undressed for the bath, were under arrest for “atteinte à la pudeur publique”, or assault on the public’s chastity, a difficult crime to pull off in an isolated location never visited by any but a rare passing trout fisherman. The immediate outcome of this comic caper was a day the group had to spend at the Gendarmerie d’Olette, while embarrassed police watched mothers nursing and changing diapers on office desks. Finally, they dismissed us to await trial at the regional capital, Perpignan near the seacoast.

Convoked to stand trial many months later, the group discovered that the father of one of the young mothers, a successful apple orchardist in our vicinity, had engaged a lawyer. In our defense he exposed the hypocrisy of a justice system that prosecutes bathers in a secluded gorge while allowing Scandinavian vacationers to cavort naked on the beaches of Roussillon, presumably because they benefit the local tourist economy. The judge ruled us guilty with suspended punishment.

The cattle war accelerated, gaining the attention of local leftists who, to my surprise, often dominated politics in rural towns in the south of France. In our support they organized an attack on the government agency that had sold land to the cattle cartel, thus giving the cartel a foothold in our township. Government hearings revealed gross mismanagement, which weakened the Compagnie de la Californie and forced some reforms. Twenty years later when we returned to Canaveilles for a visit, the cattle cartel had disappeared.

Adventures in Jambon Land

Any farmer who manages to produce more than his family’s bare subsistence knows the value of a pig. Beyond its value as food and cooking fat, this omnivore exists to conserve in its body anything the farm produces that cannot be immediately consumed or sold. The same way livestock of all kinds have functioned for pastoralists for thousands of years, a pig serves as a living piggy bank, a savings account to draw on in times of need. And like the interest rate in a bank account, a sow can make piglets.

Even more important, almost all parts of the pig can be preserved without refrigeration, by salt curing and ageing for as much as a year or two, and whose flavor in my view is superior to cooked pork. Because the process cures the meat of trichinosis, the parasite that has caused Islam and Judaism to prohibit pork, aged ham has long been the cornerstone of good eating in the Christianized areas of the Mediterranean.

Having experienced the fine flavor of aged, uncooked ham during previous trips to the region, I decided to learn how to process a pig. Francis and Francoise, a younger couple who we helped construct makeshift living quarters next to our donkey shed, eagerly agreed to split the cost of a pig, as Francis’ family had relocated to France from Spain, reputed to produce the highest quality cured ham.

An expedition up the valley to La Cerdagne, a hanging valley at 5000’ whose large farms could afford to grow extra pork, netted us a 250 lb. animal. As luck would have it, the Figuères, an elderly couple who spent their weekends and summers down the street in their ancestral home, agreed to teach us the processing skills. Monsieur Figuère’s trade as a driver often included pig slaughter as a side enterprise. On the appointed day we gathered the specialized tools, all of which had come with the purchase of our property – a wooden trough in which to scald the pig and loosen the bristles, a cast iron cauldron to boil the water for scalding and later to cook the blood and white sausages, scrapers made from pieces of a broken scythe blade. We had been instructed to get up early to build a fire under the cauldron.

Monsieur Figuère brought a crucial implement – a wood handled steel rod with an arrow shaped end bent around into a hook. Inserted under the jaw, the pig was under complete control, and was quickly placed on the upturned trough for bleeding. My wife then received instruction in the wife’s traditional duty, which was to catch the blood in a bowl and stir it to prevent coagulation. The bled pig was placed in the trough with boiling water, scraped clean of bristles and dehooved with the hook. Then it was hung, gutted and split along the backbone. While the carcass was cooling for butchering, Mme Figuère fed everyone a lunch of the organ meats and aioli, the local garlic mayonnaise.

We spent the afternoon cutting and preparing fatback, hams and sides of bacon for salting, cutting the rest for grinding into sausage, and cleaning and soaking the intestines in the upper spring (la Fontaine) for stuffing. The next day the horse butcher ground the sausage and lent us his stuffer, and we spent the rest of the day salting and stuffing. After curing time, which varied from two weeks to a month, we enjoyed months of home processed animal protein.

Now we knew how to make ‘jambon de montagne’, the next project was to grow our own pork. Left with two large, hungry sows from the fiasco of the pig cooperative, the extra potatoes, mangles and wheat that I had grown began to disappear quickly as we boiled it into pig feed in the cauldron, a traditional way of making pig feed in the region. I tried to add garbage from the tourist restaurant and spa down next to the main highway, but separating the edible from other trash was soon too much work.

The butcher I knew as a customer for my lambs was slaughtering over a dozen lambs twice a week at the municipal slaughterhouse in Prades and throwing away most of the guts, so he let me spend the morning cleaning them in the stream running through the building and take a trash can of tripe home to add to the pig cauldron. A delicious aroma from the resultant stew permeated our end of the village. We even fished out some of the tripe to try ourselves. The carnivorous diet made the sows begin to eye us as food, and we were reduced to quickly throwing their feed into the trough and making an escape.

Our next project was to make piglets. I loaded Virginia Slim, the more friendly sow into our truck and drove her down the valley for a couple of weeks of mating with a boar. The eventual result was an oversize litter of 11 piglets, from which we were able to save only enough for the sow’s 9 spigots. The sale of weaned pigs at a livestock market day in Olette was a net loss except for the two the goat dairy bought, deciding us to end the pig project and convert the sows to jambon de montagne.

Liberated Ecclesiastics

In a Europe where a secular age had emptied the churches, ecclesiastics at loose ends cast about for new flocks with which to ply their trade. The challenge of the unemployed ecclesiastics expressed itself in our locale in two ways. Joseph, ‘the hippy priest of Olette’ who I introduced earlier in this account, tried convoking local marginals to a dinner get-together where he hoped to give some direction to their sudden appearance in his Parrish. The marginals rebuffed his efforts with reactions that ranged from amusement to anticlerical disdain. Joseph also rounded up budding juvenile delinquents and other street kids from the coastal towns for a day trip in the mountains to assist our spring canal cleaning. The locals on the cleaning crew, even more anticlerical than the marginals, were openly sarcastic all day. As one remarked in an aside, priests are the people who wear skirts (at least still when saying mass) and don’t work for a living.

The other manifestation of clerical liberation struck closer to home. On settling our family in Canaveilles we discovered that the meager village population included a resident nun. Frustrated with quiet convent life, Sister Marie-Christella had ventured out into the fast-changing world. She had adopted our village as her terrain of battle and launched a project to bring it back to life. As one of her first ventures, she obtained our use of an empty house and barn as temporary living quarters and midwifed negotiations with the distant owner for its eventual purchase.

As the village marginal population swelled, she focused on its children, first bringing them clothing from church charity donations. Then, to celebrate the village’s annual saint’s day, she trained them along with others from Olette for a grand performance in the village plaza of dances from different French folk traditions, replete with traditional costumes. She even dragooned me into organizing the kids to perform Catalan folk tunes.

Living her role to the hilt, Marie-Christella inhabited a tiny hermitage apart from the village, acquired a donkey to haul water to it, and wore sandals on bare feet year-round, presumably to symbolize her ascetic lifestyle. The Parisian complained that she was usurping his role as acting mayor, and accused her of being independently wealthy.

Staked alone in her pasture for any length of time, my donkey was pining away. Silent for days, she eventually let loose with a long and loud complaint of heehaws that reverberated through the mountains. I offered to stake the nun’s donkey with my Mitjanit, so that she would have company. In exchange, I had the use of her younger animal for fast trips up the mountain when I started milking ewes stationed to graze the summer pastures.

Afterword

Our séjour in the Eastern Pyrénées lasted nearly seven years and included many adventures that I have not recounted here. Our children continued reading and writing in two languages and performed song and dance in several French folk traditions. René learned to bake cakes and become a soccer star. Larisa learned to tolerate school as a foreigner at the top of her class.We learned a set of low-tech subsistence farming and homesteading skills whose integration into a low input farm design enabled us eventually to make a living at small scale farming later in the US. The memories of living in stone houses with long mountain vistas marked our attempts to build a farmstead on a hilltop in the rolling hills of upstate New York.

Watering the Garrotxes: donkey farming in the French Pyrénées

Karl North February 6, 2024

A region of distinction in decline

French Catalonians commonly call their region Roussillon, but as one ascends from the coastal plain that stretches from the city of Narbonne to the Spanish border, first into the foothills, then into the narrow, steep-sided Tet river valley known as the Conflent, different landscapes take on different names. The last town with shops up the N116 national highway for 20 km. up a mountain gorge is Olette, population 600, where Larisa, my youngest child, received most of her elementary schooling. (Parenthetically, unhappy after her first exposure despite being ranked at the head of her class, Larisa quit school. After taking a year off playing in our mountain village with smaller kids, she reconsidered, and decided to return to her position as sole “étranger” in her class.)

A right turn off to the north from Olette takes one into the valley called Garrotxes, some of which borders on the township of Canaveilles, with its partly abandoned village perched at 3000’ along a ridge overlooking the Tet valley, where our family lived for most of the 1970s. Most of the rugged mountain terrain of the region had been under a variety of more or less intensive management until the end of subsistence farming communities circa 1960. But a decade later after the younger generation had left the mountains seeking an easier life, most of it had rewilded, and the locals called any wild place the garrotxes, which means “ the sticks” in Catalan.

Besides a school and a gendarmerie, Olette sports a restaurant, a café, a tabac, a pharmacy specializing in herbal cures and significantly, two dueling butcher shops. The family budget rarely allowed us to patronize either, even for “boudin”, or blood sausage, the cheapest next to tripe. However, the school sent its pupils to the restaurant, whose menu, created for the summer tourist trade, boasted local stream-grown trout and lamb chops, so my children ate meat daily.

Olette’s other distinctive landmark is its church, really a small cathedral, presumably because it was built to serve a wide region of mountain communities. Like most churches in a long-secularized France, it stood practically empty most days. Its young priest, Joseph, one of the three sons of the Flemish family Reymaakers (sp) who had relocated to the valley of the Garrotxes a generation before, was known locally as the hippy priest, for various reasons. One was his attractive assistant catechism teacher, who was rumored to be his girlfriend. Also, as young urban refugees began to filter in during France’s belated version of US sixties counterculture, Joseph, reduced mostly to circuit riding through the mountains, made several attempts, mostly rebuffed, to help the marginals, as they called themselves, settle in to mountain living. This put the priest in the unenviable position of mediator between the locals and the newcomers, who the remaining locals viewed as urban lightweights who would never last in a terrain so challenging that it had driven out most of their children.

Midnight mass on Christmas eve was one of the few times in a year when the Olette cathedral was packed to the gills, despite competition from the café, which held a rousing, inebriated bingo fest for the anti-clericals, a large population in southern France. Apparently, Joseph had learned that I had been studying classical guitar for several years, and decided to recruit me for a solo performance during the midnight mass. My little Bach prelude was reasonably successful, more because it was such a novelty at the annual midnight mass than for the quality of my playing.