An Outline of Benefits from a Lower Energy Civilization

By Karl North | December 12, 2011

The Premises

The universe ultimately runs on an energy economy, not a market economy as the dominant economic ideology claims. Ecological damage is tied to energy use of any kind in our peculiar type of economy where the operating rules of the system require maximization of profits at any cost. Unrestrained profit maximization in turn impels the conversion of energy and raw materials into garbage as fast as possible.

Moreover, increasing material progress requires technological solutions of increasing complexity, and the more complex the solutions, the more energy they consume. The global economy is an example of a complex solution. Also, more complex solutions need a society to maintain a more costly infrastructure. Hence infrastructure maintenance alone draws increasing energy and raw materials. Finally, increasing friction in the form of various “pollutions” draws off more resources.[1] Ultimately therefore, societies devoted to material progress are faced with diminishing marginal returns.[2]

Persistence of these trends violates laws of nature, causes increasing social instability, and leads inevitably to collapse.

These notes therefore assume the inevitability of a lower energy civilization. How low will it go? What will civilization look like? While accurate prediction is impossible, there are ways to look at the question that provide insights, and can even dispel some visions of ‘gloom and doom’. We know a lot about the way the world looked before the advent of fossil fuels, so we can look at how societies used the available energy late in that period, say 1800 in European civilization and its extensions as a point of departure, and ask, how will the post-petroleum age differ?

First, we can ask: at that level of available energy, how much development of alternative energy is possible? That’s a different question from the way many look at the alternative energy potential today, when relatively rapid development of alternatives like wind and solar still benefit from cheap fossil energy in many ways, including essential industrial, commercial, and communications infrastructures built with cheap oil.

Then we can ask: how much of the new knowledge acquired in the last century or more will make possible a better quality of life than was achieved at the beginning of that period? Access to knowledge will not necessarily mean access to today’s technologies developed from that knowledge. Like energy itself, every technology has life-cycle energy costs, an energy tail if you like, that may no longer be affordable, and includes essential infrastructures that may no longer be possible either. It will be as if every product had an embedded energy content label that will decide its survival potential in the energy descent.

However, this perspective on the energy future augurs a whole new potential growth industry of invention that uses today’s knowledge within the energy constraints of earlier times. Research and development will be about how to use the knowledge behind everything from medicines to metallurgy, but in ways that conform to the new energy and other resource constraints.

One of the immediate benefits of awareness of the energy future is that the aware can use the amazing lingering tools of industrial civilization to prepare for that future. We can use the internet and other tools of the information age, and we can use the concentrated energy of fossil fuels while they are still affordable. And we can use organized power of the industrial economy while it lasts.

In view of the magnitude of the challenge – facing the end of industrial civilization as we know it as well as the difficulties of transition to a post-petroleum future – this essay attempts an inventory of the compensatory benefits of that future, notions that woven into a narrative might make that future more acceptable, and help people accept it and get on with it.

Material Benefits

Before the fossil fuel era, the ecological load that human populations imposed, as measured in raw materials depletion and rates of damage to essential ecosystem functions, were much lower than they are today. Where the environmental movement has achieved little, diminishing access to cheap energy will inevitably begin to offer better solutions to present overshoot of carrying capacity in many problem areas, simply by shrinking the industrial economy, which slows the rate of damage. Effects on some main problem areas are:

- Slower depletion of both nonrenewables and things that are renewable only slowly or at high cost. Recycling will become a necessity, a ‘growth industry’.

- Less chemical pollution of soil, air and water, including greenhouse gas production.

- Serious reduction in human invasion of other species’ niches and the resultant mass extinction of species, as human resource use drops from abnormal levels of the last 200 years, and returns to a carrying capacity that ecosystems developed over millions of years of natural history.

- Diminishing capacity for modern warfare, with its impersonal, long-distance carnage,[3] and for the long-distance institutional violence of modern economic empires.

Social Benefits

- Security.

A. For most of us, the wealth and income that we earn in this economy offer little real security because receiving them confers little direct power over them and their source. As the dominant organization of economic life becomes more brittle and unreliable, its ability to provide economic security declines, and a subsistence perspective will become more attractive to individuals and communities because it offers economic security through more resilient structures. A subsistence perspective is not necessarily a return to a particular historic model of a subsistence economy but something deeper: a view that seeks to regain the economic security and other benefits – mutualism, reciprocity and production for use value not market value – that characterized historic subsistence economies.[4]

B.Besides offering economic security, a subsistence perspective is a view of empowerment that gives priority to the ability to produce or obtain the necessities of life through control over the necessary resource base (land, plant and animal seed stock and their genetic heritage, income from household work, etc.).[5] Hence the adoption of a subsistence perspective has empowerment value. Economic relocalization has the potential to increase economic security by achieving food sovereignty, for example. In the present global economy, growing mangoes empowers few in Nicaragua if the control over the mango plantations and markets lies in the hands of transnational corporations in New York. In fact, Nicaragua suffers distinct disadvantages: the industrial agricultural practices of the TNC destroy soil fertility and pollute the environment, the mangoes do not enter the local food economy because they bring a better price in New York, and the mango plantations displace local food production, weakening food security for Nicaraguans. This is a global pattern in the present system. Hence the advantage to local communities of producing milk in the favorable conditions of New York State’s dairy country is largely lost because milk markets are under corporate monopoly control.

C. When it becomes clear that long-term inflation or its equivalent has been baked into the US financial cake, and that time spent making money that has shrinking value is a treadmill, people will discover the relative advantages of time spent producing the inflation-free goods of subsistence.

2. Social Relations.

A. Societies will need to replace technological solutions with ones based more on human relations. This will stimulate the rebuilding of local community, including the revival of the collectively managed commons[6].

B. As economies return to more local production, gender relations may improve. Compared to modern society, peasant societies often demonstrate more balanced gender relations, since women are often in control of markets despite distinct gender roles in the division of labor.[7

C. In human-scale economies, communities are more aware that economic health increases with equality and its broadened purchasing power. Evidence of this from peasant communities is that merchants vary prices according to a buyer’s ability to pay.[8] The increasing strength of the informal economy at a human scale, including to a degree the gift economy[9], carries its own potential benefits to community social health.

3.Economy.

A. Much that is harmful in the present economy will become too costly to prolong, at least at present levels – the constant advertizing blitzkrieg; the “happy” motoring transportation economy with its traffic, road rage, commuting, and massive inefficiencies; the distance, “colonial” economy that enables centers of wealth and power based on exploitation of hinterlands[10].

B. As happened in the collapse of the Soviet system[11], an informal food economy (theoretically illegal in the former USSR) can put a floor under economic collapse. In much of the world it already does; three quarters of the world’s economic activity is informal economy labor.[12] The informal economy expanded rapidly in the US during the Great Depression.[13]

4. Polity.

A. As the cost of governing at state and national levels becomes unaffordable, social control capacity at those levels may weaken, creating a power vacuum and opening political space for more decentralized power structures, which in turn may allow people more participation in the decisions that affect their lives.

B. As in all periods of instability, the coming one presents an opportunity to break with a long historical period characterized by hierarchical structures of dominance, and experiment with more horizontal structures of decision making.[14] European colonization of the New World offered such a break, and was the site of much social experimentation.

5. Culture and Lifestyles.

A. The more labor intensive agriculture that industrial societies will be forced to adopt will put people into a healthier relation to the rest of nature, and give them a physically and mentally healthier lifestyle, geared to more natural rhythms than the hyperactive ones typical of urban life.

B. The rising relative cost of discretionary consumption may force society toward more satisfying behaviors. Cross-cultural studies provide evidence that happiness and material prosperity are in an inverse relationship.[15] As the market price of frenzied consumerism rises, so that the manufacture of desire is no longer enough to maintain the addiction, other values will have a chance to surface and prevail. And when the energy available can support today’s commercialized spectator culture no longer, people will return to more satisfying, participant forms of cultural activity.

C. Local diversity of all sorts – physical, biological, economic, cultural,etc. – will return to replace the boring monotony that global capitalism has imposed, as localities again become free to display their distinctive characters. This diversity represents appropriate adaptations to local physical realities, and is healthier than the tendency of the current system to fit everything on the planet into the same marketable industrial mold.

In Summary

Benefits of the energy descent are not instantaneous; they appear gradually as we learn to use the opportunities of localization. A view from the Transition Movement:

“All the research I’ve seen, all the thinking I’ve done, and all the people I’ve talked to suggests to me that localisation will do a better job of meeting people’s needs – people will be happier and will live in a more socially cohesive way and more sustainably. Or at least it will encourage all those things… If my intuition about what a resilient community is correct, then what you would hopefully find is that as time goes on, people will be experiencing more and more satisfaction of their needs. They’ll find that their community is providing them with more opportunities to enact those needs and those intrinsic values. They’ll find that they’re experiencing fewer barriers to enacting the intrinsic values and satisfying their needs.”[16]

If Greer is right about his eco-successional theory of collapse[17], there will be breathing room for the transition to take place. In a first era of “scarcity industrialism”, as the limits to growth kick in, the industrial system will work, but less and less reliably, and will provide both time and incentives to evolve adaptive habits and structures of cooperation, localization, self-sufficiency and voluntary simplicity. He argues that the accumulated wealth and power of a century of superpower status will give the US the clout to provide temporary fixes as things fall apart. Even in his subsequent age of “salvage societies”, the immense accumulated built environment of the age of abundance in heavily industrialized nations will serve as a store of useful raw materials, a bonanza unknown to earlier low energy civilizations.

[1] Bardi, Ugo, “Peak Civilization”: The Fall of the Roman Empire.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Klare, Michael T., “The Pentagon vs. Peak Oil”.

[4] Mies, Maria, and Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen, The Subsistence Perspective: Beyond the Globalized Economy. Also a talk by Mies, http://republicart.net/disc/aeas/mies01_en.htm.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ostrom, Elinor, ed., Governing The Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action

[7] Mies, Maria, ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Graeber, David, Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Dreams.

[10] Berry, Wendell, The Unsettling of America.

[11] Orlov, Dmitry, Reinventing Collapse:The Soviet Example and American Prospects. Also “Closing the Collapse Gap”.

[12] Astyk, Sharon, “Elephants: Involuntary Simplicity”

[13] Ibid.

[14] Korten, David C., The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community. Also the interview, “A Defining Moment in History”

[15] Goldberg, Carey, “Materialism is bad for you, studies say”, www.nytimes.com/2006/02/08/health/08iht-snmat.html

[16] Hopkins, Rob, “Does Transition Build Happiness?”

[17] Greer, John Michael, The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World. See also his blog entries, “The Age of Scarcity Industrialism” and “The Age of Salvage Societies”.

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | 2 Comments » |

Implications for Agriculture of Peak Cheap Energy

By Karl North | November 27, 2011

By way of introduction to what I have to say, let me explain the evolution of my thinking. As a farmer for 30 years, I have been an active participant in the movement to develop alternatives to Industrial Agriculture. As you may know, much of the motivation for that movement was a growing awareness of the damage that Industrial Agriculture was doing to the land and to the quality of food. Because the damage was a slow moving disaster, and the productivity of Industrial Ag was high, there has been a sense that there were choices; Industrial Ag did well at cranking out the food, but we were developing healthier methods.

Now, with the advent of peak global production of oil and soon coal and gas, we are faced not so much with choices as with imperatives. They are imperatives because they are not simply a matter of economic or technological debate, but are the result of human use of planetary resources coming up against permanent hard, physical limits. Let me stress that: in my view and in the view of many in the sciences who have a strong grasp of the laws of nature, ultimately there are no economic or technological solutions, although there are ways those efforts can slow things down, kicking the can down the road as it were.

Here are the basic elements of the story: Access to fossil energy has accelerated its depletion and the depletion of most other nonrenewable resources that are essential to modern industrial society; now declining access to fossil energy limits access to most other resources even more because it takes energy to extract and process them. Hence the depletion of fossil fuels imposes the descent of modern society to a much lower energy civilization, and will impose specific, fundamental changes in the way we produce food, changes that most of the alternative agriculture movement has not considered fully. It will finally cause us to take much more seriously the question of what is a sustainable agriculture.

I would like to take a few minutes to summarize the case for these claims, because these issues are so strangely absent from public discourse, and because, more than any other questions, I believe they will affect how we envision a new agriculture.

I said that these issues are “strangely absent from public discourse”; the reason that is strange is that the highest levels of government are completely aware of the situation I will describe. As resource scarcity deepens and translates into food scarcity, military white papers that are available to the public are describing plans for dealing with the resulting increasing social conflict, both within and between nations. A German military document recently released for publication describes the expected social upheaval and ensuing chaos and general insecurity with unusual candor.

What the high command in Western nations is reacting to is a situation where human society, benefiting from a uniquely high quality energy source in fossil fuels, has used them and other nonrenewables with no restraint to the point where their production is beginning to decline while global demand still increases. Oil in particular has allowed a temporary extravaganza in human history that we call industrial civilization. Cheap oil has led to the rapid depletion of all nonrenewables that are critical to this civilization. Because we took the easy oil and other resources first, the decline in production of all these resources will be necessarily steeper than the ascent. The early warning therefore in all cases is longterm rising costs of all production that uses fossil energy or other essential nonrenewables. The price of phosphorus for example, an essential mineral in food production, has risen steeply in recent years, and the world is nearing peak phosphorus production.

In sum, the energy sources that underpin industrial civilization will become permanently scarcer over the next decades, and the material consumption we have become used to over the last two centuries will decline accordingly as a degree of deindustrialization occurs. Industrial Agriculture, which derives over 80% of its energy from oil, will perforce deindustrialize as well, so our task is not so much to bring it down, but to prepare a timely replacement.

For some, none of this is news. Those of you who are familiar with the Limits to Growth project know that forty years ago the authors modeled the likely future scenarios with impressive accuracy. In 1980 William Catton was one of the first to combine the perspectives of social and ecological science in his book, Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change, in which he said that the advent of fossil fuels had led to an unsustainable “phantom carrying capacity” in natural resource use. He called it phantom carrying capacity because it permitted temporary human population levels and, in the West, per capita resource consumption that both took the planetary ecological load far above real carrying capacity, which would become clear once fossil fuels became scarce. Systems ecologists Eugene and Howard Odum, who were instrumental in the emergence of ecology as a scientific discipline in the US, have been writing in the same vein for decades.

All of these early warnings were ignored or angrily rejected by the high priests of business as usual. However, there is now a copious literature that describes our overshoot of planetary carrying capacity and its most likely consequences. This literature can be found both in print and on the alternative knowledge medium provided by the internet, even as the general public remains largely in ignorance or denial. This issue is so important in terms of both personal and global consequences that I strongly encourage everyone to look at the evidence.

What are the consequences of all this for designing a new agriculture? The future we must design for in agriculture will, in the analysis of many of these writers, of necessity have access to little more energy than the farms of 150 years ago, and lack other key resources that we commonly use today. These changes may impose themselves gradually, but sudden temporary complete losses are likely as well, as fragile supply chains dependent on cheap oil break down. In fact the most immediate vulnerability for agriculture is the supply chain of both farm inputs and food outputs that keeps food in grocery stores, which consists of a complex and fragile mix of processing, transportation, financial transactions, and above all communications. Food retailers keep on average only three days of inventory. A single hiccup in the fuel supply chain could cause food to disappear from grocery shelves.

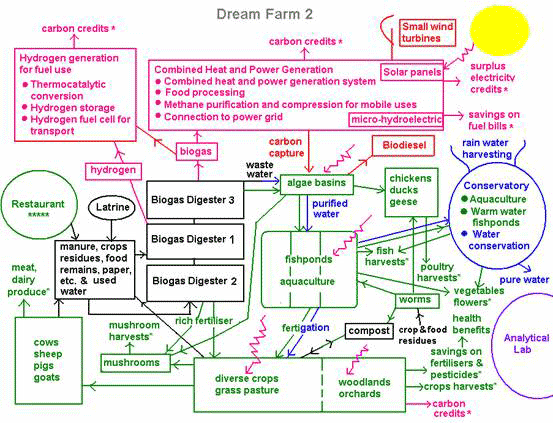

What other adaptations will the new agriculture need to cope with the arrival of humanity at this unique historical tipping point? Most generally, we will need to design farming systems that, like natural ecosystems, are highly input self-sufficient, that utilize the full potential of species diversity on the farm and in the larger ecosystem to provide ecological services to replace external inputs, and are sized and designed in other ways to serve a mainly local human community and food economy. These systems will be knowledge-intensive because they will be highly complex integrated systems. In sum, we must design agroecosystems if we are to continue sufficient food production in the era of energy descent that we are now entering. We talk a sometimes about these goals but could make little progress toward them in the present economy. That will gradually change. In the energy descent economy, much more sustainable farming systems that are not yet competitive will gradually dominate the agricultural economy.

Agroecosystems as I understand the term will differ markedly not only from industrial agriculture but from much of organic agriculture as well. But it is not as if we have to design from whole cloth. Although these systems will inevitably differ from historical models, there are many excellent historical models to learn from that go far toward achieving these design goals. Indeeed, the old integrated general farm with its heavy participation in the local economy was common in the US from colonial times to well into the 20th century in places. At its best it had a number of the necessary internal cycles and species and market relationships.

To design whole agroecosystems, that is, farms that achieve the same level of sustainability as many natural ecosystems, we will need to learn from systems ecology. You won’t find that taught much in agricultural schools. That is why independent research farms, like Hawthorne Valley Farm in New York with its resident scientists and promotion of communication among local farmers, are so important.

I want to end with an example of what we need to learn from systems ecology: it is the importance of what ecologists call Net Primary Production (NPP). NPP is the living organic matter created by photosynthesis and is the entry point in an ecosystem of the solar energy that fuels all other growth in the system. As it is the base of the food chain, the productivity potential of the whole system rests on the quantity and quality of NPP. The same will be true of farms designed as agroecosystems, so from a systems ecology perspective our first design focus should be on the health and productivity of NPP.

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

Gleanings for an Understanding of the Endgame

By Karl North | October 13, 2011

This essay takes as its premise the energy descent future described in an earlier essay, Invisible Ships and Boiling Frogs: The End of Industrial Affluence. As the endgame of this future deepens and the mass media and government remain stubbornly opposed to enlightening the general public, the internet blogosphere has become an excellent alternative knowledge stream. Here, from my perspective, are some of the most effective insights from this literature, recently. For the sake of emphasis, I will categorize them as mental, material, and social questions, although of course they are all interacting.

Mental Issues: The causes and role of denial

Charles Hugh Smith on subtle, unquantifiable, powerful forces at work.

-

- The reliance on propaganda, for instance, has become so pervasive that the notions of truth and honesty have been hollowed out. Nobody expects the President or Ben Bernanke to speak honestly, as the truth would shatter an increasingly fragile status quo. But this reliance on artifice, half-truths and propaganda has a cost; people are losing faith in government, in all levels of authority, and in the Mainstream Media—and for good reason.

- The marketing obsession with instant gratification and self-glorification has led to a culture of what I call permanent adolescence. Politicians who promise a pain-free continuation of the status quo are rewarded by re-election, and those who speak of sacrifice are punished. An unhealthy dependence on the State to organize and fund everything manifests in a peculiar split-personality disorder: people want their entitlement check and their corporate welfare, yet they rail against the State’s increasing power.

These influences seem to combine to shock the public into a state of willful ignorance in the face of the two huge and interlocking crises that represent a tipping point in modern civilization: a) the depletion and gradual end of cheap, nonrenewable resources, bringing the permanent end of the growth economy, and b) the collapse of the capitalist debt economy. Capitalism cannot abide and will not survive the shrinking economy that characterizes the endgame; it requires growth to pay the interest/rent on debt.

Ran Prieur on willful ignorance:

It’s like the famous Twilight Zone episode where there’s a box with a button, and if you push it, you get a million dollars and someone you don’t know dies. We have countless “boxes” that do basically the same thing. Some of them are physical, like cruise missiles or ocean-killing fertilizers, or even junk food where your mouth gets a million dollars and your heart dies. Others are social, like subsidies that make junk food affordable, or the corporation, which by definition does any harm it can get away with that will bring profit to the shareholders. I’m guessing it all started when our mental and physical tools combined to enable positive feedback in personal wealth. Anyway, as soon as you have something that does more harm than good, but that appears to the decision makers to do more good than harm, the decision makers will decide to do more and more of it, and before long you have a whole society built around obvious benefits that do hidden harm.

The kicker is, once we gain from extending our power beyond our seeing and feeling, we have an incentive to repress our seeing and feeling. If child slaves are making your clothing, and you want to keep getting clothing, you either have to not know about them, or know about them and feel good about it. You have to make yourself ignorant or evil.

The first step toward surviving the endgame is to gain an understanding of what is happening, so it is essential to find ways to explain what is happening that overcome willful ignorance or other forms of denial. Two understandings that are paramount now are how the system works and the limits of energy alternatives.

How the system works, over time. In addition to the end-of-growth crisis of capitalism, its core economies (US, Europe, Japan) are experiencing the endgame of a long process of the system’s internal contradictions playing out.

Here is a short and of necessity simplified explanation. The license this system provides to concentrate the economy’s wealth in few hands creates increasing inequality, which reduces the purchasing power of the majority, and regularly sends the economy into recession or even depression. The most powerful capitalist nations can temporarily prevent or soften these cycles through imperial extraction of wealth from other countries and trickle down to the masses through higher wages and cheaper goods. But this process eventually hits limits – for example when the market for big ticket once-in-a-lifetime items like washing machines becomes saturated, or the capitalist class refuses to share more profits with the working class – and the economy stagnates. Then capitalists find they can make more profit by exporting industrial production to the imperial periphery where labor and many raw materials are still cheap. The resulting de-industrialization of the core economies removes the income-producing employment and consumer purchasing power that keeps the core economies running. Again capitalists find a temporary solution by converting their domestic economies from real wealth production to the production and sale of credit. Cheap credit not only revives the consumer economy for a time but also becomes a source of increasing profit to the financial class, which balloons in wealth and power. But a society can absorb only so much debt. Peak credit occurs when the core economies become credit saturated and increasingly hollowed out by consumer, corporate and government debt. At this point, capitalism runs out of solutions to its contradictions, and a terminal crisis of the system occurs. This is where we are today: the endgame of that long historical process.

The limits of energy alternatives. A form of denial that infects much of the environmental movement is a refusal to accept the limited prospects for replacing fossil fuels with anything else, on a societal scale. The fact that individuals can invest in alternatives has led many to falsely assume that alternatives can simply scale up. As John Michael Greer and other students of the question have pointed out, these limited prospects are not a matter of technological debate, but rather a function of hard physical limits, some of which even well educated people have yet to consider. To give one example, the construction and maintenance of wind and solar electricity at a significant scale requires an industrial economic infrastructure of a level that soon the world will no longer have the energy production to maintain. The only reason we have been able to easily erect and run a few massive arrays of wind-electric generators today is that we did it using some of the last cheap oil and the leftover but slowly crumbling industrial base built in the age of cheap oil.

The other problem with significant replacement of fossil fuels is that the alternatives provide the energy to prolong the massive depletion of nonrenewables and use them to maintain the industrial production that is trashing the planet. The Jevons effect says that energy efficiency gains, in a typical capitalist political economy of few policy constraints, are used in ways that lead to higher energy use at the macro level. Something similar is at work if “clean” energy alternatives replace fossil fuels to a significant degree. The use of alternatives (again in our dominant form of political economy) will be used to chew up the same resources as fossil fuels do. Many of these resources are nonrenewable, many of them destructive of global carrying capacity in their production and use. As just one example, fossil fuels have permitted an industrialized form of agriculture that is an ecological slow-moving disaster but has temporarily doubled world population, which in turn is causing its own problems. A systems analyst can appreciate the positive feedbacks involved. So in general, significant production of alternative fuels would continue the disastrous process that is producing ‘peak everything’ both in terms of resource depletion and nest fouling.

Material Issues

A material force that is moving modern economies toward decline and collapse at a faster rate than they built up is the increasing system frictions caused by overshoot of carrying capacity. As systems analyst Ugo Bardi puts it, it’s “the idea that when things start going bad, they tend to go bad fast”. One source of increasing friction is the operating cost of various pollutions, including corruption, wastefulness and depletions on a system driven primarily by private profit that seems geared to turn resources into garbage at an increasing rate. Here is one commentator’s short list of the increasing frictions that will hasten collapse:

1. Wall Street: a vast skimming operation on the productive elements of the economy.

2. Interest: a hidden tax on productive work (as noted yesterday, on the Federal level, interest on the national debt can be seen as a criminal skimming enterprise). Historically known as usury or debt peonage, the right to charge rent on capital has permitted the growth of a vast criminal syndicate dedicated to no socially useful purpose, which the rules of capitalism allow to operate legally and even sanctify.

3. The 40% of our healthcare/sickcare costs that are paper-shuffling, fraud, etc.

4. The vast profits, lawsuits, needless medications and procedures incentivized by our sickcare system

5. The National Security State/global Empire–huge buildings go up in D.C. by the dozens, all filled with unaccountable bureaucrats and contractors

6. Fiefdoms which have captured the machinery of governance: Junk fees and taxes skimmed to support unproductive layers of bureaucracy

7. The military/industrial complex that feeds imperial expansion and control.

8. The prison industry to control the population made useless by increasing inequality

9. Exurbia: the cost of driving out to the big box stores

10. Massive overconsumption, the result of the highly successful manufacture of desire for unnecessary goods and services.

Tainter’s ‘diminishing returns to empire with increasing size and complexity’ appears to capture much the same concept. Civilization has to work harder and harder to get the same results, and like an engine wearing out with increasing friction of moving parts, eventually freezes up. Add energy and other resource depletion, and the result is that the friction dominating the endgame results in a very steep descent.

Political Issues

Waste. Industrial societies have used the two hundred years of fossil energy joyride to generate enormous waste, some of which functions as “frictions” like those listed above. The US is an extreme case, for example with its trillion-dollar-a-year cost of imperial adventures advertised as ‘defense’. From a purely technical standpoint, while some cheap fossil fuels remain we could turn that energy and other resources consumed in this extravagance toward a conversion of the way we produce life’s necessities (food, shelter) and even some of the better things in life (information, transportation, culture) to modes that might help us better survive the energy descent. But the political will is lacking, and it is not a simple matter of regime change, because the general public, by now victim to generations of indoctrination to false notions of how our political economy works, can no longer make useful political decisions.

Conservatives have been persuaded that the problem is government per se, not seeing that this government fails to serve them because, like all governments, it serves the interests of whoever has the most power, and because this government operates in a society where all the wealth and power has been concentrated in few hands. This is a consequence of the very sort and scope of freedom that libertarians worship and most of us have been taught to embrace. Ran Prieur on freedom as no holds barred:

Americans think freedom means no restraint. So I’m free to start a big company and rule ten thousand wage laborers, and if they don’t like it they’re free to go on strike, and I’m free to hire thugs to crack their heads, and they’re free to quit, and I’m free to buy politicians to cut off support for the unemployed, so now they’re free to either starve and die, or accept the job on my terms and use their freedom of speech to impotently complain.

Liberals on the other hand have been persuaded that the system is fundamentally OK, if only we could do some essential repairs, when in reality the very rules of the system have been set to concentrate wealth and power in an oligarchy, to which any form of government, no matter how reworked, will on the whole become subservient. So any sustainable alternative must operate by fundamentally different rules.

The state of political collective consciousness described above does not seem amenable to rapid change.

“System change, not climate change” – activist slogan at Copenhagen Climate Conference.

“Climate change is only a symptom of a profit-maximizing market system gone wild. We need to change the root cause, the system itself.” – Naomi Klein

Quality of Life. The idea that the transition to a lower energy society, the one we inevitably face, must be a sudden, unmitigated disaster is false. Much of our society lived well at the energy consumption level of a century ago, before oil became central to our present material standard of living. US society uses 4-6 times more energy than the rest of the world, without any gain in quality of life. Europeans use half the energy we do; my experience living a number of years in Europe is that their quality of life is generally better than ours. Brazilians use one eighth of the energy we use, and their quality of life, based on the Human Development Index (life expectancy, educational level, relative income) is nearly the same as ours. As Nicole Foss stresses, happiness is related to level of expectations, so we simply need to lower ours.

Given the ecological damage that the planet has sustained in the last century, even a late 19th century standard of living is not likely to prove sustainable in the long run. But in the short to medium run the proper use of presently wasted resources could provide the slack needed to adapt to lower expectations, making of the transition period a slow-moving disaster rather than a sudden one. However, such a systematic, nation-wide change in economic priorities would require the conversion to the equivalent of a war-time command economy, a major paradigm shift in a nation indoctrinated to free-market ideology.

Thomas Kuhn famously observed that paradigm shifts happen not when the investors in the old paradigm change their minds, but when they die. – Ran Prieur

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | 5 Comments » |

The Case for a Disorderly Energy Descent

By Karl North | May 20, 2011

The energy descent from peak oil production imposes decades of contraction in the global economy. An orderly contraction, particularly in the US, is not likely for a number of reasons. This is a summary of the case for a disorderly descent, garnered from many sources, a couple of which are listed at the end of the essay.

One reason has to do with the nature of the oil extraction and processing industry. According to industry experts, once existing oil wells are shut down, the costs of restarting production are high. The same is true for refinery shut-downs. Also, refineries cannot be economically run at less than capacity. Finally, oil exploration is an increasingly costly and lengthy process. These supply chain problems magnify oil price volatility as it interacts with global economic contraction, thereby punctuating economic behavior with ever deeper stall-outs.

Other reasons derive from the nature of modern industrial society and its world-economic system. First, debt-based economies cannot shrink slowly. Because of the need for an economy to grow to pay interest on debt, when growth is no longer possible credit tends to dry up, the investment needed to merely maintain an economy in operation begins to fail, and the economy experiences periods of paralysis as critical pieces break down. As one analyst put it, capitalism is not designed to run backwards.

Perhaps the most important risk is to the number of supply chain functions required to keep modern economies operational[1]. As infrastructures are not maintained, the just-in-time inventory typical of modern economies is disrupted, with ripple effects throughout the system. Gas lines at filling stations prevent a suburbanized labor force from getting to work. Grocery shelves lie empty for extended periods. Deeply off-shored economies like the US suffer most from supply chain disruptions, and have no rapid recourse to re-industrialization.

Ultimately, cultural conditioning may be the strongest disorder-generating influence[2]. The widespread denial that the pattern of civilization of at least the past two centuries is unsustainable leads to political paralysis, as eminent writers and powerful interests continue to argue for unlimited growth, and the general public, having lost most skills of self-sufficiency, sees no hope in alternatives to its current lifestyle.

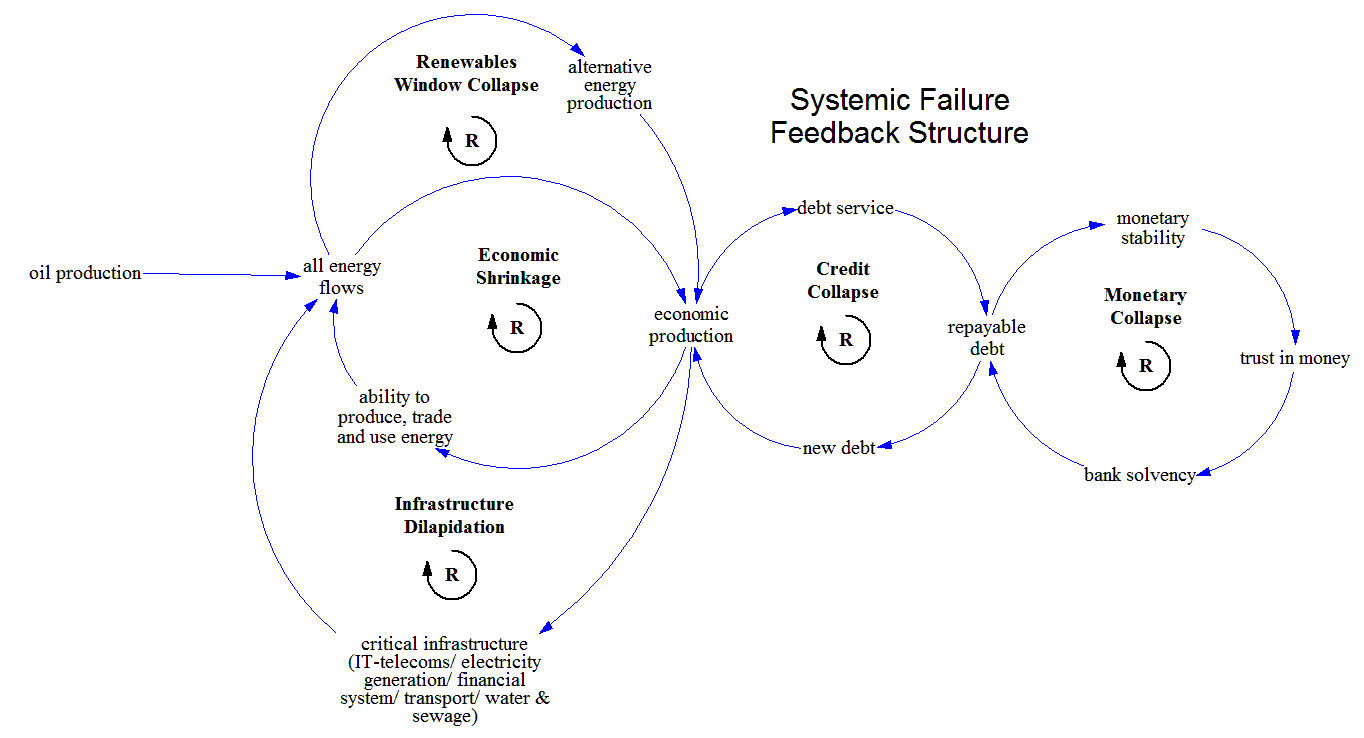

No one can predict exactly how a disorderly descent will unfold. One reason is our inability to foresee historical contingencies like natural disasters, and resource wars and other social upheavals, which could accelerate change in societies that are already at a tipping point. Second, assuming the importance of the factors previously described, we still can’t predict exactly how they will interact. But we can develop a dynamic structural model of the interdependency of those and other important variables, a causal structure that captures important feedback effects, and thereby provides insights into likely scenarios. Here is my model of that feedback structure, gleaned from the now prodigious literature on the collapse of modern society that has begun to occur. As you can see, it suggests the likelihood of cascading effects, or falling dominoes as it were, provoked by the new era of permanent decline in global oil production (Readers who seek help in reading the causal loop diagrams in this essay are directed to my introduction to systems thinking).

As many students of the energy descent have pointed out, the effect of Economic Shrinkage, the first domino to fall, is to cause demand destruction, which makes oil temporarily cheaper, and grants a brief pause in the economic decline. So the early shocks in the energy descent may not cause a full cascade into Credit Collapse and eventually Monetary Collapse. However, initial economic shrinkage increasingly hampers alternative energy production and infrastructure maintenance, which in turn accelerate economic decline. Because all the feedbacks in this model are reinforcing (R) loops that accelerate change, a cascade, once started could trigger deep steps in the stairway of collapse.

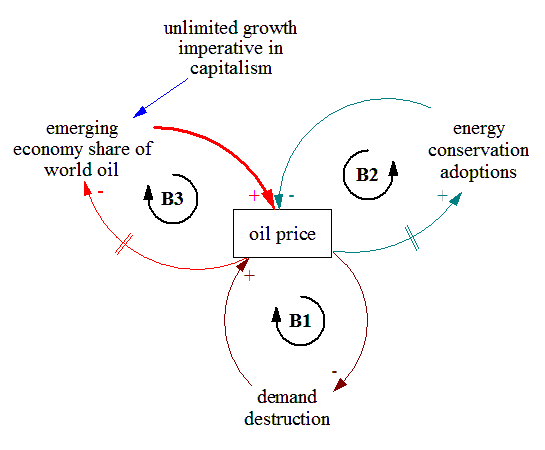

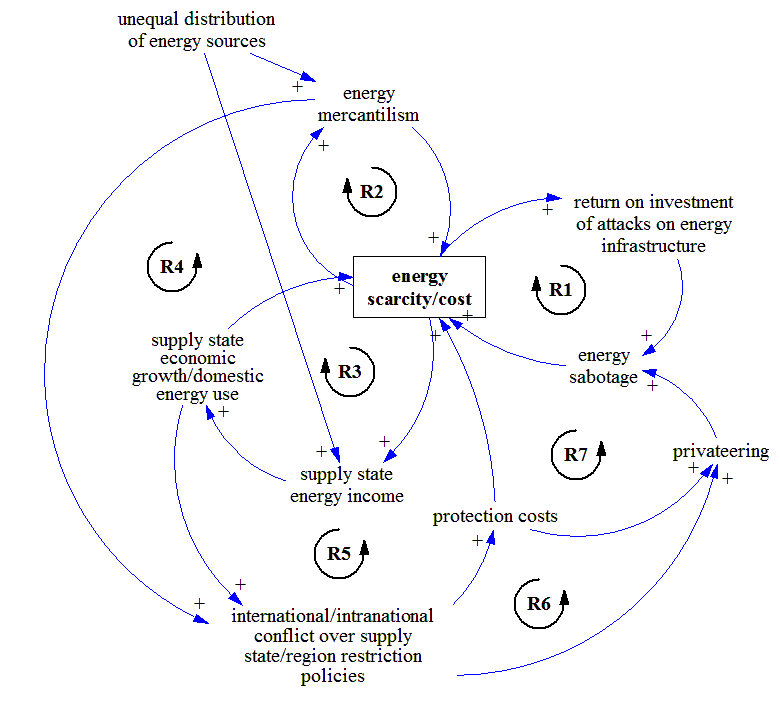

Because the dynamics of oil production itself and its price/scarcity are central to understanding the socio-economic consequences of the energy descent, it is important to model the feedback structures that govern those. The attempt below is separated into two models to facilitate analysis, one containing negative, balancing feedbacks (B) that slow or counteract the expected rise in the price/scarcity of oil, and the other hopefully capturing the main positive feedbacks (R) that could accelerate oil scarcity.

Geopolitical Feedback Structure of Declining Oil Production: Feedback Effects on Short to Medium Term Oil Prices After Peak Oil

Negative Feedbacks

Positive Feedbacks

What follows is a brief analysis of how global trends in key variables are liable to create a ‘disorderly oil market’ as the oil era ends. It is intended to complement the explanation of feedback provided in the graphic models.

The era of cheap oil saw the emergence of complex and ultimately fragile social and economic structures. During this time for example, the spatial distance between material and labor resources, production facilities and markets could expand with few obstacles. As this distance economy becomes increasingly costly and eventually unaffordable, perhaps the strongest feedback effect exerting short term downward pressure on oil prices is the specter of a widespread economic depression triggered by a chain reaction of non-performing mortgage and other debt leading to bank and insurance industry collapse, etc. This is the wild card that I represented separately in the first diagram, Systemic Failure Feedback Structure, because its tipping point is much harder to estimate – when it might kick in and possibly overwhelm the other feedbacks.

By contrast, a number of the negative and positive feedback effects on the global oil economy, which I described and diagrammed above, can be expected to occur in the short to medium term. However, the oil price ‘disorder’ that these feedbacks will generate only puts off the arrival in the longer term of a lower energy civilization (here assumed to be inevitable), with the catastrophic changes that implies. In the relatively short run these changes could include severe suffering, particularly for non-peasant populations heavily dependent on the distance economy of the industrialized world and addicted to its material comforts. However, in the longer run the change to a low energy civilization also holds the potential to include major benefits: a return to a more sustainable pattern of resource use, healthier, happier lifestyles as people are released from the propaganda grip of the consumer economy, and liberation from wage slavery and the constant damage to quality of life from distant decision makers as the power of monopoly capital over the decisions that affect our lives goes into decline.

Here is how the negative feedbacks work:

A shrinking buyer market

This is the ‘isolated islands of prosperity amid demand destruction’ scenario: more and more of the global majority is priced out of the market for all products affected by rising oil price. This is happening already to many populations of the global south. But a shrinking buyer market eventually puts downward pressure on oil price, at least for a while, as in the feedback loop B1. Depending on the comparative strength of this feedback loop, it will manifest as either a brake or temporary reversal of the generally upward trend in the global oil price.

Alternative Energy and Energy Conservation Adoptions

Existing technology can rapidly reduce fossil fuel use, notably in transport and heating, particularly in the US, where such changes will be most affordable, at least in the short term. For example, an expected response in the automotive market to rising motor fuel costs will be an eventual rise in fuel efficiency. When the average US car gets 40 mpg it will more than halve the current U.S. need for automotive fuel and depress oil prices significantly for a while, as in feedback loop B2. More than the shrinking buyer market, this feedback loop involves significant delays (marked as // in the diagram), as consumers react slowly to rising prices in the affected oil products. If delays are too long, however, both consumers and producers become caught in a poverty trap that closes off the window of opportunity to adopt energy conservation technologies. The way this works is that rising oil prices render unaffordable the technologies, whose production still depends on fossil fuel use.

The momentum of economic growth in the global capitalist economy

Analysis of the political economy of capitalism has long demonstrated that its characteristic structure and decision rules generate an historically typical behavior: a drive for unlimited growth, provoked in turn by the need to accumulate capital to compete in a global economy shaped by unrestrained use of private capital. In the era after peak oil, this drive will manifest itself where opportunity offers, e.g., in emerging economies with access to masses of cheap labor, like China and India, and to a lesser extent everywhere that lucrative investment opportunity emerges. In the short to medium term this includes such fuel use as caused by a continuing trend toward exurbanization in developed economies. Eventually rising oil price will put an end to unlimited growth, which will then depress oil price, as in feedback loop B3. But due to delays in stemming the growth drive, the loop will be weak in the short term. In that period the momentum of the growth habit of capitalism will act to push oil prices higher.

The positive feedbacks illustrated in the second diagram complicate the picture even more, and would require extended analysis that is beyond the scope of this essay. As the diagram shows, they are numerous and interlocking, and therefore have the potential to cause rapid rises in oil price and/or scarcity. Some of the effects are already happening. The recent Russian decision to halt oil exports could be an example of energy mercantilism R2 or perhaps the need for domestic use of domestic oil production R3. The decision of Iraq to sell its oil for Euros not dollars is an example of mercantilism R2 that allegedly provoked the second Gulf war. That conflict with its sabotage and other damage to Iraqi oil production is an example of R4.

Conclusion

The timing and time span of the feedback effects described above is impossible to predict due to the complexity of their interaction (that is, which loops become dominant when) and to the likelihood of unpredictable triggering events such as the likely global economic depression. Thus the disorderliness of oil prices in the short and possibly medium term (20 year time horizon), and the damping effects of the feedbacks on oil price rise at times during the period, are the only safe predictions possible from this analysis. At the same time all three of these dynamic models suggest probable future scenarios that we would do well to take seriously.

[1] Korowicz, David. 2010. Tipping Point: Near-Term Implications of a Peak in Global Oil Production. Feasta Foundation. March 2010.

[2] Catton, William R., Jr. 1994. “The Problem of Denial” http://www.mnforsustain.org/catton_problem_of_denial.htm

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Recent Additions, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Systems Thinking Tools, Uncategorized | 4 Comments » |

What Every Marxist Needs to Know about Ecology

By Karl North | December 12, 2010

Karl North 2010

The problem and some options

Nature rules. Everything we do that violates the rules of nature will eventually fail. Nature’s rules include broad ones like the laws of thermodynamics, and more specific ones like those that govern how the soil food web feeds plants.

It follows from the laws of thermodynamics that there are limits to growth. The dialectic of evolving capitalism has brought the planet to the point where the limits to growth are kicking in. Human civilization is at a turning point: to feed over-consumption in the industrialized world and overpopulation in the rest, we are rapidly depleting finite resources, exceeding sustainable harvest of renewables and damaging essential ecosystem processes. Human consumption has overshot planetary carrying capacity by about a third. This overshoot has gone on long enough that it is rapidly eroding planetary carrying capacity itself. This happens to every species that goes into overshoot. It’s a rule of nature. It’s taken for granted in systems ecology. Yet even people who recognize this persist in advocating alternatives to capitalism that include economic growth.

We have no choice: if we do not advocate and begin to create zero growth political economies, nature will force them on us. However, there are different options in this direction. One is for industrialized societies to consume much less so that the imperial periphery societies could consume more. This would work regarding the consumption of renewables like soil, water and forest if it reduced imperial consumption and plunder of such resources in the periphery well below the refresh rate, so that societies in the global south could, with appropriate policies, partake of them in ways that stay within sustainable harvest rates. This would not work with finite resources like fossil energy and strategic minerals, for no matter who uses them, without perfect recycling they will continue to deplete until too scarce and costly to use for most purposes. As Marxists are well aware, the implementation of a major transfer of control over resources that this option implies would involve revolutionary national and class warfare. This is not an decision to be undertaken lightly, and few existent revolutionary movements are prepared to carry it through in the near future to a successful conclusion.

Another option has more potential right now within the currently evolving structure of global power, and can profit from the gradual weakening of the old industrial centers as power shifts to emerging ones. In local communities where resource consumption is still relatively low and capitalist indoctrination toward its standard of material consumption is still weak – and this is true in much of the rural global south – strategic reallocation of resource use could replace growth policies with policies designed to occur within a zero growth political economy, and still vastly improve quality of life. But unlike virtually all current projects of national socialist revolution, it will require awareness that ‘progress’ in the sense of development toward Western levels of material consumption is no longer a meaningful, or in the long run attainable goal. This option still requires strong resistance to imperial control, but because it would be localized and the stakes in many cases would be lower, imperial efforts to put down these ‘resource liberation movements’ as they proliferate in many localities around the world will be of lower priority for the old imperial centers that are now facing more serious problems as they decline.

The greatest potential for implementing this option exists in client nations of empire that are descending into a chaotic state that Marxist James Petrus describes as lumpen capitalism. Mexico and Colombia are examples. Potential models for this option might be the Zapatista Caracole movement, the landless worker movement in Brazil, or rural insurgencies in Afghanistan, the Philippines, Colombia and elsewhere that have gained control of territory and its renewable resources. If movements like these can create revolutionary development policy goals that respect ecological imperatives and the resource constraints of today’s planet, there is good reason to believe they can achieve egalitarian and quality of life goals that socialists have always desired of the revolutionary process.

The Laws of Nature

The rest of this essay will attempt to describe and help fill the gaps in anti-capitalist thinking about ecological economy, its laws and imperatives and their implications for developing a “dialectics of nature” (Engels’ phrase).

What are the laws of nature that social scientists and activists must respect? How will they affect our understanding of social dynamics? What should a historical materialism that includes both society and the rest of nature in its analysis look like?

The early US pioneers in ecology, Eugene and Howard Odum, developed dynamical models and methods that are fundamentally similar to Marxist dialectical models, to show how structures of causal relations explain behavior and evolution in both natural and humanly managed ecosystems. These models subsumed the laws of nature. Limiting not only growth but also sustainability of all systems are the laws of thermodynamics: no energy can be created, and everything is subject to entropy. Things fall apart, energy is lost in all activity, and energy inflow is constantly needed simply to maintain systems in operation. As applied to all species including humanity, growth or even survival depends on the energy flow available to the system, and can increase only until the ecological load – the use of resources and essential ecological services – reaches carrying capacity, the maximum sustainable ecological load. Prolonged overshoot of carrying capacity leads to its erosion and ultimately to the collapse of populations or their material standard of living, or both. The Odums were well aware that these laws and ecological imperatives apply as much to human society as to other species.

As applied to the present human condition, these laws and mode of analysis reveal a planetary society well into overshoot and erosion of carrying capacity. William Catton, one of the first ecologically informed scientists to point this out, wrote in 1982 that we are living the last decades of an “age of exuberance” made possible by the temporary boost in carrying capacity that fossil energy grants. This “phantom carrying capacity” permitted accelerated population growth in the global south and per capita resource use many times the world average in industrialized societies, whose only possible final outcome is decline – the classic overshoot and collapse that threatens all systems that exceed maximum indefinitely supportable ecological load.[1] Just to keep industrial civilization going, even with no growth, requires enormous energy inputs, which eventually will be available no longer.

How does this perspective alter our analysis of capitalist dynamics? The irony is that while Marxists have excelled at exposing the internal economic and social contradictions of capitalism, which have yet to bring down the system, what will actually bring down the system, at least in its current globalized and highly industrialized form, is a much greater contradiction that is looming: between an economic system that requires growth to survive and the external material reality of the limits to growth. Until now, the capitalist system has been able to escape its internal contradictions through militarization, exportation of industry, financialization and other gambits. But its supreme safety valve has been the planetary niches that remained to invade and pillage of their land, minerals and cheap labor. Like the American frontier a century ago, this safety valve is now closing.

Capitalism is now coming up against nature’s laws that, unlike revolutionary movements, never fail. Mother Nature always bats last. Unfortunately, generations of cheap energy have shaped industrial economies and cultural values in ways that make them extremely fragile yet highly resistant to easy change. Capitalism, which must grow or collapse because it runs on the monetization of debt, now confronts a future of declining energy, which brings not just stagnation but decades of global economic shrinkage until a bottom is reached where humanity has adapted to a lower energy society. Not just capitalism, but humanity is at a major turning point in the dialectic of natural history.

In the face of these prospects, Marxists have an opportunity, not yet fully embraced, to help dismantle the failed paradigm of growth by advocating structural changes, but in the context of conversion to lower energy, no-growth post-capitalist political economies. There is no reason why growth is necessary in order to shift resource allocation from the export-driven pattern in client states of the empire to one that builds an equitable domestic economy anywhere in the world. Why leave such advocacy to the Herman Dalys and the Lester Browns, who have a much poorer understanding of the political economy of the capitalist system?

Critics have characterized steady state economics as a return to static equilibrium models that justify business as usual. They misunderstand that, following Darwin, social ecologists assume not only dynamic equilibrium but also evolution, within the constraints of the biophysical resource base.

Much time has been wasted trying to build justification for an ecological Marxism by searching the works of Marx and Engels for ecological gleanings. This is unnecessary. The seminal works of systems ecology (Odum et al.) are fully compatible with a Marxism that acknowledges its materialist basis. Such a shift would be in line with the original materialist thrust of the thinking of Marx and Engels. We need to remember and take to heart that it was Marx who said that capital exploits not only the tiller of the soil, but the soil itself. But we need to add that endlessly exploited soil (Marx’s metaphor for the natural resource base) will bring down any economy, no matter how egalitarian.

This shift in direction would gain Marxism a wider audience among those who currently see it promoting essentially the same dead-end growth paradigm as mainstream economics in an era of sharply depleting, finite natural resources, especially oil.

For Marx, human economies are in the last analysis dependent for survival on the existence of material conditions of production. The perception that today the depletion and deterioration of these conditions has reached a global tipping point has a rigorous conceptual basis in ecological science in the law of carrying capacity and its erosion through overshoot which, carried on long enough leads inevitably to collapse. Ecologists have documented this process repeatedly for many species. The human species is not immune to this law. In our world of finite conditions of production, economies of any kind predicated on growth will eventually fail.

[1] Catton, William R. Jr. 1982. Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. University of Chicago Press.

Topics: Political and Economic Organization, Recent Additions, Social Futures, Peak Oil, Relocalization, Uncategorized | No Comments » |

On Invasives

By Karl North | November 18, 2010

What I will say here about the issue of invasives may seem picky, but it is not, because it points up a fundamental flaw in how we think about any intervention into the complex, systemic world in which we live.

The flaw running through the whole discourse about invasives is the tendency to see them too simply, and, in particular, in too short a time frame. In the longer, holistic view, all species are historically invasives, including humans. As my current bumper sticker says in protest against the wall at the US/Mexican border, “We are all resident aliens”. In fact, any innovation or other intervention in a complex system (like an organic farmer buying a Kubota tractor) is initially an invasive.

It is true that, driven by temporary fossil energy, accelerated social change has in turn accelerated the spread of species into new environments. But to approach the issue holistically we need to ask: What is it about the invasive that is counterproductive? Often it is not a quality inherent in the “invasive”, but how fast the system is forced to adapt. If the ecosystem (or its management team) has time to adapt, to develop counterbalancing forces, a new entry may not destabilize it, and may contribute positive functions in the sense of moving the whole toward our management goals. We also need to ask: What are the ripple effects of the invasion or intervention – how the system is affected in multiple ways over time? Are there ways to adapt the whole so that benefits outweigh costs?

For example. Rats are usually seen as an unmitigated evil invasive that, at their worst brought the plagues that decimated the urban societies of medieval Europe. But the rat population on my farm is kept under control by farm dogs and barn cats. The dogs and cats provide other positive services on the farm, and the rats support the dog and cat population by adding essential animal protein to their diets. So, are the rats really “invasives”?

To generalize, if the intervention involves a new species (as opposed to a new technology) we can sometimes apply nature’s management tools to maintain system dynamic equilibrium. One is to make sure a predator species population is sufficient to control the new species population. Another is to populate the ecological niche of the new species with a competitor species, with the same effect of population control of the new species.

The ultimate take home lesson of this essay is that whether to deal with an unintended “invasion” or a deliberate intervention or technological “innovation”, a system manager to ask the same holistic questions: What are the consequences over time, in the long term and in other parts of the system? Do “solutions” address root causes that are often structural, or mainly symptoms? And the classic, crucial, sociological question: cui bono – who ultimately benefits most?

Topics: Agriculture, Northland Sheep Dairy, Systems Thinking Tools | No Comments » |

Visioning County Food Production – Part Five

By Karl North | October 24, 2010

Part Five: Peri-urban Agriculture

This series of articles is an exploration of designs for agriculture in Tompkins County to approach sustainability in a future of declining access to the cheap energy and other inputs on which our industrialized food system relies. In earlier parts of this series, I proposed principles of agroecosystem design; addressed the key issues of fertility, energy, water, and pest control; and pictured the future county food system as a whole, including its historical context, implications, and the interdependencies among the parts that will make them most effective as an integrated system. I said that providing for the local food needs of urban populations requires a design that integrates three overlapping categories of production systems: urban agriculture systems (many small islands of gardening in the city center), peri-urban agriculture (larger production areas on the immediate periphery), and rural agriculture (feeder farms associated with village-size population clusters in the hinterland of the city but close enough to be satellite hamlets).

In this month’s article I will consider the needs and resources that will shape the design of peri-urban agriculture systems around the city of Ithaca, and offer a case study as a design example.

Figure 1. Cooperative farms on the edge of Havana, Cuba.

Cities are often ringed with suburbs, parks, and industrial and commercial zones that can be converted to larger, more integrated agricultural systems than densely populated urban neighborhoods (Figure 1). Deer and rodents have proliferated in the urban-suburban boundaries that are excellent edge habitats for these species. Agriculture in these areas will need to achieve deer and rodent control by fencing that is effective against jumping and burrowing and by regulated trapping for meat and hides to eventually reduce populations.

The best candidates for conversion to farming are sites that have good soil and water resources yet are close enough for easy access by urban consumers and potential farm labor. Two such areas on the periphery of Ithaca are the flood plain beside the lake and inlet and the nearest locations on the main existing transport routes, particularly those with existing rail lines, north up the east edge of the lake and south along route 13.

The flood plain

One-sixth of 19th-century Paris was devoted to intensive urban gardens, prominently in the Marais (wetland) on the right bank of the Seine River. Fueled by manure from the city’s thousands of working horses, peri-urban gardens fed Parisians with greens, vegetables, and fruits the year around. The history of a similar district on the edge of climatically similar Ithaca indicates its food production potential. This neighborhood was once home to a distinctive waterside community of fisher-farmers who, despite their lower socio-economic status compared to some Ithacans, were able to achieve relative self-sufficiency on the rich alluvial soils and aquatic resources of their neighborhood.

Ithaca has a unique resource in these lakeside and inlet soils. They are potentially the most productive agricultural land in the county when converted to the chinampa-style systems described in Part Two (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mexico City chinampas

Some of this land may now be ”brown fields” of soils that are polluted from years of commercial and industrial use but can be reclaimed biologically. Bioremediation can take various forms. Several years of intensive grazing and repeated trash plowing and replanting of grass cover not only builds soil organic matter rapidly but cleanses it as well by bacterial action as the soils become more biologically active. Instead of normal plowing that buries sod, trash plowing upends it for fast aerobic decomposition. If this is insufficient, raised beds with imported soil are a solution that has worked in many urban locations.

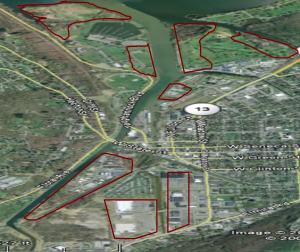

Land use policy for the district would have to change to reflect the food production priorities of the energy descent. Some lands now dedicated to industry, the commercial strip of big box stores, and parts of parks and the golf course will be acknowledged as prime farmland. Figure 3 illustrates examples of potential waterside farm sites.

Figure 3. Examples of potential waterside farm sites on the edge of Ithaca

The politics of conversion of water-side lands to prime food production sites will require a new mindset. Agriculture may be the best use of some of the land now devoted to recreational activities like sailing, picnicking, and golf. Consumers accustomed to shopping in national chain stores will need to learn that they represent what Wendell Berry in The Unsettling of America called an extractive, colonial economy. This economy transfers wealth to metropolitan centers of power from rural peripheries and operates at many scales, from impoverished banana republics like Nicaragua, to shrunken agricultural towns in Nebraska, to the depressed areas of upstate New York. Thus the national chain stores that ring the Ithaca periphery are economic “monocultures” that strip economic wealth from the county just as agricultural monocultures drain fertility from the soil.

Transport route locations

Conversion to more sustainable food production requires more people living closer to food production in order to provide labor and to facilitate nutrient recycling. Energy descent writer Richard Heinberg estimates the need for 50 million farmers in the U.S., up from 2 million today[1]. In a similar assessment, Swedish systems ecologist Folke Günther estimates that the rural farming population needed to support an urban community should be 12 times the urban population. The starting point in our case is a county population of 100,000, of which 30,000 is urban. To achieve the necessary balance, Günther suggests relocation of some urban and close suburban populations to clustered housing in satellite farming villages[2] as older urban housing is replaced by urban gardens. The most economical location for some of these peripheral ecovillages might be in the peri-urban agricultural district along the main transport routes near the city.

Ideally this process would be part of a general physical redesign of both the urban and hinterland communities according to the model that emerged in Europe, where centuries of higher population densities have dictated more careful land use planning. Even today, European towns large and small are characteristically dense clusters of buildings that end abruptly in agrarian vistas.

Visioning a peri-urban case: Waterside Gardens

Commercial strips and malls that typify the urban edge, vacated in the shrinking national economy, are prime candidates for a public takeover that would convert their parking lots to agriculture and the empty buildings to farming and related community uses. To exemplify this conversion, we will envision a farm operated as a commercial cooperative, using a future abandoned Wegmans waterside parking lot and supermarket building (one of the locations outlined in Figure 3). Let’s call our imaginary cooperative “Waterside Gardens.”

A policy framework. The dirty little secret of small farms is that they don’t make much of a profit in competition with industrialized agriculture. A food policy framework guarantees the economic viability of Waterside Gardens:

- As part of a county-wide green belt policy to stop and convert urban sprawl, the city has remunicipalized most of the inlet area from the lake front to Buttermilk Falls, providing a free lease to co-ops like this one as long as they continue to build food security and food sovereignty in the county.

- In the wake of widespread demand for local food sovereignty, the country has revised the Constitution. As part of a growing reliance on local, county-wide economic policy making, a tariff is now levied on food coming into the county based on food miles and the ability of local agriculture to provide the product.

- A trolley stop on the public light rail line serves the site to bring agricultural inputs to the co-op and consumers to its retail food market.

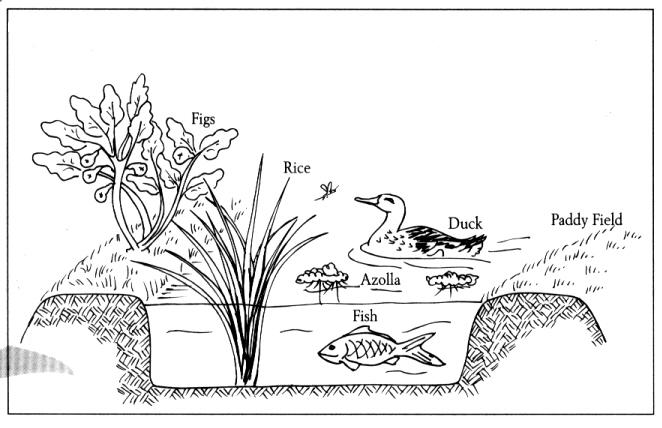

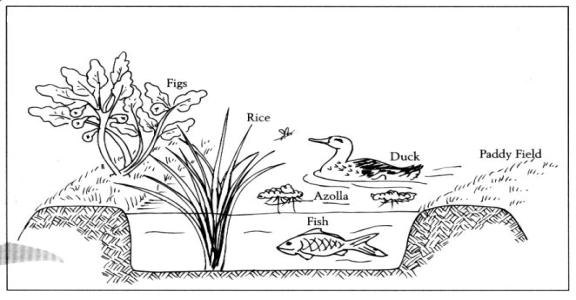

Models of ecological health and productivity. Waterside Gardens (Figure 5) incorporates two highly productive models of small-scale agriculture that have proved themselves to be effective historically in peri-urban agriculture: chinampa-style canal-side gardens (Mexico city)[3] and the French intensive market garden (Paris)[4].

Figure 5. Waterside Gardens (artist’s conception by Jane North)

In the gardens that use the inlet directly, hydrologically controlled subcanals between garden beds divert water from the adjacent inlet canal. These alternating strips of water and land crops are managed to make the system highly productive in several ways:

- Constant sub-irrigation of the growing beds;

- Aquaculture production from a self-feeding, integrated system of water plants and animals;

- Surplus fertility from the aquatic system in the form of muck dredged periodically from the canals for the adjacent bed soils;

- Temperature stabilization from the waterways that improves daily crop growth and extends the growing season.

Farther from the water lie the frame and cloche beds characteristic of the French intensive method. Despite the development of biomass-based plastics, competition from higher priority biomass uses like food and heat has prompted a return to the French tradition of glass for frame covers and the bell-shaped cloches that create the microclimates to protect beds and individual plants.

Windmills pump canal water into raised tanks to provide a constant reserve of gravity-fed irrigation water. Adjacent ponds capture and biocleanse storm water that runs off the city’s hills, constituting a water reserve that makes the system resilient to drought.

Another input essential to the intensive method is a constant and copious supply of fresh manure that is placed under and around frames and cloches to maintain growing temperatures in these all-season gardens. Initially the only manure source was the small population of livestock that peri-urban production systems can integrate. However, diminishing supplies of fossil fuel and limited supplies of local fuels like biogas from municipal black water processing have driven local transportation partially to rely on animal power. A growing mule population now transports people and produce around the county, much of it efficiently on the rebuilt light rail network. Like other peri-urban farms, this one provides stables for some of the mule contingent in return for the steady supply of hot manure. Their hay is transported by water directly into docks at the garden site from farms around the lake.

Wind protection is part of the intensive gardening system. The old supermarket and the high hedges on the northeast and northwest edges stop the coldest prevailing winds, and low walls throughout the gardens reduce wind at plant level while letting in sun.

While much of the French system is possible in urban agriculture, peri-urban spaces allow its full development as it originally functioned on the outskirts of Paris. This is because its year-round production requires quantities of hot manure as well as the constant attention of full-time gardeners highly skilled in the careful timing of watering, frame and cloche ventilation, and protection of frames from sun and cold. This garden recaptures the full knowledge- and management-intensive qualities that made the Paris market garden system so successful.

A more extensive system. The co-op includes a third, more extensive gardening system to grow crops like roots and tubers that need more space and to integrate small animal production. To fertilize this garden, the co-op manages a facility in which pig turners enhance the vermicomposting of part of the city’s segregated organic waste stream.

Originally judged a brownfield, the soil of this part of the market garden spent its first years of conversion to agricultural quality under intensive grazing alternated with heavy applications of compost seeded with fast growing forages in the cleansing process described earlier. Now it consists of beds long enough to be worked by some of the mules housed in the co-op and grassed alleys wide enough to permit farm vehicles and grazing with rabbits and poultry in movable pens, as illustrated in Figure 4. In season, the rabbits thrive on an all-grass diet, and feed for the poultry is supplemented with part of the garbage and worms from compost production. The alleys are lined with composting sheds to which the poultry have access as their grazing pens are moved along the alleys. In all seasons the pigs, poultry, and rabbits consume the co-op’s garden waste as one of their roles in the system.

|

|

Figure 4. Grass-fed rabbit production at Northland Sheep Dairy,a farm near Tompkins County

The old supermarket now serves many new functions. In addition to the stables, it houses farm tools and machines and harvest and feed storage areas. It also includes community centers to market products from adjacent community gardens, train new farmers, and house full-time farm workers and food processing centers. The south front is a passive solar greenhouse that heats the building and grows vegetable and nursery transplants for the rest of the farm.